It’s unfathomable how people refuse to see then Pres. Rodrigo Duterte’s betrayal of the Philippines, as was made evident in his acquiescence to China’s dismissal of his country’s 2016 victory in the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, as well as the Philippine Maritime Zones Act and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

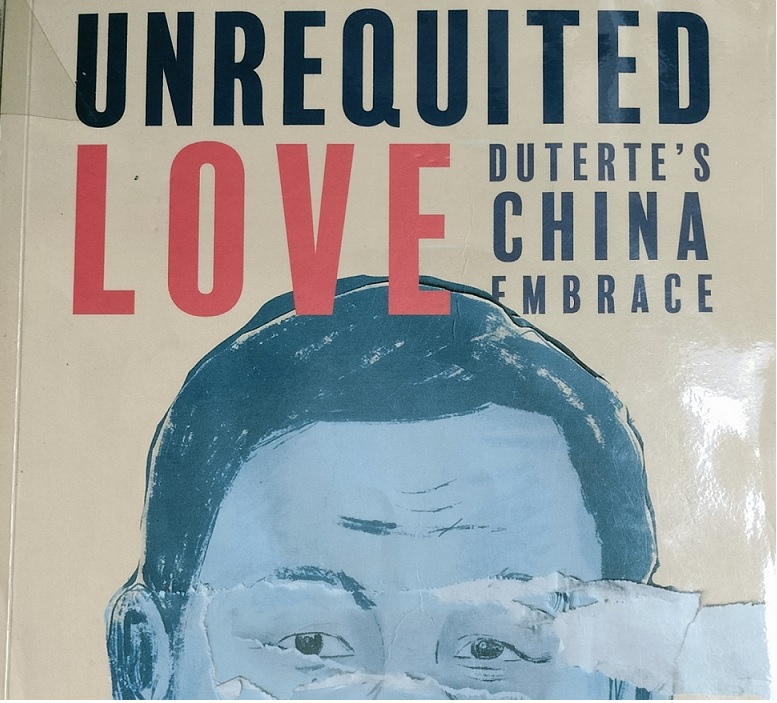

Marites Dañguilan Vitug and Camille Elemia recount in their book, “Unrequited Love: Duterte’s China Embrace” (2024), the incidents of betrayal, including how Duterte referred to the ramming and sinking of the Filipino-owned wooden fishing boat F/B Gem-Ver at Reed Bank by a large steel-hulled Chinese vessel as a “little maritime incident.” Or how he denigrated the arbitral court’s ruling favoring the Philippines, calling it a “piece of paper” fit for the wastebasket in a late-night address to the nation.

Vitug and Elemia raise the question: What can be done to make Filipinos believe that Duterte’s embrace of China is plain treachery? Their book addresses the issue backed by extensive field interviews and archival research, and examines Duterte’s psyche in his preference for China.

Grudge

“Unrequited Love” begins with how Duterte’s anti-US sentiments were first stirred by his activist-mother, Soledad, who told him of America’s crimes during its colonization of the Philippines. These sentiments were reinforced just as his nationalist viewpoint was strengthened after Jose Ma. Sison, founder of the Communist Party of the Philippines, schooled him on “the evils of American imperialism.”

Duterte’s personal resentment towards the United States started festering in the early 2000s because of certain incidents, according to Vitug and Elemia. First, in a trip to the US from Brazil, he was brought to an interrogation room after failing to show the immigration officer a letter of authority to travel and his explanation of being a Philippine congressman wasn’t accepted.

Second, the rejection of his tourist visa application because of supposed human rights violations in Davao City made him miss witnessing the birth of his youngest child in the US. (Another version states that the consul wasn’t convinced by his answer that he’d return home even if he was offered $10,000 and a lifetime of free visas.)

Third, the matter of Michael Terrence Meiring, a self-described treasure hunter but suspected CIA agent. Meiring was in in his Evergreen Hotel room in Davao City in 2002 when the explosives he was keeping accidentally went off. The injured Meiring was taken to hospital, but alleged FBI agents took him back to the US before local officials could interrogate him, and without their knowledge.

Duterte took these US actions as a personal affront, according to Vitug and Elemia. As Davao City mayor, he blocked the US proposal of holding joint US-Philippine military exercises in Davao, saying the American soldiers were magnets for terrorists and criticizing their “arrogance and pretended superiority.” As president, he threw in his lot with China over America, declaring that Chinese President Xi Jinping understood him.

