Amsterdam is one of the world’s best cities in which to talk about the importance of humanity. It is a place of tolerance, law, social inclusion, religious, artistic and press freedom, and vital pluralism.

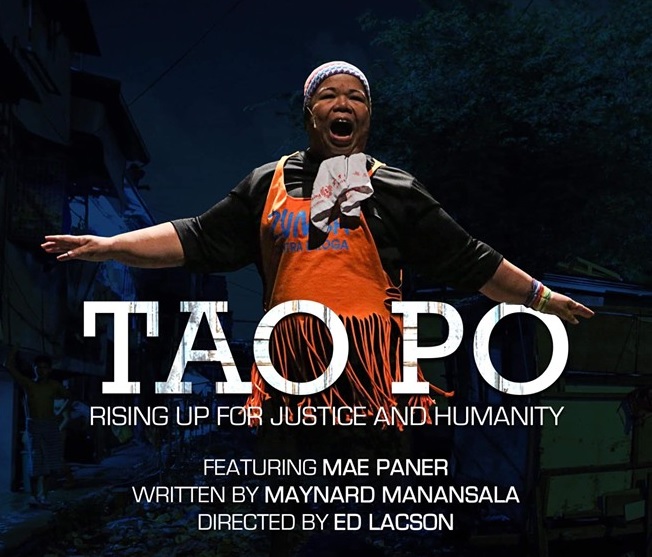

Mae Paner, the Filipino actress and political satirist, has come to tell stories from the frontline of President Duterte’s vicious drug war. She calls for compassion and justice. Those who are already morally outraged at the astonishing impunity and debasement of human rights in the Philippines listen to her.

But it’s not her intention just to “preach to the choir,” she says. She wants the attention of the hostile trolls, fanatics and haters whose unyielding support for their president extends to cheerleading on his drug war and the extrajudicial killings of drug pushers and addicts. Her sense of urgency is well founded. Duterte continues to be popular despite the bloodletting. The human toll of the President’s campaign, human rights groups say, has reached close to 30,000.

Mae Paner in Amsterdam. Photo by Diego del Oro.

Paner is the sole performer in “Tao Po”, a four-act monologue based on the true heart-rending experiences of four people in the thick of the drug war: a photojournalist who nightly covers the killings; a policeman who had publicly admitted to being a paid killer for Duterte; a woman whose son and husband were killed in police operations; and an orphaned child grieving for her murdered parents. The characters she depicts are scarred by terrible loss and mental trauma. First performed in 2017 in Manila, and currently completing a gruelling six-city European tour organized by Rise Up! a network of clergy and human rights advocates, “Tao Po” is the most courageous and artistically radical theatrical response to Duterte’s regime yet staged.

Paner is known for her loud mouth, great heart, and incisive brand of political humor. Her excoriating comedic skits against corruption and social injustice enjoy thousands of views on YouTube. Her stage moniker ‘Juana Change,’ a play on the phrase ‘want to change,’ attests to her ardent hope that things can and should be different – change as catharsis and transformation.

Paner and I speak just before her performance. She is dressed all in black, sports spiky crew-cut hair and is in a somber mood. She visited the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague to submit more cases of extrajudicial killings, which may have felt depressingly unpromising.

Formal complaints alleging Duterte’s commission of crimes against humanity were filed in April 2017. Two years on, the ICC has not gone beyond the preliminary examination stage to launch a formal investigation. Paner battles against a sense of futility with self-belief. “I do what I need to do and I judge myself on what I am able to do. The result is not [my] problem. If there is one call of this play it is for people to be in touch with their humanity and to realize how connected we are to each other.”

The play, she tactfully insists, is not an attack on the President. She resists partisanship and claims to stand “for unity.” She doesn’t want to alienate anyone in the fight against the common enemy. And who or what does she regard as the common enemy? “For now,” she says ironically, “it is Duterte.”

