By JAKE SORIANO

[metaslider id=48020]

Photos by LALA ORDENES

At first glance, the Quezon City Regional Trial Court looks more like a church than a court.

An assortment of statues — Christ on the cross, the child Jesus, the Virgin Mary — stare down on court employees, lawyers, police officers, nervous witnesses, family members of the accused or the victim, waiting for their turn to enter the court.

Behind the icons, cursive letters say, “Mother of Perpetual Help, Pray for Us,” a church altar almost, facing long benches that are arranged as if to seat a congregation.

On the right is Branch 83, a small room that can hold maybe 30 people at most, and it is here where trials continue five years on against the suspects in the 2011 road crash that killed veteran journalist and VERA Files trustee Lourdes “Chit” Estella-Simbulan.

She was on her way to the UP-Ayala Technohub when two speeding buses rammed the taxi she was in.

For her friends and family, two things this August highlight her yet-to-be-resolved court case.

On the 19th, Estella-Simbulan would have celebrated her 59th birthday.

Road safety laws

Earlier in July, a measure that could have prevented her untimely death became law. To be more exact, Republic Act 10916, or the Road Speed Limiter Act of 2016 lapsed into law, having been submitted to former President Benigno Aquino III during his final months in office.

“It’s a step in the right direction,” lawyer Sophia San Luis, executive director of Imagine Law, says. “Only 80 countries in the world have speed limiter laws and we’re now one of them.”

The law is a pro-active and pre-emptive approach to ensure the public’s safety against speed- related incidents. Only public utility buses, closed vans, haulers or cargo trailers, shuttle services, cargo trucks are required by this law to install speed limiters in their vehicles.

