Bobby De Mesa knew the man was dead the moment he saw the body on the street.

Back from patrolling the restaurant- and bar-filled stretch of Tomas Morato the evening of Oct. 2, De Mesa got a call from the village securityoffice and was among the first responders to the crash that killed parking attendant Celso Calacat.

“Pagdating namin doon,’yung tao nasa kalsada na. Nun palang wala na eh, patay na (When we got to the scene, he was already on the street. Even then, he was already gone, he was dead),” De Mesa said.

Calacat was helping a car back up when he was sideswiped at around 12:30 a.m. by a silver BMW driven by Isabela province board member Ed Siquian Go.

An alcohol breath test at Jose Memorial Medical Center revealed Go had been drinking, several news reports say.

Driving while intoxicated is prohibited by law, yet deaths like Calacat’s from preventable road crashes prevail due to the poor implementation of the five-year-old Anti-Drunk and Drugged Driving Law.

Two other road safety laws, the Motorcycle Helmet Act and the Road Speed Limiter Law, also face implementation woes, the House of Representatives Committee on Transportation found in a hearing Sept. 12.

Transport officials present in the hearing blamed the same culprits: conflicting pieces of legislation, a lack of deputized traffic enforcers and delays in accreditation of road safety equipment.

‘Easy’ field sobriety test

|

Law |

Issue |

|

Anti-Drunk and Drugged Driving Act |

Suspected drunk or drugged drivers pass ‘easy’ field sobriety test, rendering breath analyzer results inadmissible in court |

Under Republic Act 10586, or the Anti-Drunk and Drugged Driving Act of 2013, drivers involved in vehicular crashes leading to death or physical injury are subject to mandatory chemical tests.

However, for individuals not involved in crashes but are suspected to be driving under the influence of liquor or drugs, a “field sobriety test” is required before a law enforcement officer may conduct any chemical test.

For this reason, out of the 100 people they have accosted from Jan. 1 to June 30 suspected to be drunk-driving, not one has been penalized, said Land Transportation Office (LTO) Assistant Secretary Edgar Galvante.

“We cannot impose penalty immediately unless there is a court order that finds them guilty,” said Galvante at the hearing.

The “easy” field test, which involves drivers being made to do a one-leg stand, a walk-and-turn test and the horizontal gaze nystagmus, which tests involuntary eye movement, makes it easy for suspected drunk or drugged drivers to slip past enforcers.

“Yun pong sanay na, madali nilang maipasa angsobriety test (Those who have gotten the hang of it, they easily pass the sobriety test),” Galvante said.

“Madali nakakalusot ang nagdadrive even under theinfluence of alcohol kasi sanay na sila saquestions tungkol safield sobriety test (Drivers, even under the influence of alcohol, breeze through it because they’re already used to the questions in the field sobriety test),” he added.

Penalties for drunk and drugged driving range from a P20,000 to P80,000 fine and at least three months imprisonment if nobody was left injured or dead; imprisonment for six months to 20 years and a P100,000 to P500,000 fine if somebody was left injured or dead; and the confiscation and possible suspension of licenses.

Criminality vs road safety?

|

Law |

Issue |

|

Motorcycle Helmet Act |

Several local government units have instituted a no-helmet policy |

Two years before the crash that killed Calacat, a drunk motorist in Cavite province crashed his motorcycle on a bridge.

Francis Llabantos was coming home to Naic town after a birthday-party-cum-drinking-session with his kumpadresin General Mariano Alvarez town at around 2 a.m. sometime in October 2016.

He woke up not in his bed but at the emergency room of the Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo Memorial Hospital.

Six bottles of Emperador Light and a case of Red Horse he downed with friends took a toll; he fell asleep while driving his motorcycle along Malabon Bridge an hour into his supposed hour-and-a-half drive.

“Parang nakatulog ako. Madaling araw na rin, siguro yung paspas ng hangin, napaidlip ako(It seems I fell asleep. It was early in the morning, and possibly because of the breeze, I snoozed),” Llabantos said.

“Bale ang pagkakatanda ko lang, parang may narinig lang ako na boses na tinatanong ako kung okay pa ako. (What I only remember next is hearing a voice asking me if I was alright,),” he added.

Thanks to his P1,800-half-face-helmet, Llabantos only got a few scratches on his body and a cut on his right ear.

Others may not be as lucky, with several towns and cities in the country issuing local ordinances prohibiting the wearing of helmets, directly contradicting Republic Act 10054, or the Motorcycle Helmet Act of 2009

Under the law, the wearing of helmets is mandatory for all motorcycle drivers and riders “while driving, whether long or short drives, in any type of road and highway.”