In examining Duterte’s supposed grudge against the Americans, the authors reveal his contradictory personality. They cite a case in point: He repudiated an old imperialist ally for another imperialist, to which he gave the key to the country.

Chinese ties

Davao is no strange land for the Chinese. Vitug and Elemia write that after World War II, Chinese businessmen flocked to the city and opened businesses (milling, shipping, construction) that grew over the next decades. Duterte befriended the succeeding generations of Chinese Filipinos, who later helped fund his programs and political campaigns; they lived in symbiosis. Davao became a safe city for them, much to their relief, having been, prior to Duterte’s mayorship, frequent targets for extortion, harassment, kidnapping, and murder. (Davao is the first Philippine city to use CCTVs everywhere, with some cameras installed at checkpoints, the airport, and crowded areas fitted with face-recognition technology.)

The Chinese Filipinos saw in Duterte their hope and “did everything they could to support him because only he had the power to end the terror,” write Vitug and Elemia. “This would extend to Duterte’s daughter, Sara, when she became mayor.”

Duterte continued the bonhomie toward Beijing like then Pres. Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, who welcomed Chinese aid and investments into the country. But while Arroyo was also friendly with the U.S., Duterte wasn’t. The Philippines and China became defense partners in 2004 through the Annual Defense and Security Talks, an alliance that President Benigno Aquino III observed until he took Beijing to court, add Vitug and Elemia.

In contrast to Aquino and Arroyo, Duterte made China his bosom buddy. China followed Duterte to the siege of Marawi in 2017, seizing the opportunity to foster ties with the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) via two separate donations of rifles worth ₱539 million in total, write Vitug and Elemia. Intriguingly, the AFP didn’t use the Chinese-made rifles and gave these — except for 100 kept for testing — to the Philippine National Police. The AFP “[doubted their] quality and dependability,” preferring their standard firearms of Western-made M16 rifles and M4 carbines, the authors wrote.

Business deals

“Unrequited Love” reads like a John Le Carre thriller, but it maintains data integrity. It exposes business deals like “Safe Philippines,” a project that expanded Davao City’s security monitoring office and 911 center through a loan of $337 million from China. The signed memorandum of understanding proposed to assist 18 local government units to reduce the crime rate, improve emergency response time using advanced technology, and upgrade the 911 emergency system.

The project’s target operational year was 2022, but then Senate President Pro Tempore Ralph Recto discovered that the project was a threat to national security because it would collect the data of Filipinos. Contractor-supplier Huawei was mandated to cooperate with Chinese intelligence agencies based on China’s National Intelligence Law. Recto blocked the government’s share payment of ₱7.42 billion, but Duterte vetoed it. Ultimately, however, “Safe Philippines” fell through with the delay in China’s share of the funding.

“Unrequited Love” also lays bare China’s infiltration of the Philippines’ conventional and social media, emphasizing China’s tactical shift from “soft power” (or the use of persuasion and attraction — not coercion — to achieve a country’s foreign policy objectives) to “sharp power” (or the use of covert means — misinformation and stealthy media campaigns — to carry out a foreign government’s goals in a target country).

Vitug and Elemia write of the supposed collusion of certain newspapers that published op-ed pieces presenting China’s version of events, like the “real Xinjiang” versus the Xinjiang where the Uyghurs were persecuted, or reprinted articles from Chinese state media. They point out as well that the Philippine News Agency published Xinhua articles belittling Philippine interests and policies, including a commentary that called the arbitral ruling an “ill-founded award.”

Significantly, the content sharing reflected the Chinese saying jiechuan chuhai (“borrowing a boat to go out to sea”) and the manipulation of Filipinos. “The [Chinese government] would ‘borrow’ established media outlets as a ‘boat’ for spreading and legitimizing Beijing’s narrative,” the authors explain.

Think tanks helped advance the China agenda, the authors say, citing as an example how the Philippine-BRICS Strategic Studies promoted pro-Beijing and Duterte content, and attacked the West and local opposition.

Economic adviser

“Unrequited Love” examines the circumstances of Michael Yang, a native of Fujian province who moved to Davao City in the late 1990s and eventually became Duterte’s economic adviser. Yang’s public appearances with Duterte proved an easy ticket to get politicians’ attention and trust, according to the book.

While Duterte denied Yang’s appointment at first, citing its unconstitutionality, Yang didn’t hide their close relationship, the authors write. The reception desk at his Makati office had a big sign with gold Chinese characters stating: “Office of the Presidential Economic Adviser.”

