By DESIREE CALUZA

Photos by MARIO IGNACIO

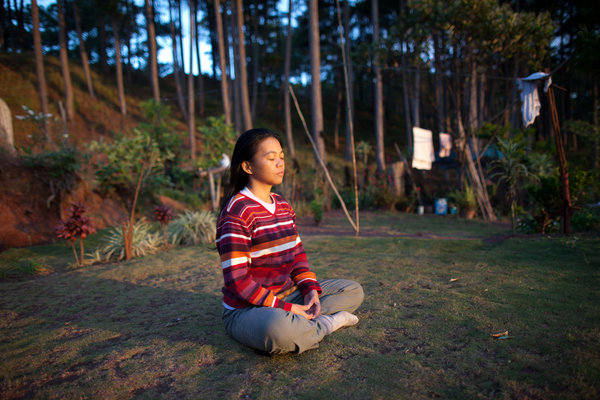

SAGADA, Mt. Province —Morning has broken and the sun casts its rays on this northern highland village as a widow sings a song of peace for those whose hearts have been pained by turmoil and violence.

In Sitio Nadatngan in Barangay Madongo here, Florence “Dom-an” Macagne Manegdeg, who turns 39 today, greets the day facing the sun and accompanying its ascent in the horizon by playing her bamboo flute.

This has been a daily ritual: her first act of the day a prayer for peace and healing.

The mountains of Sagada have been a refuge for Manegdeg, whose husband was one of the hundreds of activists killed while Gloria Macapagal Arroyo was president. Jose “Pepe” Manegdeg, a father of two, was only 37 when unidentified men shot him by the roadside in San Esteban, Ilocos Sur on November 28, 2005. He was, at that time, the coordinator of the Rural Missionaries in the Philippines in the Cordillera and Ilocos. To this day, the case remains unsolved.

“I have gone through so much violence in my life, and I have already reached the tipping point and I cannot be the person who should go on life agonizing,” Manegdeg said.

In 2010, Manegdeg turned her home in this farming village into a center for peace and healing, and called it “Kasiyana.”

Kasiyana is a powerful word in the dialect of the Kankanaey, the one of the tribes that inhabit the Cordillera region, and to which Manegdeg belongs. It refers to the belief that in times of pain or uncertainty, a threefold process happens: a recognition of pain and difficulty followed by hope and finally by loving action.

Manegdeg’s home is now known as the Kasiyana Peace and Healing Center, a respite for individuals who have experienced trauma and a center for those who are advocating and volunteering for peace and healing programs.

Manegdeg said the center is not a typical institution with rooms and facilities. The center is the house itself, which she and Pepe built for their family before he died.

The two-storey house is made of pinewood and is surrounded by vegetable and fruit gardens, set against the backdrop of the lush pine forest and rice terraces beyond.

“This place is a home where one can experience the serenity of nature. It is modeled after the concept of bahay kubo (nipa hut); it’s all about finding happiness in simple living and appreciating the gifts of nature. Pepe envisioned this as a sanctuary,” said Manegdeg.

A space for healing an activism

The house is 15 minutes’ walk down a trail of pine trees and wild berries from the village center of Sagada.

Manegdeg’s maternal parents inherited the land on which the center sits from her great grandfather who reclaimed it after World War II, when the place became a civilian evacuation center. Sagada, with a population of 10,000, is one of the most popular towns in the northern upland region called the Cordilleras.

The Manegdeg couple started building the house in 2003. A year after Pepe died, Manegdeg, with the help of family and friends, conceptualized the Kasiyana Peace and Healing Initiatives. And four years after, on May 22, 2010, launched it as a peace and healing center.

The group who formed it engages in dialogues, advocacy and networking, research and documentation of traditional and contemporary bio-socio-psycho-spiritual healing, sustainable practices in environment and resource management, conflict transformation and restorative justice. The center prioritizes women, widows and children who have undergone trauma.