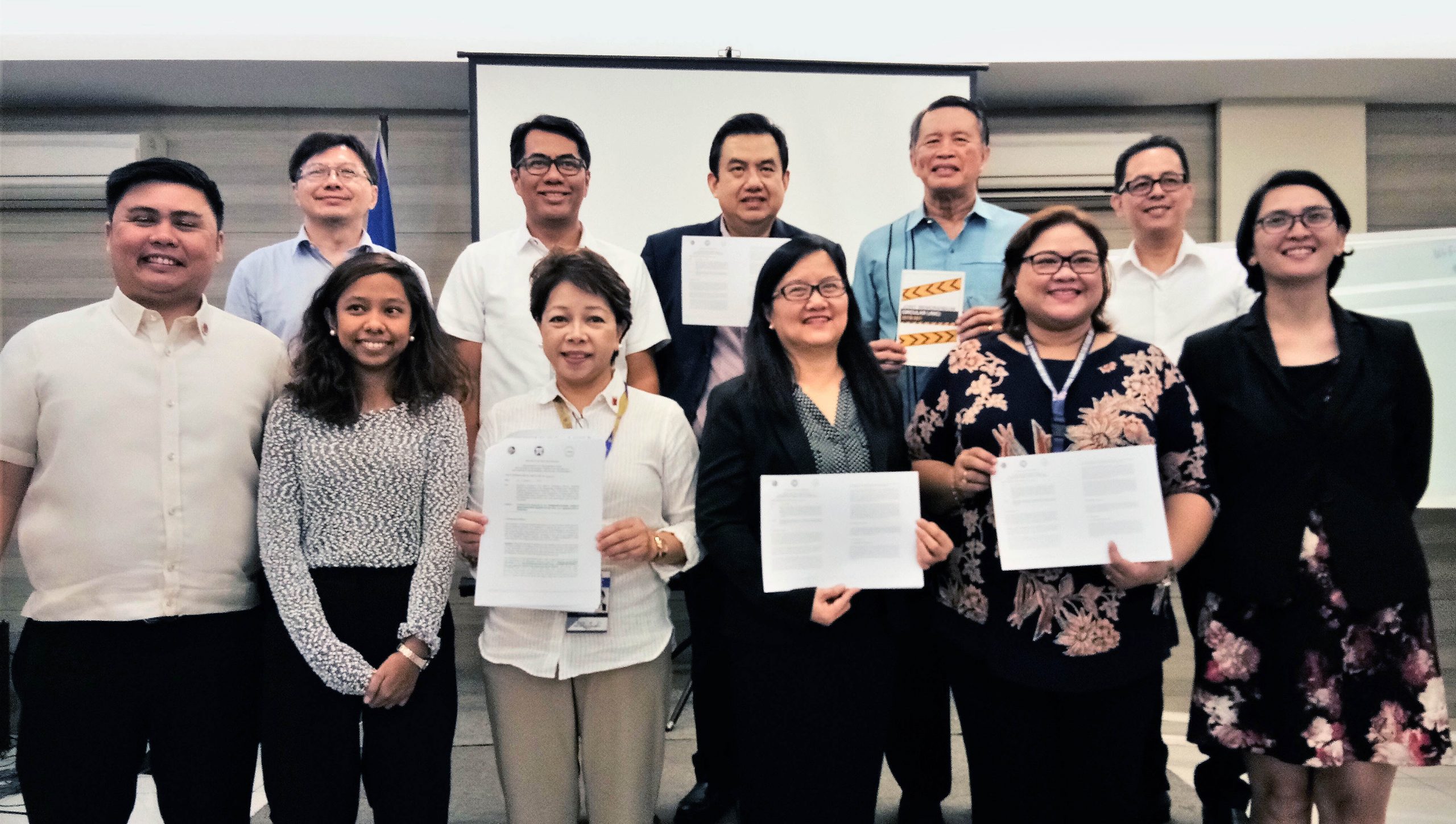

Lawmakers, law enforcers and road safety advocates convened Sept. 12 at the House of Representatives for a hearing on updates about road safety laws. Among those who attended were Land Transportation Office ASec. Edgar Galvante (in green), and Philippine National Police – Highway Patrol Group director Chief Supt. Roberto Fajardo (fifth from right) and spokesperson Supt. Oliver Tanseco (fourth from right).

In the House of Representatives committee hearing, riders group Motorcycle Rights Organization said they received reports of at least 14 areas allegedly implementing a no-helmet policy, meant to curb cases involving criminals riding in tandem.

