The Venice Biennale is in Manila! The Museum of Contemporary Art and Design, De La Salle-College of St. Benilde hosts the art works of the Philippine Pavilion (The Spectre of Comparison), 57th Venice Biennale, 2017. It runs until July 20, 2019.

The exhibition features the works of Lani Maestro (Filipino and Canadian) and Manuel Ocampo (Filipino and American), two transnational artists who traverse the art worlds outside their countries of birth, and drew their sustenance from being an outsider, an exile, and the Other in their art making.

The Artists

Lani Maestro (b.1957) an installation artist who moved to Canada in 1982. A fine arts graduate of the University of Philippines, her works deal with the idea of space, of how we occupy space, how it occupies us, and how others occupy it.

Manny Ocampo (b. 1965) studied fine arts at the University of the Philippines, and then moved to Los Angeles and San Francisco. It was in Los Angeles where he first achieved recognition with several solo exhibitions and his inclusion in the landmark exhibition Helter Skelter L.A. Art in the 1990s at L.A.’s Museum of Contemporary Art in 1992. In the same year, he participated in Documenta IX art show in Kassel, Germany. He returned to Manila with his family in 2003.

Josefina Cruz, the curator of the Philippine Pavilion, Venice Biennale 2017, is also the director and curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design in Manila.

Venice to Manila: The Works

The title of this exhibition is based on Jose Rizal’s novel, Noli Me Tangere. In the novel, Crisostomo Ibarra, Rizal’s protagonist, goes around Manila and while looking at the Manila Botanical Garden, he simultaneously remembers the well-kept gardens of Europe and compares Manila and Europe. It is here where the phrase el demonio de las comparaciones appears in the novel. Historian Benedict Anderson has translated the said phrase as “the spectre of comparison” and the title of his 1998 book of essays on Southeast Asia In an essay “The First Filipino,” Anderson wrote, “here indeed is the origin of nationalism, which lives by making comparisons.”

The phrase el demonio… serves as the framework for the art practices of the two artists, Lani Maestro and Manuel Ocampo, who represented the Philippine Pavilion in Venice.