Ciriaco ‘Jun’ Santiago, a brother belonging to the Catholic Redemptorist order, is with the show. He practices the vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, but unlike ordained priests he cannot take mass or give confession. Being a brother, he thinks, enables him to relate closer to ordinary people. “There’s always a disconnection between the laity and the clergy,” he says. Solely supported by the Redemptorist order, Jun has been photographing drug war victims and giving much needed practical assistance to their families since 2016. He arranges help for funeral expenses, counseling and employment for survivors. An unassuming man, he works in collaboration with the award-winning photojournalists Ezra Acayan, Raffy Lerma and Vince Go, whose powerful images significantly raised international public awareness. Together they cover the slum areas of Caloocan, Tondo and Bulacan where the worst of the killings have occurred.

Photojournalist Jun Santiago. Photo by Diego del Oro.

Photographing murders and following the police beat night after night (photojournalists who cover the drug war are known as the ‘Nightcrawlers’), brings out the worst side of their natures, Jun tells me. Often emotionally and physically beleaguered, photojournalists have to find ways to deal with their own shock, anger, frustration and despondency.

Jun has a confession: using fake social media accounts and posting under pseudonyms, he verbally abuses supporters of the drug war. “I love to troll them,” he says, chuckling. He stalks online Duterte supporters and lets rip, castigating and spewing scornful words. “I’m always happy when I use these accounts. You have to try that,” he says smiling broadly for the first time in our conversation. “We have a certain demon in our lives that needs to unleash evil.” Two hours of private trolling a day and typing “You motherfucker” anonymously, he tells me, is therapeutic.

And so is the act of crying in public and telling one’s story. Kathy and Marissa are two mothers who travel with Tao Po. At the end of the performance, they talk about how their young sons were shot dead by police in cold blood. One boy was gunned down after he tried to run during a drug bust; the other was accused of belonging to a drug syndicate. These flippant, dismissive explanations from the police are enough of a justification for the murder of these boys and to obstruct attempts at any impartial investigations. Both boys were killed in 2017 and like the thousands of other victims of Duterte’s drug war, they were from families hard-pressed to give children consistent care, education, proper shelter and food, let alone to pursue justice in their name. The mothers sobbingly recall the lives and personalities of their sons, giving proof, as if proof were needed, of the boys’ humanity.

To be sure, there were plenty of sympathizers, liberals and leftists sitting in the Amsterdam theatre that night. I recognized a Dutch academic, a documentary filmmaker and a judge. A Filipino bishop of the Aglipayan church from Davao later identified himself. Critical of the President, he had fled Davao in fear of his life. Then there was the young woman who admitted that she had once supported extrajudicial killings because her father had been a drug lord. He went to prison and has now been released. She is glad he is still alive. She finished her story in floods of tears.