Jobert Bolanos, chair of the Motorcycle Rights Organization, said these were:

- San Vicente City, Sto. Tomas, Batangas

- Brgy. 181, Pangarap Village, Caloocan City

- Silang, Cavite

- Cotabato City

- Brgy. Bagtas, Tanza, Cavite

- San Antonio, San Mateo, Isabela

- Villafuerte, San Mateo, Isabela

- Brgy. Chrysanthemum, San Pedro, Laguna

- Brgy. Malitlit, Sta. Rosa, Laguna

- San Fernando, Pampanga

- Labrador, Pangasinan

- Morong, Rizal

- Bagong Silang, Quezon City

- Brgy. Tatalon, Quezon City

At least two bills have also been filed at the House – HB 126 by Zamboanga City 1st District Rep. Celso Lobregat and HB 6542 by BUHAY Party-list Rep. Mariano Michael Velarde Jr – seeking to suspend RA 10054 to “deter the spate of crimes and killings by people riding in motorcycles.”

The Philippine National Police-Highway Patrol Group (PNP-HPG), believes the wearing of helmets should remain a must, and that motorcycle-related criminality could be addressed without sacrificing road safety.

“PNP-HPG fully supports the helmet law because it is for the safety of motorcycle riders,” said Chief Supt. Roberto Fajardo.

“But it should only be the helmet. Tanggalin na yung cover sa mukha, face mask, balaclava, the tint on the visor (Remove the face covers, face masks, ski masks, the tint on the visor),” Fajardo added.

Too many motorists, too few (deputized) enforcers

|

Laws |

Issue |

|

Motorcycle Helmet Act |

Too many motorists, too little enforcers |

|

Anti-Drunk and Drugged Driving Act |

Law enforcement personnel present in the House committee hearing reported they also find difficulties in implementing road safety laws with the number of enforcers disproportionate to motorists on the road.

According to the LTO, there are currently 6.1 million registered motorcycles in the country; 4.7 million are motorcycles without sidecar and about 1.4 million with.

There are only about 1,500 PNP-HPG personnel, said Fajardo.

The Anti-Drunk and Drugged Driving Law, in particular, requires that the LTO deputize first traffic enforcers from the PNP and Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA) before they are allowed to carry out the said law.

As of January 2018, only 300 PNP and MMDA personnel have successfully completed deputation seminars by the LTO.

PNP-HPG spokesperson Supt. Oliver Tanseco said seminars for the second and third batches of personnel to undergo deputation are ongoing.

Inter-agency conflicts cause accreditation delays

|

Law |

Issue |

|

Road Speed Limiter Act |

Speed limiters and testing facilities remain unaccredited |

Speeding just might also have been a factor contributing to the death of parking attendant Calacat, based on the observation made by a bar owner he had worked with for 11 years, who refused to be named.

“Nobody drives in Tomas Morato (at) more than 60 kilometers per hour,” said the bar owner. “But if you ask me, ganung impact? Ang takbo nun, as a driver, siguro pumapalo nang120 to 140 (That, in my estimation as a driver, could have been hitting 120 to 140 kph).”

The stretch of road between Sct. Fernandez street and Sct. Fuentebella, where Isabela province board member Ed Siquian Go sideswiped – and left dead – the area’s parking attendant, Celso Calacat.

Go’s car, currently impounded at Quezon City Police District Station 10 in Kamuning, now features a gaping hole on its front-right side.

If the bar owner’s hunch is correct, Go would have been running four to six times faster than the speed limits set by the Department of Transportation (DOTr) for passenger vehicles just this January, 30 kph for city roads and 20 kph for barangay roads.

Republic Act 10916 or the Road Speed Limiter Act of 2016 itself, despite having lapsed into law more than two years ago, remains to be implemented with speed limiter devices, installers and testing facilities still pending accreditation.

Intended to safeguard the public from speed-related road crashes, the law requires public utility vehicles, shuttle services, closed vans, cargo trucks and tanker trucks to have a standard speed limiter installed before they get registered under the LTO.

Various bureaus under the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) have yet to accredit the speed limiters, their installers and testing facilities after it found issues with the guidelines and implementing rules and regulations (IRR) of the law from the DOTr.

“When the DTI received the IRR for comments, (it has already been) signed and approved (by the) DOTr,” said Marimel Porciuncula, assistant director at the DTI Bureau of Product Standards (BPS).

“We should have been given more time to comment and review their draft,” she added.

Porciuncula said the current Philippine national standard, which would be the set specifications for speed limiters that may be installed in covered vehicles, needs to be declared as a technical regulation first under the DTI’s Consumer Protection Group.

Only after then would speed limiter devices and installers be tested by the BPS, while the speed limiter testing centers would have to go through the DTI-Philippine Accreditation Bureau.

