By virtue of Proclamation no. 727, s. 2024, Feb. 25, 2025, the anniversary of the Edsa People Power Revolution, was declared a “special (working) day” by President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. The year before, Feb. 25 was not included in the list of national holidays at all, because, as per the Office of the President, it “[fell] on a Sunday” thus it “coincides with the rest day for most workers and laborers.”

Bongbong did not issue a statement regarding the day he deemed “special,” but not sufficiently so to become a national holiday. During a press conference on the day itself, Palace Press Officer Claire Castro stated that, sans a statement from the president, the designation of the day itself “means a lot,” as it encourages people to commemorate the “Edsa People Power” if they feel the need to. None of the journalists present asked if that meant that some people who wanted to participate in commemorative activities would have to miss work to do so.

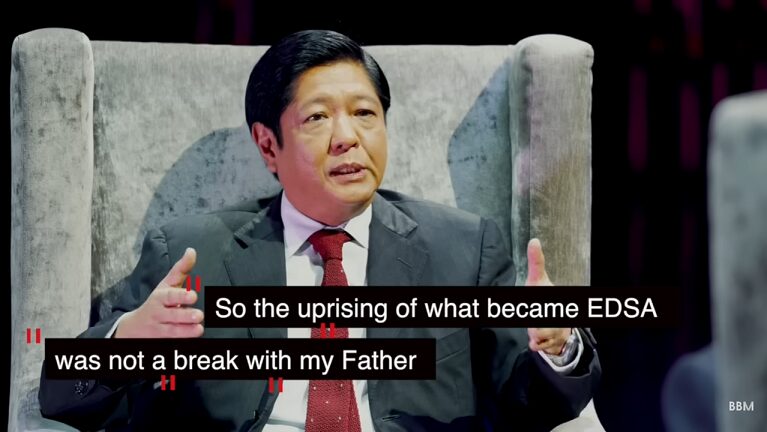

Of course, it is perfectly understandable why the president does not consistently value the Edsa revolution. Bongbong had spoken about the events of February 1986 many times before, seemingly alternating between conciliatory and hostile, but most of the time, he has been dismissive of the events that led to his father’s ouster and their family’s exile. For decades, Bongbong has insisted that their departure from Malacañang was a tactical retreat, and not because civilians—each one occupying a few square feet of open public street, unprotected by either arms or armor—were eliminating their chances of military victory.

While in exile

In 1989, before returning from the United States and reinserting himself into Philippine politics, Bongbong already had plenty to say about the People Power revolution. Only that he, like other members of his family, refused to call it “people power,” or even a revolution. In interview footage taken before Marcos Sr. died (but uploaded to YouTube only in June 2022 by the family of Arturo Aruiza, a close Marcos aide), thirty-something year-old Bongbong said,

“It [Edsa] was very well done, very well organized; I’m sure there was a core group in that who believed there were mistakes in my father’s administration for which I’m sure people were hurt, but I do not think, and I didn’t think then and I do not think now, that that was representative of the majority of the 54 million Filipinos then, I still don’t think so. . . . First of all there was no revolution, I never saw a revolution, we left because we did not want to kill fellow Filipinos. We left the Palace to go to Ilocos. We were tricked into coming to Hawaii. And I don’t see in that revolution, I cannot see how it constitutes a revolution.” (underlining added)

Bongbong also mused, “I think what happened in ’86 was a failure of the American system. I think there were personalities or cliques within the system that decided at some point to put us away.” He called Edsa a mistake of both the United States and the Philippines. He also asserted, a little over three years after they left the Philippines in dire economic straits: “The plight of the average Filipino has worsened. . . . Life is harder, people are going hungry. The communist insurgency grows worse by the day no matter what they say. Peace and order in the cities, in the countryside is getting worse.” Never mind that people were already going hungry and had difficulty accessing basic necessities well before 1986 (with claims of rice self-sufficiency being false); that the NPA was already growing significantly before Marcos was deposed; and there were already peace and order issues and unrest nationwide, highlighted during the 1986 snap elections.

