By MARIA FEONA IMPERIAL

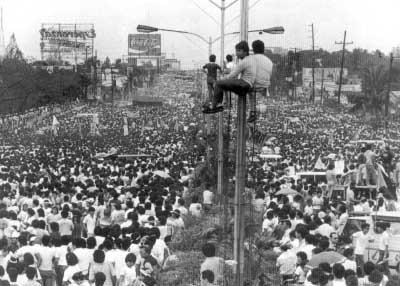

THIRTY years ago today, Filipinos reclaimed their democracy.

In 1986, a monumental shift in history was being conceived at EDSA. An oppressed collective had resolved to overturn strongman rule through a peaceful revolt that banked on the promises of freedom, liberty, peace, justice and other universal imperatives.

A revived nation, Filipinos were expected by the frontrunners of People Power to further those promises.

But they have failed—the failure being themselves, said lawyer Christian Monsod, an EDSA icon and one of the authors of the 1987 Constitution.

“What we were able to achieve at EDSA was a radical political change by bringing down a dictatorship. That’s only half of it,” Monsod told VERA Files. “(The) other half is radical change with the poor at the center of development. And we have not fulfilled that.”

Most Filipinos consider themselves poor, a blunt manifestation of the failure of government leaders to carry out the true intentions forwarded by the Constitution.

Monsod, former chairman of the Commission on Elections, and 29 other individuals and institutions were recognized Wednesday in the Kaisa ng Bayan Awards of the Simbahang Lingkod Bayan (SLB) at the Ateneo de Manila University.

Established on Feb. 25, 1986 during the People Power Revolution, SLB started as the National Citizens’ Movement for Free Elections (NAMFREL) Marines. It now advocates for voters’ education and disaster management.

The Kaisa ng Bayan Awards is first in the organization’s 30 years of existence. Awardees were chosen for their advocacies that embodied the organization’s core values of faith that does justice, genuine democracy, love for country, preferential option for the poor, and stewardship of creation.

Monsod said social justice and human development were supposed to be the end goals of EDSA 1.

But he said the Philippines, though a rising economy in Asia and worldwide, is a “laggard” when it comes to addressing poverty and social inequality.

“It should be so clear to us that we have failed. (W)hy don’t we admit it and say we have to change things?” Monsod said.

Until the estimated 24 million poor Filipinos get a chance to live decent lives, the Philippines will always fall far behind, he said.

Monsod counts himself a part of the failure. “I was part of it (government), how come I wasn’t able to change it?”

He said the ultimate measure of attaining the promises of People Power is having a new generation of leaders who know how it is to be poor.

But those who are poor and have been seduced by money “don’t deserve to be in power,” he said.

Monsod also lamented the failure to educate children on the lessons of People Power Revolution.

History textbooks lack adequate and comprehensive accounts about the events of People Power, he said.

“For people who are involved in education, why did we allow the story of EDSA to be watered down for what it really was?” he said.

Despite firsthand accounts of oppression, harassment, torture and other forms of human rights violations committed during martial law, reports say some Filipinos, most of them millennials, still yearn for the supposed “golden age” of former president Ferdinand Marcos.

The Marcos family is experiencing further political resurgence, evident in the consistent high rankings of vice presidential bet Sen. Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos in preelection surveys.

Jesuit priest Xavier Alpasa of SLB considers it a paradox: “People Power started when we toppled a dictator. Now, we find the son running.”

On the other hand, this only shows that People Power is an evolving story, Alpasa said.

The youth should not forget the lives of those who were assassinated, jailed, harassed and tortured during martial law, he added.

Young peace advocate Arizza Ann Nocum, one of the awardees, said the fascination for strongman rule is a sign of desperation of the Filipino people.

“We see that previous administrations were not effective in carrying out reforms. We think that force alone will be able to change it,” she said.

But force is not the answer, she said. One person doing the job of bringing together people from different religions, communities and provinces would not work.

“What’s lacking is a leader who’s going to bring us together,” Nocum said.

Nocum is the overall head of the Kristiyano-Islam Peace Library, a nonprofit organization that seeks to build accessible libraries in conflict-stricken areas in the country.

With the 2016 elections coinciding with the 30th anniversary of the People Power Revolution, Nocum said voters, especially the youth, should remember the lessons of EDSA.

One of the timeless gains in People Power is the value of individual heroism, she said.

“Marcos didn’t expect that people would unite enough to create a majority that had so much power that he couldn’t move his people, that he couldn’t move his soldiers,” Nocum said.

Weighing in on this year’s elections, Monsod said election workers and government leaders should address “structural problems” in the country’s elections— vote buying, dysfunctional political parties, limited choices of candidates, warlords and dynasties—beyond ensuring an accurate count of votes,

Vote buying is prevalent because election day is the only time the poor feels that they have power, particularly in choosing candidates.

“After elections, the power is somewhere else, not with them,” he said.

“Until we address these structural problems, then what we have is a form of democracy but in a very large extent is a fiction of democracy,” Monsod said.