When he began his term as chief of the Alaminos Motor Vehicle Inspection Center (MVIC) in 2014, a malfunctioning equipment welcomed Dyonn Dacpano at his new office in Laguna.

His office is supposed to test a public utility vehicle’s roadworthiness in Region IV-A using state-of-the-art motor vehicle inspection system (MVIS).

Instead, the brake tester on the right lane where jeepneys are tested has stopped working. It took months before the supplier was able to fix it because parts needed to be ordered abroad. The following year, the light tester became faulty.

It became a cycle; an apparatus would get fixed then shortly after, another would bog down. At one point, the wirings connecting the testers to its monitors corroded because rats gnawed at them.

Last year, all the apparatus have broken down, save for the smoke emission tester and a portable weighing scale, said Dacpano.

“So yun lang ginagamit namin sa ngayon…parang balik kami sa dati, nung walang gamit. Visual na lang (So that’s all we’re using now, we’re back to how it was when we had no equipment. We just rely on visual inspection),” Dacpano said.

Alaminos MVIC Chief Dyonn Dacpano signs off on the MVIS reports of examined vehicles.

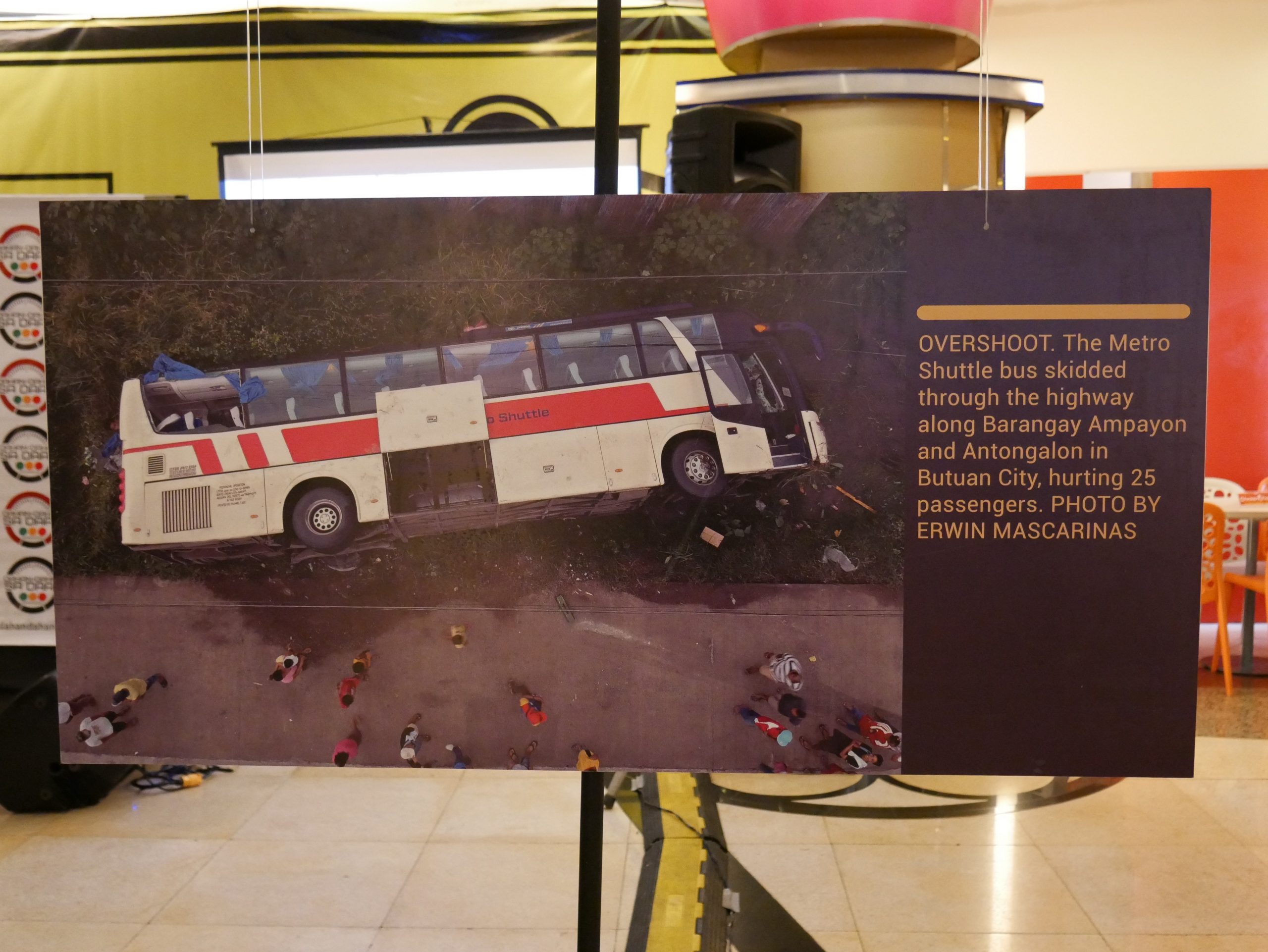

This situation is not unique to the Alaminos MVIC, but to all nine such centers in the country. It has become so dire that during the Senate inquiry on the Tanay bus crash that killed 15, Land Transportation Office Chief Edgar Galvante said that the entire system needs to be overhauled.

“Hindi nagpa-function ng maayos iyong ating mga equipment na ginagamit sa inspection kaya nagre-rely po tayo sa (The equipment we’re using for inspection do not function properly that’s why we rely on) physical and visual inspection,” Galvante said.

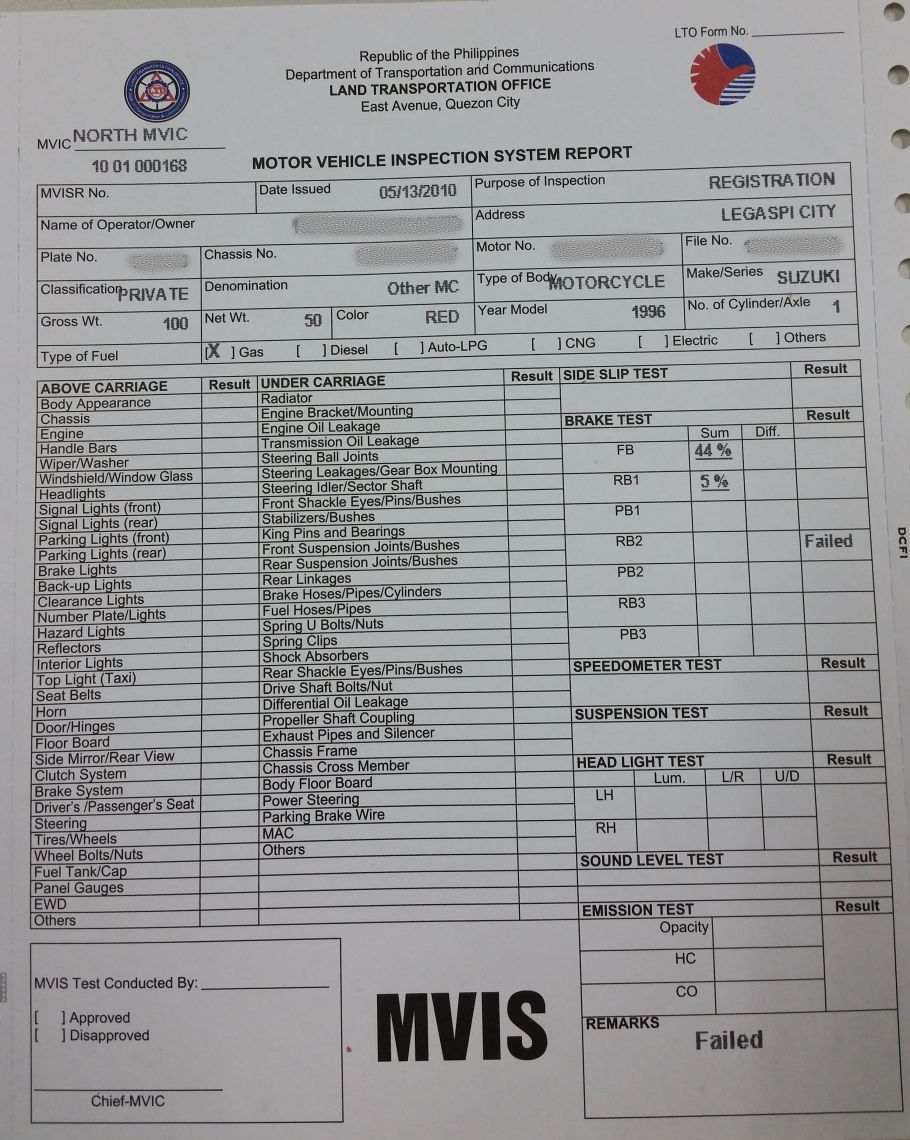

The MVIS report has 63 items on its checklist. Seven tests, including a brake test, emission test, a sound level test and a speedometer test, are done to evaluate all the parts of a vehicle.

