His death was an extrajudicial killing committed by the elitist cabal of Emilio Aguinaldo. Why have we left it unpunished? We have made Andres Bonifacio a victim of state impunity until today.

Of all lamentations on his death sentence by a kangaroo court and his cold-blooded murder in a secluded mountain site, Apolinario Mabini’s remains the last word, that Bonifacio’s assassination was “the first victory of personal ambition over true patriotism.”

Aguinaldo wanted to wrest control of the revolution in the only way his men, acting like hired goons, knew how: skullduggery and thuggery. Aguinaldo and his elite cohorts committed a crime that until now goes scot-free. Only Manuel L. Quezon had the gumption to call Aguinaldo to task for his role in the crime, but that was because of partisan reasons when the two faced each other as presidential candidates in the 1935 elections.

Listen to our usual descriptions of Bonifacio. He was “unschooled.” Yet the choice of books he had read equaled those of an ilustrado’s: Victor Hugo’s Les Miserable, Alexandre Dumas, Jose Rizal’s novels, books on the Philippine penal and civil codes, the history of the French revolution, the Holy Bible, Eugène Sue’s The Wandering Jew, lives of American presidents, etc. He spoke English, which he learned while working as an agent in the British trading firm J.M. Fleming and Company, the forerunner of today’s Asian investment bank Jardine Fleming. He later transferred to the German trading firm Fressell and Company.

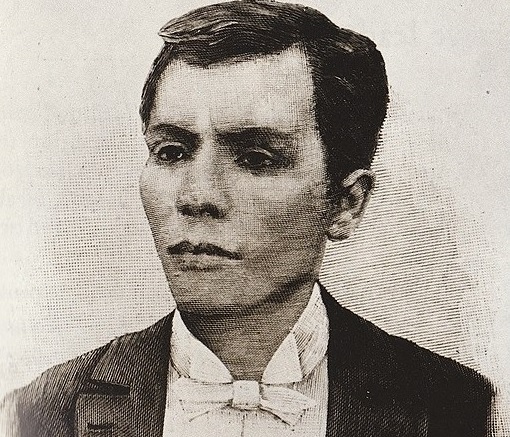

We have dressed him stereotypically in camisa chino and rolled-up red trousers, but his only extant photo showed him dressed in Western tuxedo complete with jacket, bowtie, and wingtip collar. By pigeonholing him as such, we actually surrender to the Aguinaldo camp’s disparagement of Bonifacio as poor, unlettered and unschooled. He is commonly portrayed as an “indio” but how can that be when his mother Catalina de Castro was a Spanish mestiza.

Not a few historians, among them UP’s Milagros Guerrero, Ramon Villegas and Xiao Chua advocate for Bonifacio to be declared the first president. He should be. He had a working cabinet, he commanded an army. The transcript of his sham trial even identified him as “the President of the Revolution.” Our nationhood began from that revolution.

But by starting our republic from Aguinaldo only means we are still deceived by the naked power’s coup d’état he had instigated against Bonifacio, not to mention the dagdag-bawas rigged election Aguinaldo’s men did at the Tejeros Convention where pre-filled ballots outnumbered actual voters. Even Artemio Ricarte admitted that Aguinaldo’s election was “not in conformity with the true will of the people.”

More than a century has now passed since the deaths of Rizal and Bonifacio, legislation is now ripe to declare both as national heroes as an affirmation of correct sentiment. As it is, treating Rizal as primus inter pares has created a preponderance of Rizal adoration. Even our official overseas cultural centers are named Sentro Rizal.

Unlike Rizal, no province is named after Bonifacio. We can only count with the few fingers the municipalities in the country named after him. Actual praxis has actually relegated him as only secondary to Rizal. That must be corrected because it is wrong. Moreover, it will finally put to rest the debate on who is the better national hero. Why is that debate continually fostered? That debate is not foolish. It is precisely concomitant to our denigration of Bonifacio as only a runner-up to Rizal.

To restore Bonifacio to his rightful place alongside Rizal, it also becomes imperative to try to find his remains once again, to be buried in a rededicated Bonifacio Monument. More than seven years ago, the forensic anthropologist Amy Mundorff of the University of Tennessee embarked on finding unmarked human graves using remote sensing technology called light detection and ranging or LIDAR.