Much of this was a reiteration of claims made by or for Ferdinand Sr. before he died, as can be read in part of the introduction to his last book, A Trilogy on the Transformation of Philippine Society, and an aide memoire sent to Ronald Reagan, both of which can be downloaded from the website of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. Neither of these Marcos writings make any mention of civilians being on Edsa at all (or of the civil disobedience campaigns around the country at the same time as the revolt); the aide memoire states that the revolution “was not actually a revolution,” as it was “a restoration – the reinstatement of the old oligarchy that Marcos in the course of his ‘democratic revolution’ [an almost thirteen-and-a-half-year period] was about to totally dismantle when he was kidnaped to Hawaii on orders of Ambassador S. Bosworth and Madame C. Aquino.”

It is unclear whether the footage of Bongbong’s 1989 interview was ever distributed (as per the video’s description on YouTube, it is from “Colonel Arturo Aruiza’s private collection of videos”). The public certainly heard him when he delivered his eulogy to his father during a burial ceremony held in October 1989. As described by the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Bongbong claimed that “‘alien forces’ [i.e., the United States] who did not understand [Ferdinand Sr.] pressured the former president to leave his country.”

Return to the Philippines

Two years later, Bongbong sounded much more conciliatory when he returned to the Philippines. In a news conference on October 31, 1991, Bongbong characterized the Edsa revolt, presumably, as a “time for bitterness and anger” that, a little over five years later, was for him ancient history. “It’s a long, long time since my father died and that is over, that is over, it’s time to move on, and, if we get stuck in the past, nothing will happen to us, and it will lead us nowhere; it’s finished. It’s time to move on.”

Not long after, Bongbong launched his candidacy to become representative of the 2nd District of Ilocos Norte. Bongbong won, becoming the first Marcos to hold elected office after their family’s ouster. In his first term in Congress, Bongbong’s legislative track record was lackluster. Still, in 1995, after only one term in the House, Bongbong tried to win a seat in the Senate. In the run up to his campaign, Marcos made himself available to media outlets looking to feature an ousted dictator’s son gunning for higher office with a seemingly realistic chance of winning.

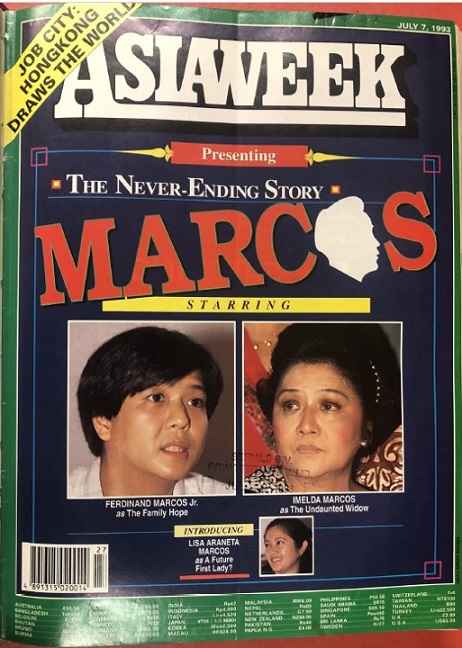

Among the international outlets that featured Bongbong between 1992 and 1995 was Asiaweek. The news magazine’s July 7, 1993 featured Bongbong (“the Family Hope”), Imelda (“the Undaunted Widow”), and Liza Araneta Marcos (“A Future First Lady?”) on the cover, as players in “the Never-Ending Story” of the Marcoses. Marcos Sr.’s remains by then had yet to be repatriated. But Marcos Jr. was already saying “[if] it happens, it happens” about becoming president in the 21st century. Bongbong also said, “All the problems I left as governor in 1986 remain”—an odd indictment, given that he was notorious for being an absentee governor from 1983 until the revolt; he had succeeded his paternal aunt Elizabeth Marcos-Keon, who was governor for about twelve years; and the governor since 1988 was, at the time, a close ally of the Marcoses, Rudy Fariñas.