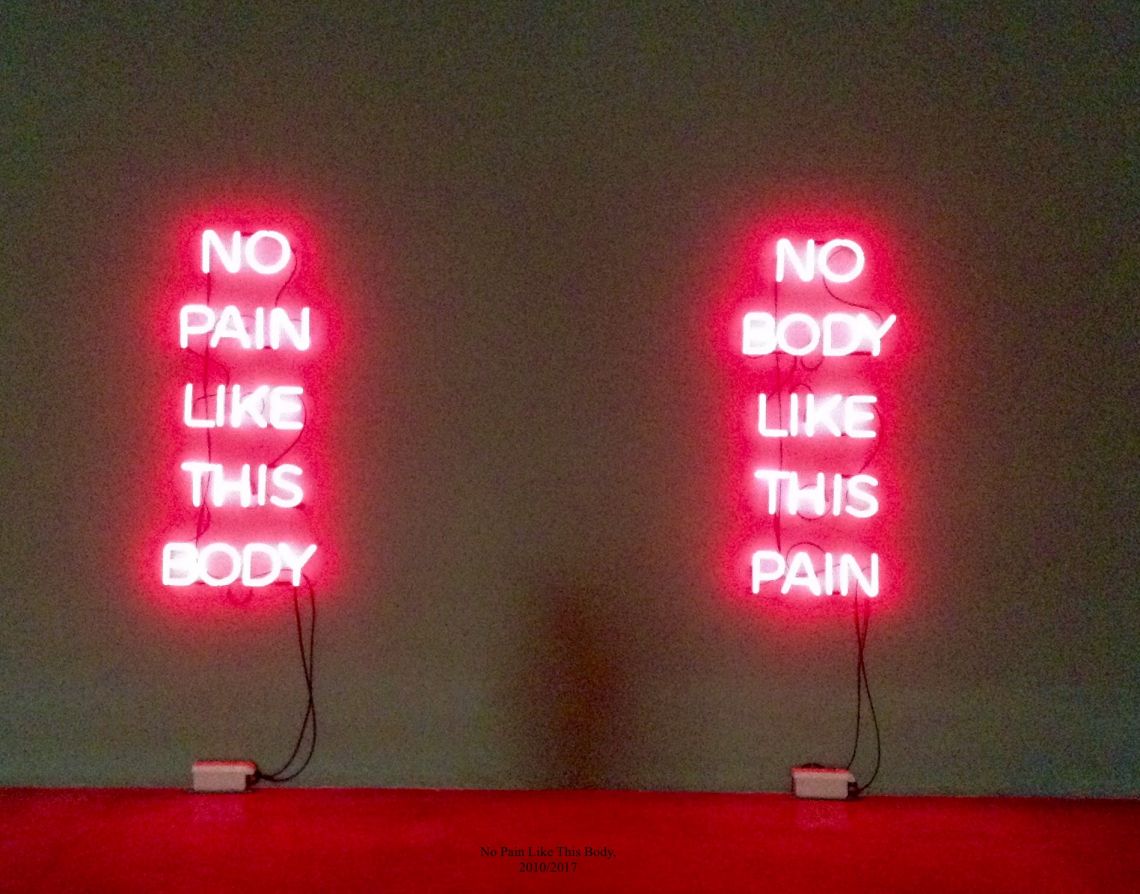

Maestro’s three installation works shown in Venice are in MCAD. It consists of two neon works of text — No Pain Like This Body, No Body Like This Pain (2010/2017) in ruby red, and If you must take my life, Spare these hands, in blue.

The first one is inspired by Harold Sonny Ladoo’s novel No Pain Like This Body, about growing up in poverty and violence in Trinidad and Tobago; Ladoo was a Canadian immigrant from Trinidad and Tobago. It was also influenced by Maestro’s exposure to Downtown Eastside in Vancouver, with its homelessness, drug abuse, mental illness, and prostitution. The second work, these Hands (2017), is taken from the last two lines of a poem, Flowers of Glass by Jose Perez Beduya, a Filipino writer based in New York.

Maestro’s third installation is entitled meronmeron, wooden benches where anyone can sit and gaze at the artworks, and reflect on them. And write some messages or graffiti on the benches.