“We understand that there are a lot of complications with regards to the implementation, but we just want to reiterate that the implementation of the law is long overdue,” said Global Road Safety Program project head Jason Salvador of the Ateneo School of Government.

“This is a disaster waiting to happen,” he added.

Yet advocates say road crashes, unlike natural disasters, could be prevented precisely through the implementation of safety laws, before they cause more deaths like Calacat’s, bereaving many families and friends.

“It’s different na wala siya (that he’s gone),” Calacat’s bar owner friend said.

Every night na darating ako dito (when I could arrive), he would always greet me with a smile,” the owner said, adding “we lost a family member.”

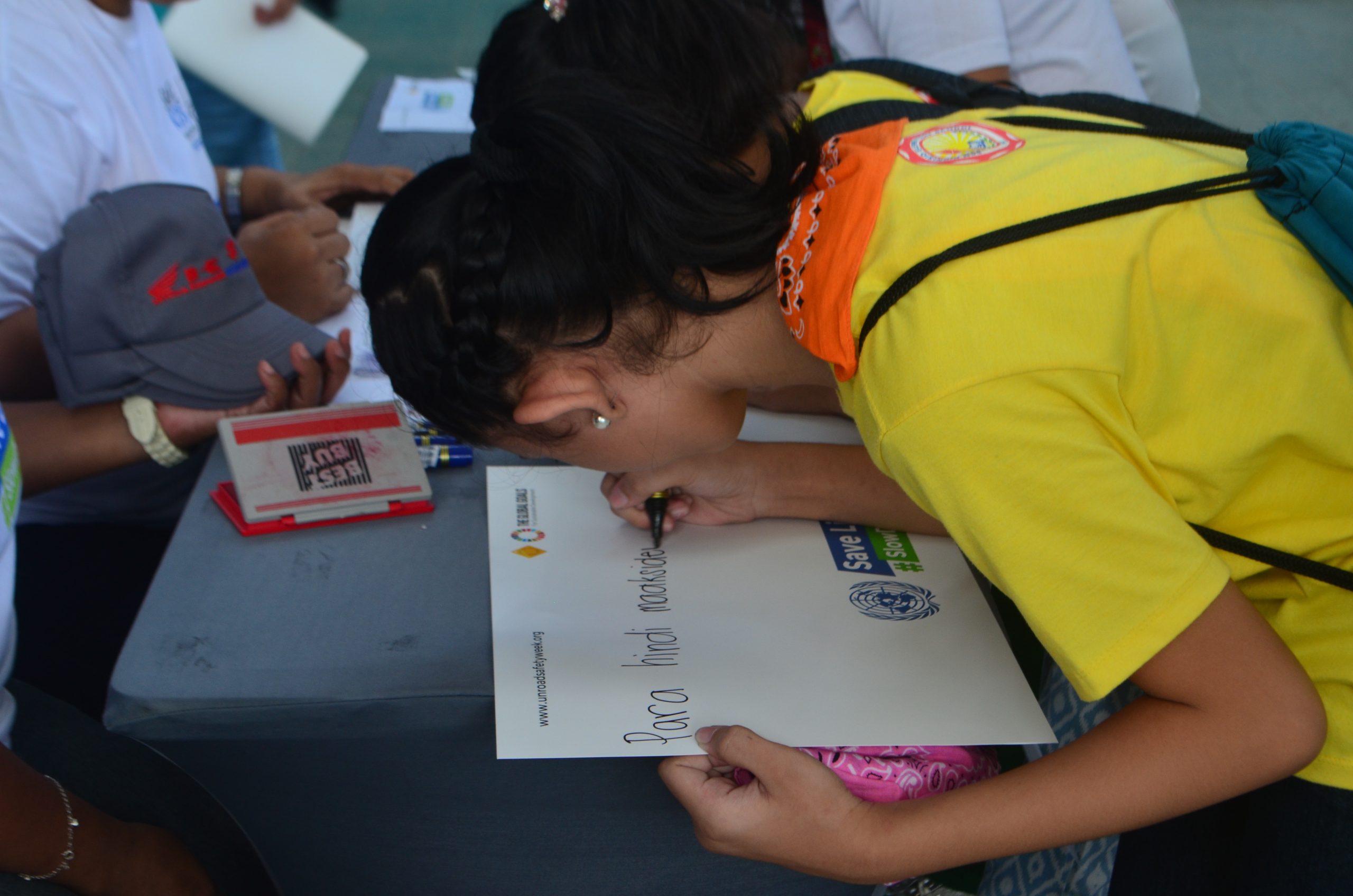

This story is produced under the Bloomberg Initiative Global Road Safety Media Fellowship implemented by the World Health Organization, Department of Transportation and VERA Files.