On Quezon City’s roads, death awaits drivers as the night deepens.

If you’re one of them, your chances of dying in a road crash peak from 11 p.m. to 1 a.m., data from the Metro Manila Development Authority (MMDA) show.

Yet, in these deadliest hours, the streets are clear of traffic enforcers who can help save your lives.

From 6 a.m. to 10 p.m., traffic enforcers take turns manning the city’s busiest roads, each of them stationed at “choke points” or areas notorious for heavy traffic. Beyond these hours or when most fatal crashes happen, the roads are unguarded.

Quezon City recorded a total of 33,717 road crashes last year, the highest in Metro Manila according to the MMDA.

For the government, it’s traffic over safety. In fielding the bulk of enforcers, officials prioritize congested roads over crash-prone ones. “Our deployment depends on where there is heavy traffic, or where areas are congested,” said Glenda Lim, chief of Police Community Relations at the Philippine National Police Highway Patrol Group (PNP-HPG.)

Black spots, or areas notorious for road crashes, come secondary in traffic deployment, even as studies have shown the presence of traffic enforcers deters reckless driving behavior that results in road crashes.

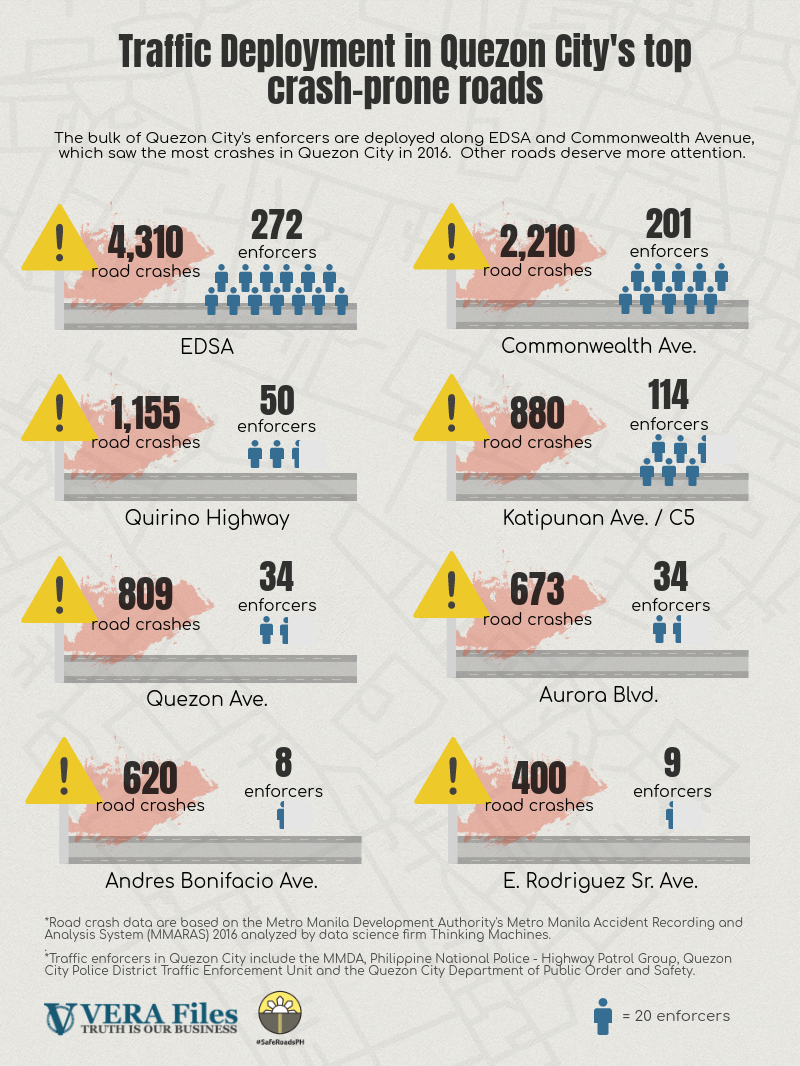

Quezon City’s deadliest roads, ranked by data science firm Thinking Machines based on the number of road crashes in 2016, are EDSA, Commonwealth Avenue, Quirino Highway, Katipunan Avenue, Quezon Avenue, Aurora Boulevard, Andres Bonifacio Avenue and E. Rodriguez, Sr. Avenue.

Of these roads, there’s a higher likelihood of enforcer response in the event of a crash in EDSA, Commonwealth and Katipunan, compared to other roads.

VERA Files, culling traffic deployment data from the MMDA, PNP-HPG, the Quezon City police and the local Department of Public Order and Safety (DPOS), ranked the city’s crash-prone roads based on enforcer to crash ratio.

The enforcer to crash ratio corresponds to the number of enforcers likely to respond to a crash on a particular road on a given day.

If a crash occurred in Katipunan Avenue, there are 47 enforcers likely to respond on a given day.