During the healing process, there is a lot to learn in Kasiyana. The center offers workshops in organic farming, art and music (including bamboo nose flute playing), meditation, tai chi and yoga.

“This is part of the healing journey, this is a place where you can reintegrate with the community. This is a peace center, and not a family property. The community is involved, the villagers understand the people who come here; they are here to seek for sanctuary. This is a community-based healing,” Manegdeg said.

Love and peace in the sacred hills

Manegdeg grew up in a mining community in Lepanto Mines in Mankayan, Benguet. As the second child in a brood of six, she was closest to her elder brother who taught her how to play the nose flute.

“I was attracted to the state of peacefulness whenever I played the flute,” she said.

Manegdeg’s father worked as an underground miner. Their life in the mining community was one of poverty.

“We had no electricity and water supply,” she said.

In 1992, she met Pepe, a native of Pagudpud, Ilocos Norte at a church gathering for the youth in Baguio.

“He fell in love with me because I played the bamboo nose flute well. When I met Pepe, he was to me a brother, a comrade and a friend, and he told me that I was going to be the mother of his children,” she fondly recalled.

Pepe was a gentleman with a wound of his own that he carried throughout his childhood, said his friend Fr. Jerry Sagayo, former parish priest of Sagada.

“One of the most tragic things in life was the death of his father. His father was killed due to a political conflict in Ilocos. For a time, it affected his speech because the violent death shocked him. I have always known Pepe as a gentle person, a loving husband to Dom-an and his children and a good son to his parents and his in-laws,” Sagayo recounted.

Manegdeg said Pepe once told her that he wanted to avenge his father’s death but his attitude changed when they got married in 1996. “He was excited to become a father because he missed his father so much, he would even buy baby books and other baby stuff even though we did not have a child yet,” she said.

But Manegdeg had her own share of tragedies, even before Pepe was murdered, having lost two brothers in separate stabbing incidents.

In November 2000, her 23-year-old brother Michael was stabbed in an altercation with a taxi driver in Baguio City. Four months later, her 15-year-old brother, Bertrand Paul, was also stabbed by another teenager in a dispute over a ballpen in Mankayan town in Benguet.

“These are senseless killings, but we invoke kasiyana, we will get over this, and we told ourselves not to be dragged into the violence that was committed to us,” she said.

Starting anew

It was after the tragic death of her two brothers that the Manegdegs decided to build a house in Barangay Nangatdan in 2003.

With a small budget of P15,000, the house was constructed and the elders conducted a ritual called “sangbo” which means indigenous house blessing. A local rice cake called “binaod,” which symbolizes unity and celebration, were served to mark the family’s return.

Manegdeg’s parents relocated to Sagada in 2004 to recover from the death of their two sons.

The Manegdeg couple planted 10 lemon trees to start their “sanctuary.”

“We were talking about starting a new life, we wanted to form a core of farmers to start organic farming in the village. We were also talking about retiring from activist work but activism has enriched our lives, we always talked about pursuing human rights and social justice,” Manegdeg said.

Pepe’s work in Ilocos, wherein he trained farmers on rural development, had also inspired him to be a farmer in his new home in Sagada. An Ilocano native, he had endeared himself to the community of Nadatngan where he established his family while working as a coordinator for a church organization in Ilocos.

After Pepe’s murder, Manegdeg and her two daughters had to flee to Manila in 2006 and sought sanctuary among nuns in Tagaytay in 2007. She and her daughters Andrea Nikole and Geraldine Kate returned to Sagada only in 2008 to establish the center.

“When Pepe died, I lost a partner, but we both had wanted to build a sanctuary like this. There were times that I felt sad, but my aunt said, I had to continue what Pepe and I started,” Manegdeg said.

“Pepe’s physical body has died, but our dreams for this community have to continue. It would have been better if there were two hearts and two minds in this endeavor, but I am the one who is here, but I am glad that there are people who are willing to help me in this journey.”

(This story is part of the VERA Files project “Human Rights Case Watch” supported by The Asia Foundation and the United States Agency for International Development.)