Vehicles are “graded” at every test to determine if it’s safe to run on roads. If a vehicle gets a failing mark on even one test or if there’s a problem with a single part, the Land Transportation Office (LTO) will put “fail” in the motor vehicle inspection report.

The MVIS report lists 63 items that inspectors need to examine to determine a vehicle’s roadworthiness.

For a program that checks if vehicles are well-maintained, the government failed in the upkeep of the equipment used for doing so despite over P332 million allotted by the Department of Transportation and Communication (DOTC) 11 years ago.

The source of the funds is the road users tax, or the motor vehicle user’s charge (MVUC) paid by owners when they register their vehicles. It is said to be the government’s third largest source of income, after collections from the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) and Bureau of Customs (BOC).

The amount was set aside for a multi-year MVIS plan covering 2007 to 2010, but in 2009, a Commission on Audit (COA) report came out saying that some portions of the funds were misallocated or misused.

One misallocation highlighted by the COA was the purchase of six vehicles worth P5 million using MVIS funds in 2007.

The LTO Central Office acquired the vehicles despite an existing government order at the time suspending the purchase of motor vehicles in all government offices except the police and military.

Dr. Sheilah Napalang of the UP-National Center for Transportation Studies shows photos of the visual inspection done at the North MVIC in Quezon City. They took these photos during a visit in 2015. Photo by Verlie Q. Retulin

A study done by a team from the University of the Philippines National Center for Transportation Studies (UP-NCTS) did an assessment on how the road tax was used. The team, led by UP-NCTS Director Sheilah Napalang, discovered that a lot of MVIS equipment procured in 2006 were wasted.

Various COA reports over the years have pointed out that the culprit for the MVIS problems is LTO’s mismanagement of the project.

Four MVICs were established in 1992 in the country via a donation from the Japanese government. These are the North MVIC in Quezon City, South MVIC in Pasay City, San Fernando, Pampanga and Lipa, Batangas.

In 2006, these four were rehabilitated and the Alaminos, Laguna MVIC was conceived. The Alaminos equipment was delivered in 2007. It remained untouched for four years, while the inspection center was being built. It was only in 2012 when the Alaminos center began its operations.

“Ang daming naka-line up, walang natapos. (Inspection centers were lined up but were not finished.) Maraming nakabili na ng mga equipment, wala pang building (Many of them have already bought equipment even if there were no buildings yet),” Napalang said.

Napalang said MVIS buildings were not supposed to be used as offices, but in some regions the buildings doubled as such.

Another factor that contributed to the rapid deterioration of MVIS equipment was the lack of regular maintenance and calibration, as reflected in another COA report in 2012.

Napalang also found out in her interviews with the North MVIC in the LTO Central Office that evaluators lacked the skills to operate the equipment. “Mukhang hindi marami ang na-train. Nung umalis yung contractor hindi nila alam paano gamitin yung system talaga, (It looks like only a few were trained. When the contractor left, they didn’t know how to use the system),” Napalang said.

Each center is supposed to have a “fully computerized and automotive inspection/testing equipment.” But in the North MVIC, the computer system was not linked to the LTO’s Motor Vehicle Registration System (MVRS).

This means no real-time verification of results of the inspection, and a history of inspections made on the vehicle cannot be done. This makes the system vulnerable to manipulation, to be able to register a vehicle even if it failed the inspection.

In 2014, the DOTC began crafting a P19.3-billion MVIS Project to build more inspection centers all over the country. It was under a public-private partnership setup, where the private partner will “develop, operate, and maintain a network of MVICs that will perform inspection for all vehicles in the country.” The National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) board approved it in March 2015.

Galvante said during the Senate inquiry that they are moving forward with the project and are now in the process of choosing the supplier. He said that initial funding will still be sourced from the road user’s tax, and a part will be sourced from public-private partnership arrangements.

They plan to build one MVIC per region, proposing to acquire several mobile MVIS to cater to island provinces. The budget is estimated at P100 million per MVIC.

Galvante also implored operators to be mindful of their responsibility to ensure the safety of the riding public.

And the riding public should very well take heed, because the government office tasked to do so has relinquished that duty. Napalang said the only inspection the government is doing now is emission testing which analyzes pollutants coming from gas or diesel powered engines.

This story is produced under the Bloomberg Initiative Global Road Safety Media Fellowship implemented by the World Health Organization, Department of Transportation and VERA Files.