As narrated by Vitug and Elemia: Yang facilitated the entry of the Taiwan-registered Pharmally International Holding Company into the country. Registering as Pharmally Pharmaceuticals Corp., the supplier of personal protective equipment, face shields, and face masks was managed by young officers including Yang’s translator. During the pandemic, the Philippine government bypassed Filipino manufacturers and suppliers for Pharmally, giving it the “biggest pandemic deals in 2020 and 2022” amounting to ₱11 billion. Yet the facts about Pharmally were overlooked: a small paid-up capital of ₱625,000; no previous business transactions with the public and private sectors; zero technical capabilities; and a company president wanted in Taiwan for breach of trust.

The authors disclose other controversial China-funded projects. The donated drug rehabilitation center in Sarangani was built by China State Construction Engineering Corp., China’s largest building contractor. It was banned by the World Bank in 2009 for six years for alleged corruption and was blacklisted in the Philippines in 2004 for six months over alleged violations of government procurement law.

The Chico River Pump Irrigation Project had as contractor China’s CAMC Engineering Company Ltd., which was cited by the Philippines’ Commission on Audit for irregular contracts. In Bolivia, its country representative was imprisoned in connection with the “biggest corruption scandal” involving railway and road projects. In Ecuador, it was accused of bribing a former state comptroller with $1.3 million.

DFA

“Unrequited Love” raises a critical component in Duterte’s embrace of China: the enablers. The Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) under then Foreign Secretary Alan Cayetano was markedly silent when, the authors point out, it was one of the institutions that provided solid support to the arbitration case. They write that Cayetano rejected talking points by staff working on China issues, and stopped them from organizing forums to raise public awareness on the importance of the arbitral award. As well, he avoided filing diplomatic protests against China.

Vitug and Elemia cite the contrast between Cayetano and his successor, Teodoro Locsin Jr. They write that if Cayetano suppressed the DFA, Locsin removed the gag. He agreed to file diplomatic protests and made strong statements in public and during meetings in the DFA. Tellingly, the dissimilarity of the foreign secretaries underline that Duterte left policy and operational details to his Cabinet officials while he focused on his war on drugs and anti-crime campaign.

Then Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana spoke out against China, too, write Vitug and Elemia. He urged the continued filing of diplomatic protests against China while speaking about its “strong interest in the West Philippine Sea.” But Lorenzana didn’t completely antagonize China, the authors say. He allowed Dito Telecommunity to build cell towers in military camps, ignoring warnings from senators and the military of the threat to national security. Dito was a joint venture between Duterte crony Dennis Uy and China Telecom.

Locsin’s stance led to change — from nondisclosure to full revelation — in the way China’s aggressive actions were broadcast post-Duterte. The change, say Vitug and Elemia, was accelerated by China’s use of military-grade laser in 2023 on a Philippine Coast Guard (PCG) vessel assisting in the resupply mission at Ayungin Shoal.

Patriotic duty

It’s now 2025 and China’s aggression continues. On Jan. 11, according to reports, the PCG faced the China Coast Guard (CCG) vessel 5901, the “Monster,” in Zambales. The PCG spokesman, Commodore Jay Tarriela, said the Monster replaced the smaller CCG 3304 in sustaining Beijing’s presence in Zambales waters, but it was “gradually pushed away” by the PCG’s BRP Teresa Magbanua. On Jan. 25, CCG 3103 used a long-range acoustic device capable of damaging hearing to prevent the PCG’s BRP Cabra from getting closer to the Chinese ship, added Tarriela.

Benigno Aquino III stopped China’s encroachment into Philippine waters when he took it to court, and won. But Duterte dismissed the victory and rolled out the red carpet for China, with the Philippines getting the short end of the stick.

“Unrequited Love” keeps the voices of history and protest alive. It presents a history lesson on how a president and his enablers allowed a foreign power the run of the Philippines, duped Filipinos into believing it was for their betterment, and treated Filipinos as second-class citizens. It challenges Filipinos to separate rhetoric from truth. It shakes them out of the misguided belief that fate, and not leaders, steers the national development.

Finally, it reminds Filipinos of their nationalist duty to question the embrace of a foreign power.

“Unrequited Love: Duterte’s Embrace of China” (₱550) is published by Bughaw, an imprint of Ateneo de Manila Publishing Press.