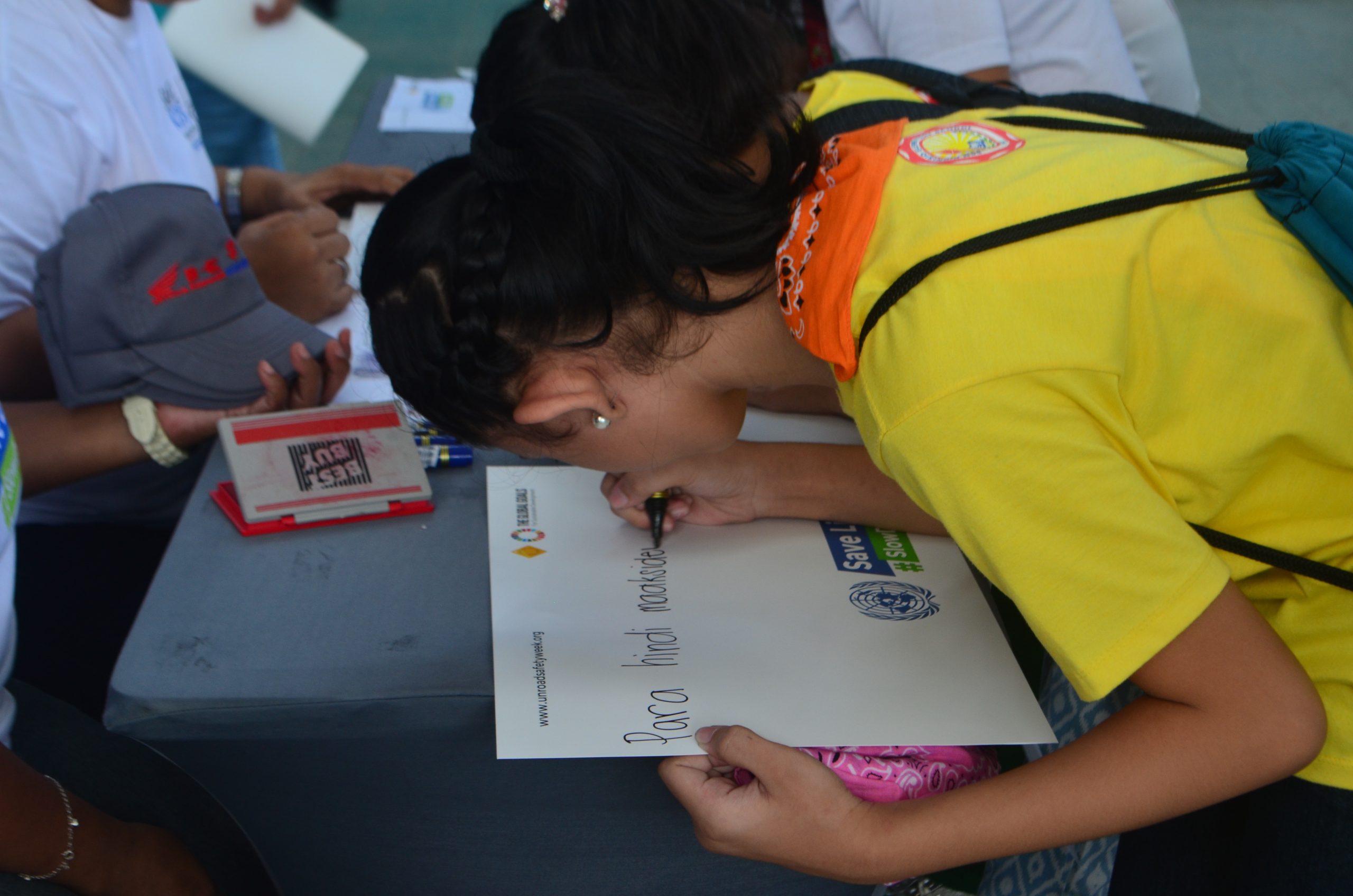

Advocates have frequently stressed road crashes are not accidents, are not to be blamed to fate or the will of God. Rather, they are highly preventable if policies and institutional mechanisms are properly in place.

On the site of the road crash that killed Estella-Simbulan, a marker has been erected and stands today, reminding drivers and commuters of Quezon City’s “unwavering commitment to make Commonwealth Avenue one of the safest thoroughfares in the Philippines.”

Despite the attention and the subsequent conservation on road safety her death has spurred, fatalities had not significantly decreased.