Nitrogen is one of the many chemicals that decomposing bodies release. It is also an essential mineral for plant growth. The change in soil chemistry from the extra nitrogen could alter the chemical signature of the plants growing over the grave. As a result, vegetation over the graves can reflect red and infrared lights differently, enough to be picked up by LIDAR strapped to the belly of an airplane or helicopter.

No doubt LIDAR is a costly process. A scanner used to cost US$200,000 but it can be loaned from the Remote Sensing Center of the US Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California. Let the state prove to the Filipino people that it is willing to invest on righting historical truth instead of on plunderous confidential funds.

If successful and confirmed by DNA tests, let there be a state funeral for Andres and Procopio Bonifacio with the day itself declared a national holiday. But even if the remains are not found, the National Historical Commission must settle once and for all a very sensitive issue: transfer his monument to the Luneta.

In 2005, National Artist Alejandro Roces voiced his adverse opinion on the relocation of the Bonifacio Monument in Caloocan to give way to the expansion of the Light Rail Transit. One distinctive fact of that beautiful monument was that it was constructed by contributions from veteran Katipuneros instead of state funds. Roces, however, offered prudence: “If it is going to be transferred, it should be in a more prominent place, a historical soil where more people will be able to appreciate Bonifacio’s great contribution to the Philippine Revolution.”

The Luneta is not an inconsequential place. The Bonifacio Monument was a designed as a grand national memorial. It should lie in the national capital, not in a component city of Metro Manila.

Historian Xiao Chua argues on how monuments need a human anthropological space. “Luneta is the heart of the Republic, the cradle of national memory.” Kilometer 0 in fact starts from it. With Bonifacio and Rizal finally together in the Luneta, the former’s monument can finally stand once again on a human space where we can tell the stories of our national anthropology.

The distinguished urban planner architect Paolo Alcazaren was against moving the monument. “The Bonifacio Monument was intended to sit at its site specifically to commemorate the historic spark ignited there and that led to the culminating events of 1898.” But like Roces, he had written that as a reaction to the expansion of the LRT to connect to the Metro Rail Transit line spanning Edsa.

In 1918, when Act No. 2760 was passed by the Philippine Legislature to build a monument in honor of Bonifacio, a small statue of Bonifacio by the sculptor Ramon Martinez was already up on the nearby site where the Balintawak cloverleaf is. The statue was relocated to stand outside Vinzons Hall in UP Diliman.

The monument contains a tableau of 23 figures in bronze that tells the narrative of the revolution. The more reason that it should be on a site where it can be meditated upon, not on a place where there is nothing but a cacophony of traffic gridlock. No one goes there for Bonifacio anymore, and certainly not to stir up the passion and zeal of a nation still oppressed by enemies because that is no longer possible in Monumento. The place reeks of unplanned and unmanaged urban sprawl. Furthermore, it no longer gives justice to the great genius of the National Artist Guillermo Tolentino.

The site was chosen to signify Bonifacio guarding what was then the northern entrance of Manila. That open space is no longer true as the confines of Metro Manila have been bursting at the seams.

But the Luneta will always remain the Luneta. By relocating it there, the rotunda that is inherently part of the Bonifacio Monument can be retained, not demolished, and the original Martinez sculpture returned to signify the Cry of the 1896 Revolution that took place in that geographical zone (the exact location of which continues to be disputed to this day anyway, reminds historian Ambeth Ocampo).

Ambeth Ocampo also relates that the transfer of the Bonifacio Monument was first contemplated on during the martial law years. There was a fear, however, that the more imposing 45-foot pylon of the Bonifacio Monument and tableau might upstage the Rizal Monument. Historian Teodoro Agoncillo once opined that Bonifacio and Rizal should be honored “side by side.”

The greatest irony surrounding Bonifacio is he is largely ignored, his assassination site in Cavite honored with a swimming pool and merriments to entice people to visit because it is far. Aguinaldo had acted as a counter-revolutionary, true to his class interests, when he had Bonifacio eliminated. True enough, he later compromised with the colonizers. Look at our government today – a government of counter-revolutionaries who serve the priorities of the rich and the powerful.

Let us stop the ridicule of Bonifacio.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.