To Asiaweek’s international readership, Marcos claimed that they “would have wiped out” the rebels during the February revolt, as they had 10,000 men in Malacañang. Again, no mention is made of people who were helping to protect those rebels or turn away pro-Marcos forces using nonviolent action.

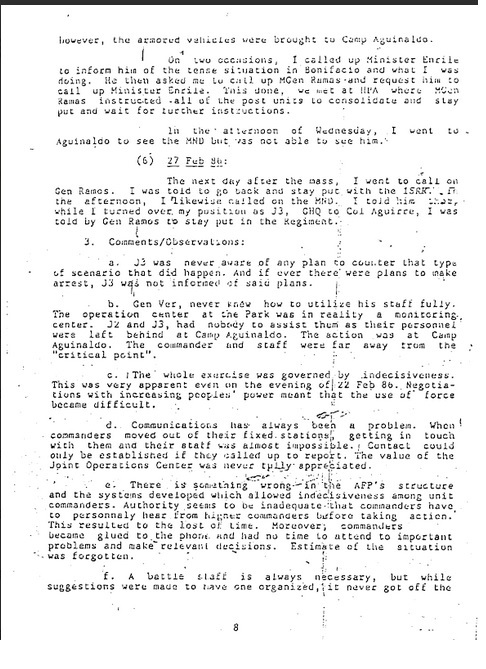

Moreover, some military sources say something else about the Malacañang forces’ ability to mount successful counterattacks against rebel forces. Dated March 5, 1986, the After Operations Report of Felix A. Brawner Jr., Commanding General of the First Scout Ranger Regiment of the Philippine Army—and uncle of current AFP Chief of Staff Romeo Brawner Jr.—noted that all the forces at Malacañang had was effectively only a “monitoring center,” and that AFP chief General Fabian Ver “never knew how to utilize his staff fully.” The communications system was “a problem,” he continued, and there was something wrong in the AFP’s structure and the systems developed which allowed indecisiveness among unit commanders.” Aruiza, in his book Ferdinand E. Marcos: Malacañang to Makiki, agreed with this assessment; he believed that they could have “routed the enemy quickly, if decisive action had been taken at once,” were it not for “so many things” that they needed to contend with, such as a sick commander-in-chief, besides Ver’s ineptitude.

In September 1993, Ferdinand Sr.’s remains were brought back to the Philippines. Bongbong had an opportunity to deliver another eulogy; as reported by the Associated Press, regarding his father’s ouster, Bongbong said, “He never could have imagined the depth which the ambitious and power-hungry would sink.” “These conspirators,” he continued, “perfected their pact with the devils, compromising the country for their personal desires.”

1995: Candidate for senator

Devils were once more referenced in the much-ballyhooed interview with Kris Aquino, youngest child of Marcos Sr.’s chief rival Ninoy Aquino and former president Cory Aquino, and Bongbong in January 1995, for the talk show Actually….’Yun Na! “Kulang na lang isipin ko na may horns kayo sa ulo,” Kris quipped, describing how she viewed the Marcoses as a child, as she understood then that “the reason [her] dad was in jail was because of [Bongbong’s] dad.” When prompted by Kris to discuss if EDSA and their exile brought the Marcos family closer, Bongbong said, “naging malapit kami,” noting that his sisters were able to devote more time to their children. When asked if he hated the Aquinos back then, Bongbong shook his head while smiling. Bongbong claimed that he accepted their fate: “Ganun talaga ang buhay, wala kang magagawa, just get on with it.” When asked regarding rumors of his political ambitions, Bongbong used Kris’s program to confirm to the nation that he was gunning for a senate seat.