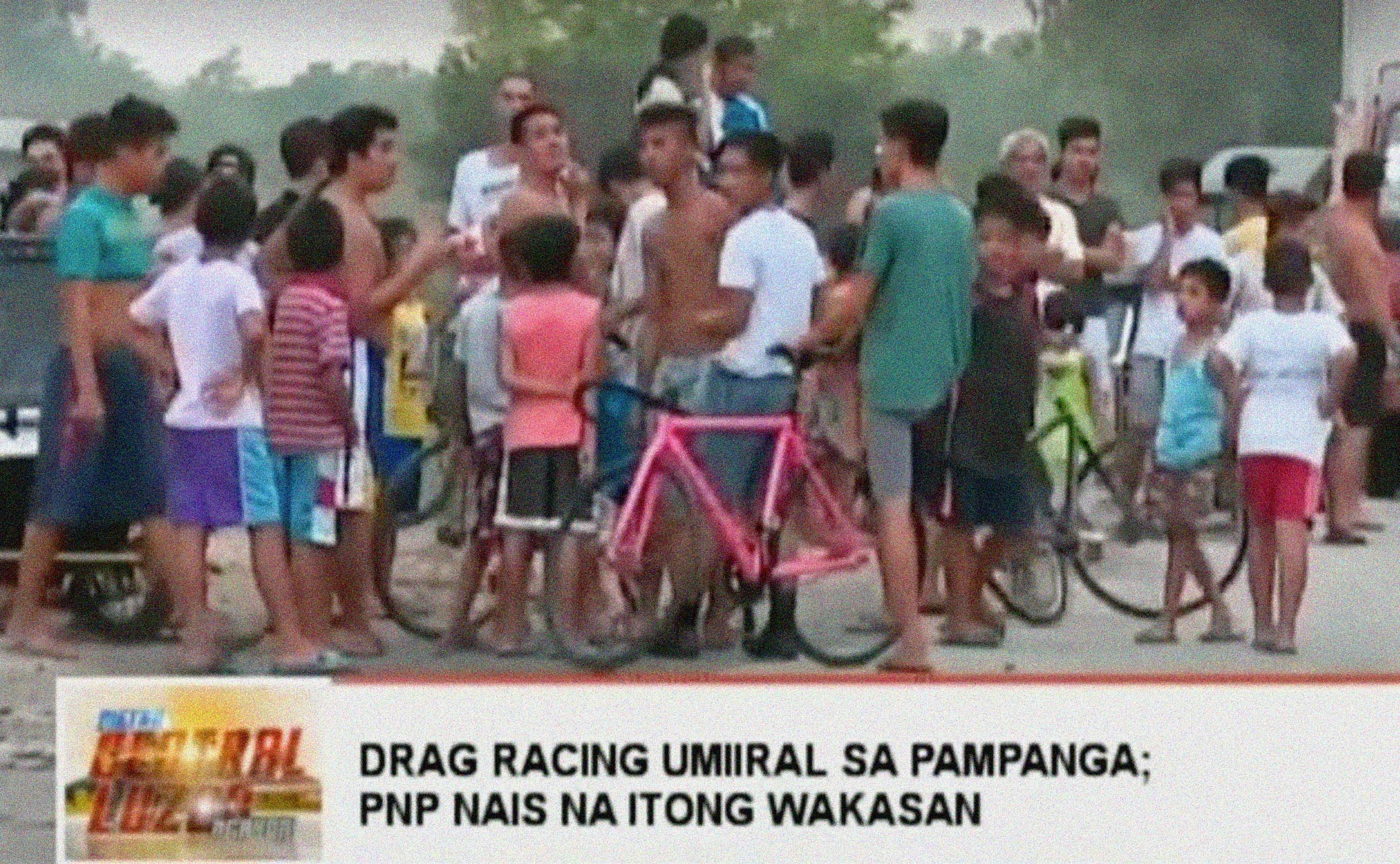

Data from the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA) show at least one person dies every day in a road crash in Metro Manila in 2015. In the same year, the Philippine National Police–Highway Patrol Group data show overspeeding as still the major culprit.

But it might take a few years before the public sees the law being fully implemented. It’s been almost a month, but the President’s office still hasn’t published the law.

Only until it has been published by the Official Gazette or in a publication with national circulation, will the law become effective, and its implementing rules and regulations or IRRs can be drafted.

“Until then, you can’t really exact compliance from the covered vehicles,” San Luis says.

And due to the technical nature of the law, it might take a while to draft the IRRs.

“The speed limiters need to be standardized and the LTO and/or LTFRB is in charge of supervising and inspecting the settings of the speed limiters to correspond to maximum allowable limits in the route of the vehicle,” lawyer Evita Ricafort, also of Imagine Law, adds. The Department of Science and Technology as well as the Department of Trade and Industry are also involved in drafting the law’s IRRs.

Another road safety law, the Anti Drunk and Drugged Driving Act of 2013 only finalized its IRR after two years, in 2015. Only then could the law enforcers implement the law.

Estella-Simbulan’s family has no plans yet for her birthday, but her sister from the U.S. has recently arrived and they have visited her crypt a few days ago, according to her nephew Gino.

The rest of the family have plans to get together on the weekend to visit her at San Agustin Church.

Five years on, her case file has become thicker and thicker with photos, affidavits, court notes but without a clear resolution in sight.

Among the contents of the case file is a supplemental complaint-affidavit executed in 2011 by Roland Simbulan.

In it, he calls “extraordinary” the circumstances of Estella-Simbulan’s “sudden, unexpected and violent death,” one that could and should have been prevented by good road safety laws.