If it happened in Commonwealth Avenue, once dubbed the country’s “killer highway,” there are 33 enforcers who are likely available to assist.

In 2016, Commonwealth Avenue recorded over 2,000 crashes, the second highest in the city next to EDSA, which saw over 4,000 crashes.

Along EDSA’s various junctions from Balintawak to Santolan in Quezon City, there are some 23 enforcers who are likely to attend to you in the event of a road crash.

Notably, Katipunan, Commonwealth and EDSA are notorious for heavy traffic, thus the abundance of enforcers.

Lim of the PNP-HPG, a member of the Inter-Agency Council for Traffic, says EDSA is already “safe.” The goal, after all, is to facilitate the movement of vehicles though slow, she said.

Yet, in other roads with fewer choke points but are equally high-risk, the odds of being saved get smaller.

One’s chances of being saved may be higher in Katipunan, which has 160 percent more enforcers than in Aurora Boulevard with only 18 enforcers likely to respond on a given day.

More, the 12-kilometer Commonwealth Avenue has 100 percent more enforcers than in Quirino Highway, despite having the same length. On a given day, Quirino only has 15 enforcers who are likely available to assist.

The gap between enforcers and crashes is biggest in the case of the four-lane Andres Bonifacio Avenue, a 1.9-km road that connects the North Luzon Expressway to the southern city of Manila. There are only four enforcers who could provide help.

“That’s alarming, right? Why is the [disparity] too large?” Lim said in Filipino.

“I wouldn’t want to pass through that road anymore,” she said jokingly, admitting though that she doesn’t take the route on a regular basis.

Surprised by the shortage of enforcers on crash-prone roads such as Andres Bonifacio Avenue, Quirino Highway and Aurora Boulevard, Lim recognized the need to refocus efforts in these areas.

“There are more cases to investigate in these areas, so there should be more police officers,” Lim said. “[Motorists] may be more careful when they see traffic enforcers,” she explained.

Katipunan Ave. and Aurora Blvd. intersection in Quezon City

The relationship between road crashes and traffic law enforcement has been studied extensively.

In a book published in the United Kingdom, a chapter on the “effectiveness of traffic policing in reducing traffic crashes” found that if motorists perceive they might get caught violating road rules – by an enforcer, or tracking devices such as speed guns or CCTV cameras – they will adjust their behavior. This in turn reduces the likelihood of a road crash.

While the city’s roads are equipped with closed circuit television cameras in select areas, these cameras are used mainly for monitoring traffic situation and are not designed to capture traffic violations and road crashes in real time.

Speed guns targeting speeding vehicles are also limited in number.

In May, the World Health Organization highlighted that excessive speed is among the key behavioral risk factors for road deaths and injuries, contributing up to half of deaths from road crashes in low- and middle-income countries like the Philippines.

For its part, Lim said PNP HPG has intensified campaigns, in the form of infomercials and graphics, among others, advocating speed reduction as a safety measure.

Last year, the agency recorded a total of 32,269 road crashes in the Philippines mostly from reckless driving, or an average of 88 incidents daily. Of this number, 2,144 resulted in deaths.

Focused on Metro Manila road crashes alone, the MMDA reported a total of 109,322 incidents. In Metro Manila, Quezon City, the largest city in terms of land area, recorded the highest number of crashes.

To reduce the number of road crash deaths and injuries in the city, the local government has approved on third and final reading the Quezon City’s Road Safety Code.

The code, a signature away to becoming an ordinance, introduces interventions such as setting specific speed limits on main roads and implementing a no helmet, no travel policy.

In a news report, Vice Mayor Joy Belmonte said the local government will also deploy more traffic enforcers at night to deal with road crashes.

A Quezon City DPOS officer managing traffic flow at Commonwealth Ave. Photo courtesy of QC Public Affairs Office

Yet, for DPOS Traffic Operations Chief Dexter Cardenas, augmenting enforcement alone wouldn’t solve road crashes.

A disregard for road rules resulting in road crashes, he said, usually happens in between intersections without traffic lights or enforcers.

“In between those intersections, when a crash occurs, there are no enforcers assigned to monitor because there is no traffic congestion in those areas,” he said.

“Deploying an enforcer is not an immediate solution. Perhaps, their visibility would instill fear, but there are three approaches to [addressing road crashes],” Cardenas said, adding that education and environment are as crucial.

“Because what people see as the only solution to road crashes is enforcement, which should not be. There must also be education, teaching people to be obedient to the law. And secondly, the engineering and design of the road,” he said.

Cardenas eagerly awaits the passage of the Road Safety Code of Quezon City, which he said will now enable traffic safety officials to examine the causes of road crashes in blackspots, and evaluate the reasons behind these.

“Does the road need enforcers, or just some lane markings and certain signages? The engineering design of the network or the quality of the road surface could also be the problem,” he added.

This story was produced under the Bloomberg Initiative Global Road Safety Media Fellowship implemented by the World Health Organization, Department of Transportation and VERA Files.