Media accounts of Bongbong’s first senate run paint him as a pleasant and patient campaigner, spreading, as he would once more in 2022, the gospel of unity and nationalism. A May 1995 San Francisco Examiner article quoted him as saying, “Filipinos should love one another and take care of one another, and take care of our country”; “We should be together as one, not fighting one another to benefit foreigners.” The interview with Kris, and the fact that he was running in the same coalition as Gringo Honasan, one of the most prominent Reform the Armed Forces Movement soldiers who wanted to oust Marcos in 1986, seemed to cover what candidate Marcos Jr. needed to say about Edsa. Cory Aquino, leading what was called the Never Again Movement, campaigned against both Bongbong and Gringo, as well as congressional candidate Imelda Marcos and senatorial reelectionist Juan Ponce Enrile, who had already been singing praises to the Marcoses again, after playing a crucial role in ousting them, well before Cory’s presidency ended in 1992.

Bongbong lost in 1995, and between then and 1998, he became more preoccupied with his assertion that he was cheated of a senate seat, as well as the cases against him and his family. At the time, his mother Imelda was the most vocal member of their family regarding EDSA. On August 25, 1997, as representative of the 1st District of Leyte, she gave a privilege speech titled, “President Ferdinand E. Marcos, the True Democrat and Cory Aquino, the Real Dictator.” Imelda stated that Cory “usurped the presidency without the legal basis of a proclamation of votes by the National Assembly as provided for by the Constitution”; claimed that her husband proclaimed martial law “for the survival of the country and democracy”; and derided the “so-called EDSA revolution” as “the revolt of the oligarchy, the feudal lords, Cardinal Sin, some card-bearing communists, foreign interventionists and opportunists.” “Now as history clearly unfolds,” she added, “EDSA was the revolution against the Filipino People and the Republic of the Philippines.”

1998-2010: Governor and Representative of Ilocos Norte

In 1998, Bongbong became governor of Ilocos Norte, remaining in that position until 2007. From 2007 until 2010, he was once again representative of the 2nd District of Ilocos Norte. Within those twelve years, Bongbong did have occasion (during press briefings, for instance) to talk about the Marcos years and the revolution. In February 2000, he professed indifference toward Edsa commemoration activities. Philippine Daily Inquirer reporter Cristina Azardon claimed that Bongbong called the “collective voice of people who gathered at Edsa in 1986 as ‘white noise’;” Bongbong said he was misquoted. Bongbong apparently did not have any issue with being quoted as saying that his family had “no involvement in the designation of the date” of the Edsa revolution holiday: “We don’t know what it is that they consider to be the turning point, or the moment of triumph, or whatever it is that they sought.”

Governor Bongbong would repeatedly express such passive aggressiveness when asked about commemorating the revolution. In February 2004, Inquirer reporter Azardon noted that there was “No Edsa Day in Marcos Country.” Bongbong held several meetings on Feb. 25, 2004 even if then President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo declared that date a non-working holiday. He told reporters that “‘Before today was declared a holiday, we had scheduled several meetings. We just had to push through with them.’” Regarding the revolt, Bongbong said, “‘It is not appropriate for me to speak about Edsa.’” In February 2005, during his third consecutive term as governor, Azardon again noted that there was “No Edsa Holiday in Marcos Country.” “‘It’s business as usual,’” Bongbong said, adding, “The others can go on holiday. I don’t see anything to celebrate in the province.’” His provincial administrator Irineo Martinez confirmed that Feb. 25 was always a working day in the provincial capitol.

In between, Marcos talked about the revolt outside of press conferences. In a puff piece published in the Sunday Inquirer Magazine in May 2002, Bongbong described how surprising Edsa was: “‘I heard about government takeovers, but they only happened in other places. This one was happening to us!” The piece paints Bongbong as a highly capable leader who distinguishes himself from what he calls “political scoundrels” of the immediate post-Edsa Dos era. In the 2003 documentary Imelda by Ramona Diaz, Bongbong also expressed surprise regarding Edsa, but reiterated that it was basically plotted by the United States: “The Americans—that was the downfall. We would never have been removed from the Palace if not for the Americans. We were all shocked when the decision came that we would leave. We never thought my father would give that order.” Bongbong continued to deny that the Filipino people had anything to do with their ouster; in January 2004, he was quoted as saying, “The public never believed the things they said about us. They recognized it for what it was—propaganda.”