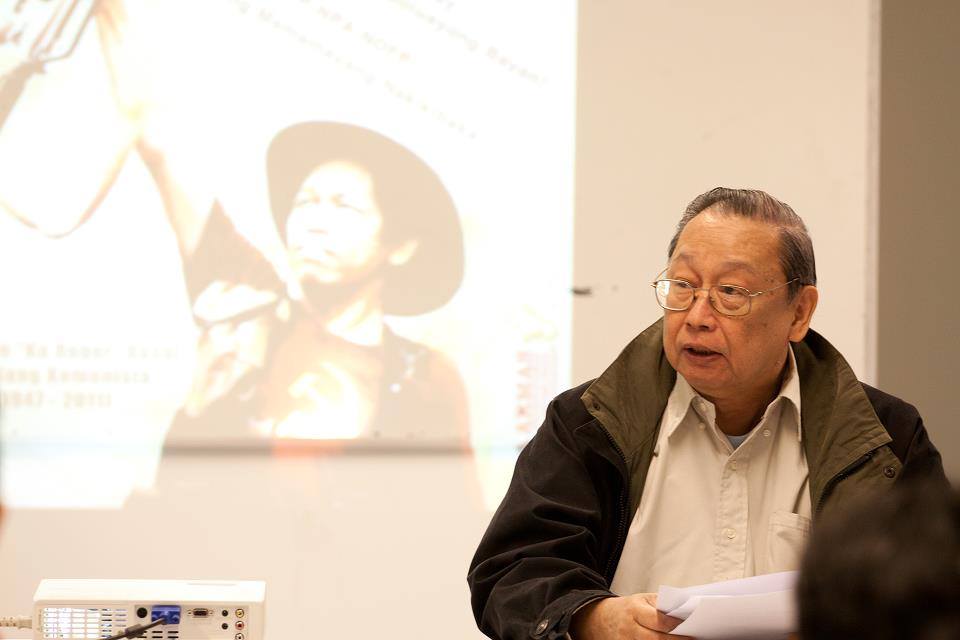

Emotional outpouring is not for everyone, however. Occupying half a row of seats were core members of the International League of Peoples’ Struggles (ILPS), a cheerless anti-imperialist group founded some years ago in the charmingly bourgeois Dutch provincial city of Zutphen. I found myself sitting, with some unease, near the ILPS chair emeritus, better known as Jose Maria ‘Joma’ Sison, the Great Helmsman of the Communist Party of the Philippines. During the performance I glanced over at him and wasn’t entirely sure whether or not he had fallen asleep.

Joma Sison watched Mae Paner’s Tao Po in Amsterdam. Photo from Sison’s Facebook page.

Now aged 80, Sison looks physically diminished. He is saggy and jowlly and wears ineffective hearing aids in both ears, I am almost shouting when I talk to him. “The peace talks with the government have collapsed again,” I yell. “What next in your love-hate relationship with Duterte?” Not long ago, Communist cadres including Sison were photographed doing Duterte’s trademark fist salute. Both sides have now U-turned. The government has issued a warrant for their arrest and is pushing for extradition based on the revival of a multiple murder charge filed in 2007 against Sison and others.

Sison has resided in Utrecht throughout his 30-year exile in the Netherlands. He describes his status as “legally clean”.He has come to see Tao Po with many communist supporters, including two of his most trusted top-ranking comrades, Fidel Agcaoili and Luis Jalandoni, who are both seasoned negotiators of the National Democratic Front. Of course, peace negotiating comprises but a small fraction of their resumés. Back in 1971 these very same key Communists are suspected by historians of planning and executing the deadly Plaza Miranda bombing.

Joseph Scalice, in his outstanding University of Berkeley, California, doctoral dissertation on the Communist Party, pins Agcaoili at that time in Beijing negotiating an arms shipment for the Communist Party.

The fact is, the intimate ties between Sison, the Communist Party he heads, and Duterte can be traced back to Davao since at least 1987, after Duterte became mayor. At that time, the NPA, the armed wing of the Communist Party, and Party cadres operated with near absolute impunity in Davao. While NPA insurgents clashed with military forces, the former were also responsible for a wave of abductions, torture and summary executions against those found to have committed “crimes against the people”. Military informants, abusive police officers and criminals, but also civilians, were targeted. The city was infamously known as the “murder capital of the Philippines”. Duterte exacted compromises from the Communists, formed friendships with cadres and reduced the abuses and killings by NPA insurgents.

Scalice tells me how the Communists and Duterte tactically supported one another from the late 1980s onward. Party front groups, notably Bayan Muna, ran for and took seats on the [Davao] city council on a joint party slate with Duterte. The NPA forged close ties with the mayor. As Scalice recalls, Leoncio Pitao, a top NPA commander, and Duterte were reportedly close personal friends. At Pitao’s wake in 2015, even former Davao city police chief Vicente Danao came to pay his respects.

Carlos Conde, a former journalist who worked in Davao during Duterte’s mayoralty, and now a researcher for Human Rights Watch, summed up Duterte’s harmonious alliance with the Communists in this way: “The Communists have a need to assert their belligerent status. They need to assert that they are a revolutionary group. The only way that this can be shown is if the leader of the political elite that they are fighting recognizes them and what they are capable of. That is a dynamic that happened in Davao.”

Sison doesn’t seem to have any qualms about getting into bed with corrupt murderers. Speaking to me with emphasis, he admits: “From the beginning I knew Duterte was rotten…I knew he was killing people without due process, even killing children who were caught as burglars. He and his son were involved in smuggling. I knew ship captains who would dock at Davao and Duterte himself would be responsible for bringing out the goods and ignoring the customs office. He is a bureaucrat-capitalist who makes money out of his office.”

With that, a few women gather round Sison for selfies. He tells me to follow his Facebook account, where, he says, he spends every morning tracking and commenting on Duterte. However denunciatory they maybe, Sison’s words have a hollow ring. The Communist past is littered with unprincipled opportunism and unaccountable killings.