The Profane and the Sacred

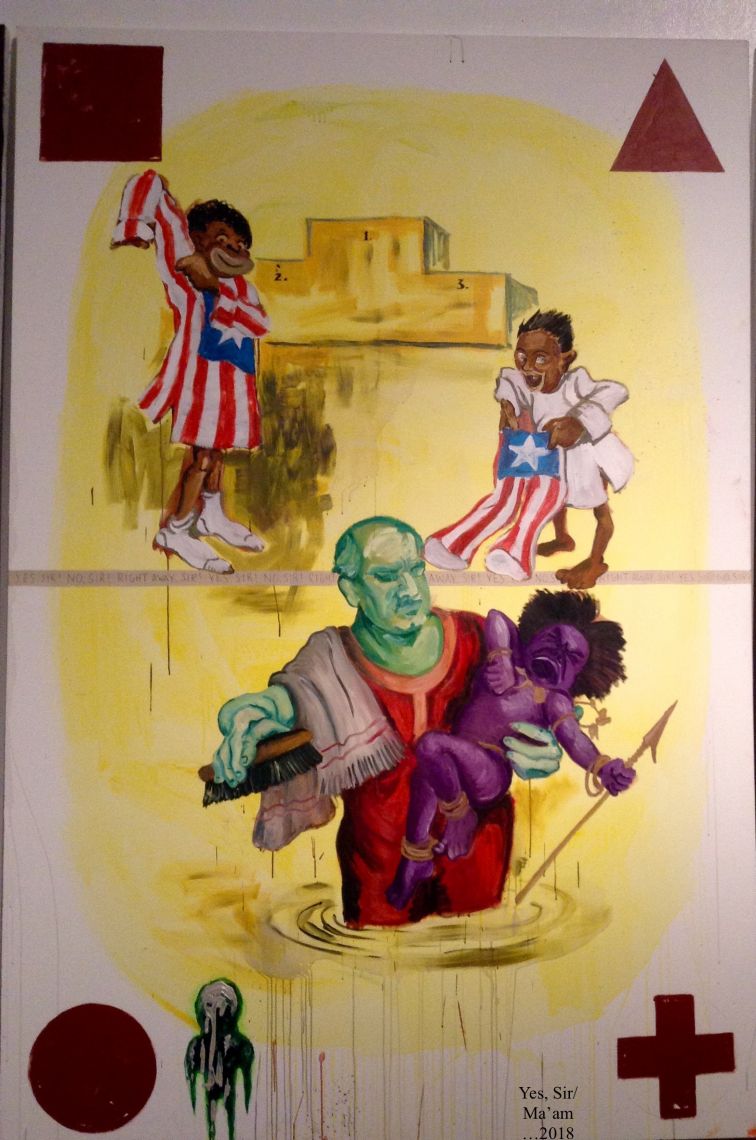

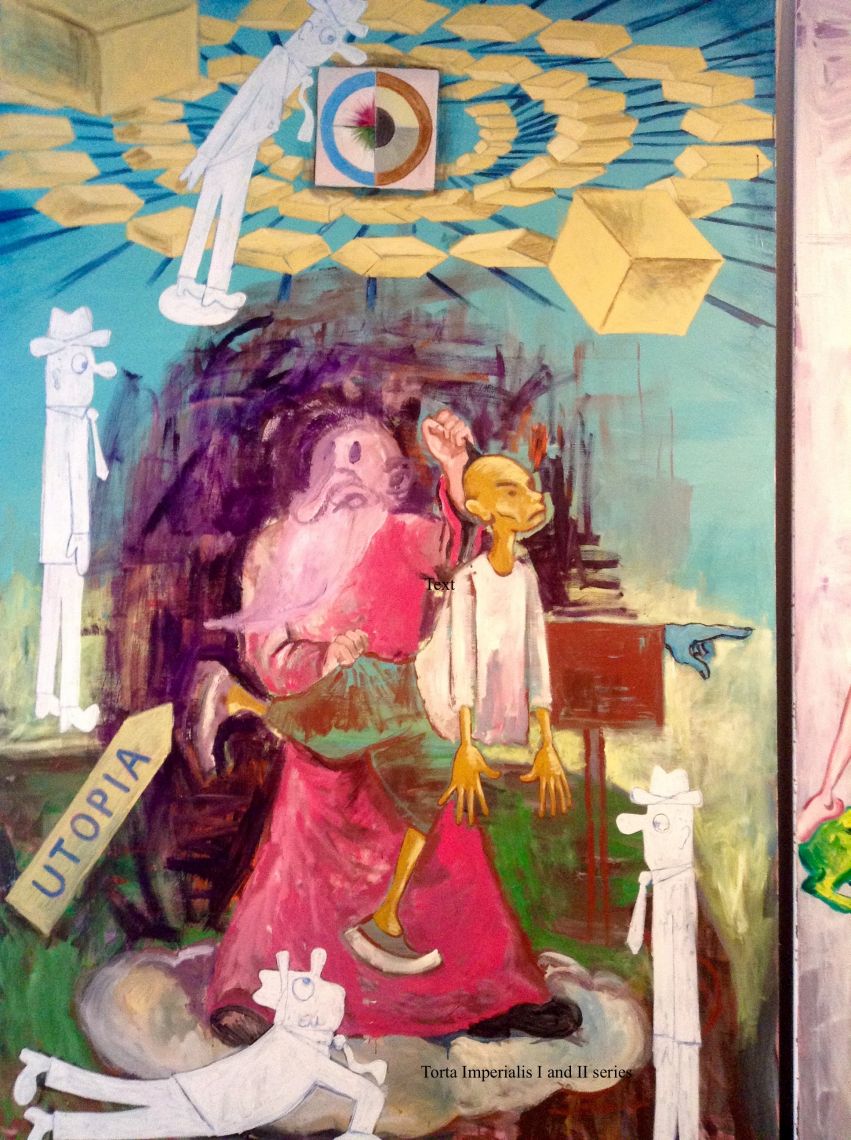

In contrast to Maestro’s minimalism, the explosive energy of Ocampo’s paintings confronts and unsettles us: violent, colorful, gruesome, and profane.

Manny Ocampo presents a total of 15 paintings in MCAD. Six of the eight original Torta Imperialis I and II paintings plus Twelfth Station, 1994 shown in Venice are exhibited and some additional works. Populating his crowded canvas are crosses, body parts, intestines and sausages, demons, skulls and skeletons, owls and bats, hooded figures, dressed-up monkeys, blacks with disc-inserted lips, and floating blobs. Using allegory and metaphor, his 1990s paintings were critical of Western colonialism, ignorance and superstition, and authority and religion.

Ocampo is fond of using cartoon figures as an irreverent counterpoint, especially censored characters from Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies for their racial and ethnic stereotypes. The works of the legendary cartoonist Tex Avery and abstract painter and cartoonist Ad Reinhardt pop up now and then.

He would also add as collage a printed prayer as seen in Twelfth Station with a giant cockroach as the crucified Christ or a box of white shoe polish to Why I Hate Europeans, 1992.

Layered with references to Roman Catholic religious icons, pop culture, images from the Philippine-American War, and colonial history, Ocampo’s paintings inquire into questions of identity, nation, nationalism in a time of discontent and migration.

Josefina Cruz has noted: “Ocampo’s and Maestro’s practices are both invested in the Philippines as initial inspiration, but are hardly beholden to it.”