Propaganda, specifically the online variety, was something the family was getting into by that time as well. In 2002, the Marcoses put up the now defunct Marcos Presidential Center website. In a May 2002 press briefing, Bongbong said that the website was his sister Imee’s idea. Though Bongbong claimed that the website was supposed to show both “good and bad” information about Ferdinand Sr., there is no version of the website accessible via the Internet Archive that contains the latter. One can find across all versions a timeline that ends thusly: “Faced with a choice between unleashing the military might to crush the crowds supporting the Enrile-Ramos ‘rebellion’ on EDSA and exercising a statesman’s restraint, Pres. Marcos choose the latter. Eventually, to avert bloodshed, he gives up power and goes into forced exile in Hawaii.”

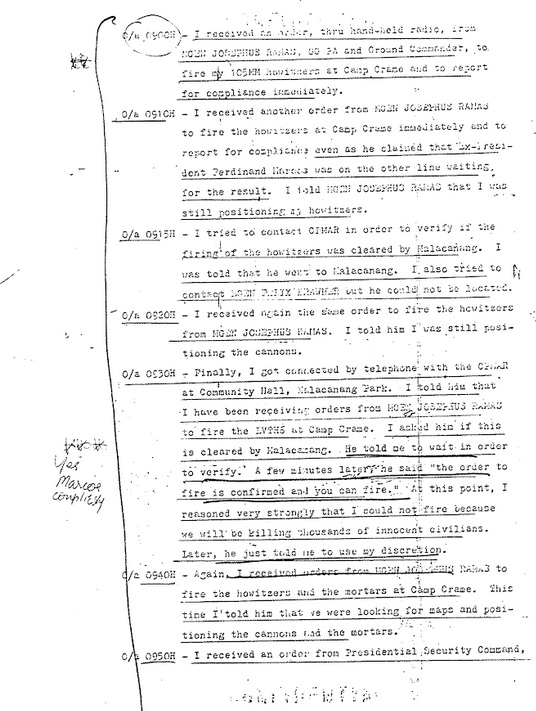

The “Participation Report” of Braulio Balbas, then Deputy Commandant of the Philippine Marines, states that at 9:00 a.m. on February 23, 1986, he received an order from Major General Josephus Ramas to fire howitzers at Camp Crame; ten minutes later, Ramas called again, saying that Marcos Sr. was “on the other line waiting for the result.” Braulio said he was still “positioning the cannons.” He then received confirmation that the order was cleared by Malacanang at 9:30 a.m. and received orders to fire again from Ramas and Irwin Ver of the Presidential Security Command within the next twenty minutes. Balbas refused to fire; he stated that “when I saw how many people were fearlessly throwing themselves along the paths of the tanks and trucks, I know that only an insane military commander would order his troops to train their guns at those hapless civilians.” According to Aruiza in Malacañang to Makiki, Marcos gave direct orders to Gen. Prospero Olivas and Alfredo Lim, telling the former to “control the crowd at EDSA” and the latter to “disperse the crowd.” Neither complied. Both Marcos Sr. and Jr. wanted a firefight; the crowds and defectors didn’t.

In 2005, Bongbong had an opportunity to return to Hawaii to formalize a sister state-province agreement between Hawaii and Ilocos Norte, as well as to make a court appearance. In an interview with the Honolulu Star-Bulletin in 2006, the year before his final term as governor ended, he said, “‘It was a very dramatic time for us in 1986.” He emphasized that claims about corruption and torture during his father’s time was “a matter of opinion,” and reinforced his ties with the significant Ilocano population of Hawaii. He also affirmed that he would stay in politics “‘for a while yet’” because he “‘[didn’t] know how to do anything else.’”

Rise to the national stage

During his return stint as a member of the House between 2007-2010, Bongbong became a candidate for senator. He had by then joined his father’s pre-dictatorship party, the Nacionalista Party, cutting ties with his father’s dictatorship-era vehicle Kilusang Bagong Lipunan, running as a “guest candidate” in the NP slate. Perhaps because he was in a coalition running against another headed by Cory and Ninoy Aquino’s son, then Sen. Noynoy Aquino—who asserted that he would continue to run after the Marcos’s ill-gotten wealth and that Marcos Sr. was undeserving of a hero’s burial—Bongbong had to deal with the legacy of Edsa more directly in 2010 than in 1995.

“Bigo ang Edsa 1!” he declared during “Edsa week” in February 2010, adding, “Lumala lamang ang kahirapan at hindi nagawang linisin sa katiwalian ang burukrasya ng pamahalaan. . . . Sa ilalim ng dating pamahalaang Marcos, higit na may direksyon ang gobyerno nito. May malinaw na programa at plataporma ang pamahalaang Marcos.” While being interviewed in March 2010 for the program Bandila, Bongbong tried to seem dismissive again, saying that they only observe the celebrations, going on with their work because “kami naman ay di kasama sa pagdiriwang na yan.” Bongbong tried to show off other sides to him besides being a Marcos scion—ranging from claiming credit for the windmills of Ilocos Norte to his musicianship—but the Edsa revolt continued to hound him.

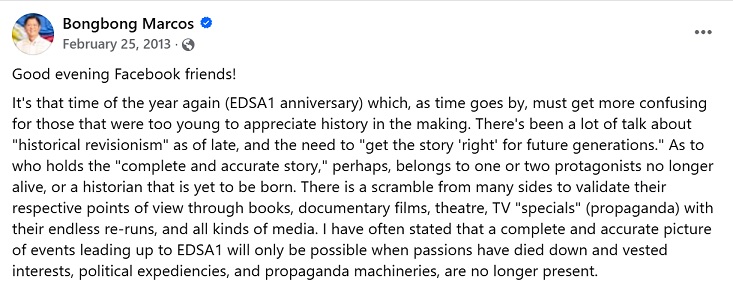

Winning a senate seat under a second Aquino administration, he did not buckle down on his reassertions regarding Edsa and his father’s legacy. In an interview with Agence France-Presse, released on May 19, 2010, Bongbong said, “To compare between him and the presidents since, [Ferdinand Sr.] was a much better president than they have been,” and that “The EDSA revolution was American-inspired,” a “regime change” brought about by foreign intervention; he felt gratified “that other people have come around to that way of thinking.” Less than a year in office later, on Feb. 22, 2011, Sen. Bongbong said that the Philippines could have been Singapore if his father was not ousted; celebrating Edsa served only to “remind us how much works need to be done and how much harder we have to work to gain that progress.” “I think that the propaganda that was so rife in 1986 has been proven to be propaganda,” he told Al Jazeera in the same year. In 2012 and 2013, he took to posting, at length, very similar claims on his Facebook page during Edsa anniversaries. He seemed constantly on the defensive, what with the Noynoy Aquino administration’s denial of the burial of his father’s remains in the Libingan ng mga Bayani, as well as the passage of the Human Rights Victims Reparation and Recognition Act of 2013 on the 27th anniversary of the People Power revolution.

Bongbong did not participate in any deliberations or voting regarding the Human Rights Victims Reparation and Recognition law.

In 2013, perhaps in response to the announcement that the Presidential Commission on Good Government planned to exhibit the jewelry seized from Imelda Marcos, the administrator of Bongbong’s Facebook page posted, “There they go again vilifying and traducing the Marcoses as if everything they own were ill gotten even if the former President was a highly successful lawyer before he became President and had invested his money wisely” (a claim contrary to what courts around the world have reiterated); Edsa was called “one big ‘panloloko’” and the “mother of all scams” “where the people were promised a better life and government reforms but instead, saw the new ‘dispensation’ use their positions to enrich themselves while continuing to blame everything on the Marcoses.”

Bongbong and his propagandists generally did not let up on such criticism about Edsa throughout the 2010s. It appeared that he took to heart the March 2010 conferment of leadership by “Marcos forces” (including former ministers of his father such as Cesar Virata and Conrado Estrella, grandson of Bongbong’s agrarian reform secretary Conrado Estrella III). Bongbong also seemed to more openly make claims about what his role during Edsa was. In a 2013 interview with Lourd de Veyra and Jun Sabayton for the TV5 program Wasak, Bongbong said, “Ang depensa ng Palasyo iniwan sa akin nung matanda, kasi sabi niya hindi na tayo nakakatiyak kung sino ang mapagkakatiwalaan dito.” When asked about being in the Senate with those in the opposite side during 1986 (i.e., Honasan and Enrile), Bongbong said they reminisced like old veterans who had long gotten rid of any enmity. (While campaigning in Ilocandia in 2004 with then presidential candidate Fernando Poe Jr. and the Marcoses, Enrile apologized to the Ilocanos for his role in ousting Bongbong’s father.)

In a 2015 interview with BizNews Asia, Bongbong remembered that he told his father, “Dad, the enemy is already on war footing, yet, you are still on peace footing. We have to get on a war footing and fight.” Echoing Imelda’s claims, Ferdinand Sr. supposedly admonished him by saying, “How many people will get hurt?” or “I have spent my entire life defending Filipinos, all my entire life was defending Filipinos, now I will kill them?”

That was the same Marcos who was president when famine in Negros, attributable to market interventions made by top Marcos crony Roberto Benedicto, led to numerous deaths, including those of minors; and whose administration had a track record of killing protestors, from those demonstrating close to Malacañang to those protesting in connection with the Negros famine.

During his 2016 attempt to win the vice presidency, though apparently intending to be fairly non-polarizing, emphasizing his achievements and plans, journalists kept asking Bongbong about his opinion on Edsa. “History,” he called it during a January 2016 “Kapihan sa Senado.” Rappler characterized the following statement as Bongbong calling Edsa a “disruption”: “‘Mahirap akong magsabi dahil ako nasa kabilang barikada nung EDSA. Ang sinasabi ko, maraming hindi natapos na tatapusin sana noong 1986.’” Bongbong was also quoted as saying, “It is unfortunate to see that if you look at objective measures, instead of progressing, we have regressed in many, many ways since 1986.” He tried to preemptively address the issue before campaigning officially started, saying via a press release that he expected Edsa celebrations to be “more intensive” because he was running for vice president—not mainly because it was the revolution’s 30th anniversary. He asserted that there were more pressing issues, and that people did not ask him about it when he “[went] around and [met] with our people.”

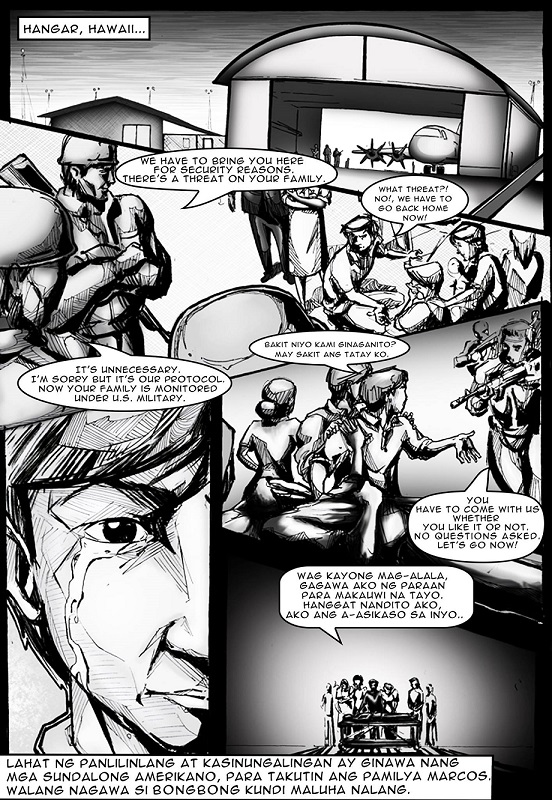

Even earlier, Bongbong’s campaign team made an attempt to address Edsa in the komiks that were uploaded online in Nov. 2015 and later distributed in print form. The pages dealing with Edsa do not show any people massing up against them, or even make reference to soldiers turning their backs on the Marcoses; all that is portrayed are Americans tricking them into flying out of the country. A panel shows Bongbong with tears streaming down his cheek: “Lahat ng panlilinlang at kasinungalingan ay ginawa nang mga sundalong Amerikano, para takutin ang Pamilya Marcos. Walang nagawa si Bongbong kundi maluha nalang [sic].”

Road to the presidency

Bongbong did not become vice president. While devoting a lot of time to protesting the election results, Bongbong also found the time to start a career as a vlogger. In 2018, in time for the anniversary of the declaration of martial law, his YouTube channel uploaded the two-parter “Enrile: An Eyewitness to History,” featuring a tête-à-tête in an empty auditorium between Enrile and Bongbong. Episode 2 was mainly about the revolution. Most of it was a reiteration of what Bongbong had previously said, and what Enrile stated in his 2012 autobiography, including the reiteration that Marcos Sr. should be praised for supposedly choosing to avoid bloodshed to prevent civil war. A key difference: both Bongbong and Enrile insisted that in retrospect, had Marcos Sr. wanted to, Enrile’s forces really would have been decimated, and any attack on Malacañang would have ended with a Marcos win—“we were very well-prepared,” said Bongbong. But Enrile noted in his biography that by day three of the revolt, military defections to the anti-Marcos side had accelerated, morale among Marcos’s men was very low, “Some of the commanders of President Marcos could no longer control their men,” and that before the Marcoses left, “his [palace] guards had left their posts.”

Thus, by the time it became increasingly clear that Bongbong would run for president in 2022, he had repeatedly attempted to establish himself as an active palace defender during the revolt, a would-be fighter on the pro-Marcos side who, as early as the 1990s, had already reconciled with the military forces intent on deposing his father in 1986—based on this narrative, unity among the only Filipino Edsa actors who mattered to him had already been achieved. What to do still about those who supposedly were merely swayed by opportunistic elites and the United States? He was able to avoid talking about Edsa during his 2022 presidential campaign by hardly giving interviews or participating in debates. No more interview-with-Kris gimmickry nor aggressive counterpoints to Cory or Noynoy Aquino (who died in 2021)—the claim that Edsa was merely a ploy of Aquino-led oligarchs worked in his favor, as there were no more Aquinos in play.

In his 2023 statement about the revolution (without calling it such), Bongbong had this to say: “As we look back to a time in our history that divided the Filipino people, I am one with the nation in remembering those times of tribulation and how we came out of them united and stronger as a nation.” Marcos spoke of the event as if it were a tragedy, and as if to heal the trauma it caused, he offered his “hand of reconciliation to those with different political persuasions to come together as one in forging a better society — one that will pursue progress and peace and a better life for all Filipinos.” This after decades of mostly towing the divisive family line: there were no “people” in the People Power revolution, only a coup that involved a few who were fooled into becoming the Marcoses’ persecutors.

His immediate predecessor’s last People Power anniversary statement begged to differ: “It has been 36 years, but the events of the People Power Revolution remain vivid in our memory, when millions of Filipinos gathered at EDSA to reclaim our nation’s democracy,” says former president Rodrigo Duterte’s 2022 statement; “As we honor the courage and solidarity of those who have come before us and fought to uphold our democracy, let us honor and thank those who continue to keep alive the legacy of this largely peaceful and non-violent revolution.”

Despite the hollow hallelujahs from a former killer-in-chief—and recently, his equally trigger-happy offspring—and the lies and telling silences of a kleptocrat’s son, if the turnout of the protests on Feb. 25 this year is any indication, People Power—truthfully against tyranny and dictatorship—is still alive. And it is stirring.

*Miguel Paolo P. Reyes is a University Research Associate at the Third World Studies Center (TWSC), College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman, and a senior lecturer at the same university’s Department of English and Comparative Literature. Joel Ariate Jr. provided research assistance for this article. This piece is part of TWSC’s ongoing Marcos Regime Research program.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.