Every day, hundreds, maybe thousands, of workers from different socioeconomic backgrounds take their bicycles to work, school and other places of business.

One of them is Jong Tordesillas, who, at around 5:30 in the morning, is already suiting up in his cycling attire and getting ready to pedal. He lives in Manggahan, Pasig and rides his bicycle through C5 road up to McKinley Hill in Taguig, where he works as a project manager for a BPO company.

Never mind the pollution and occasional brushes with speeding vehicles, it only takes him 45 minutes by bike what would normally take him an hour-and-a-half car drive. “I also save money on parking fees and gas,” he says.

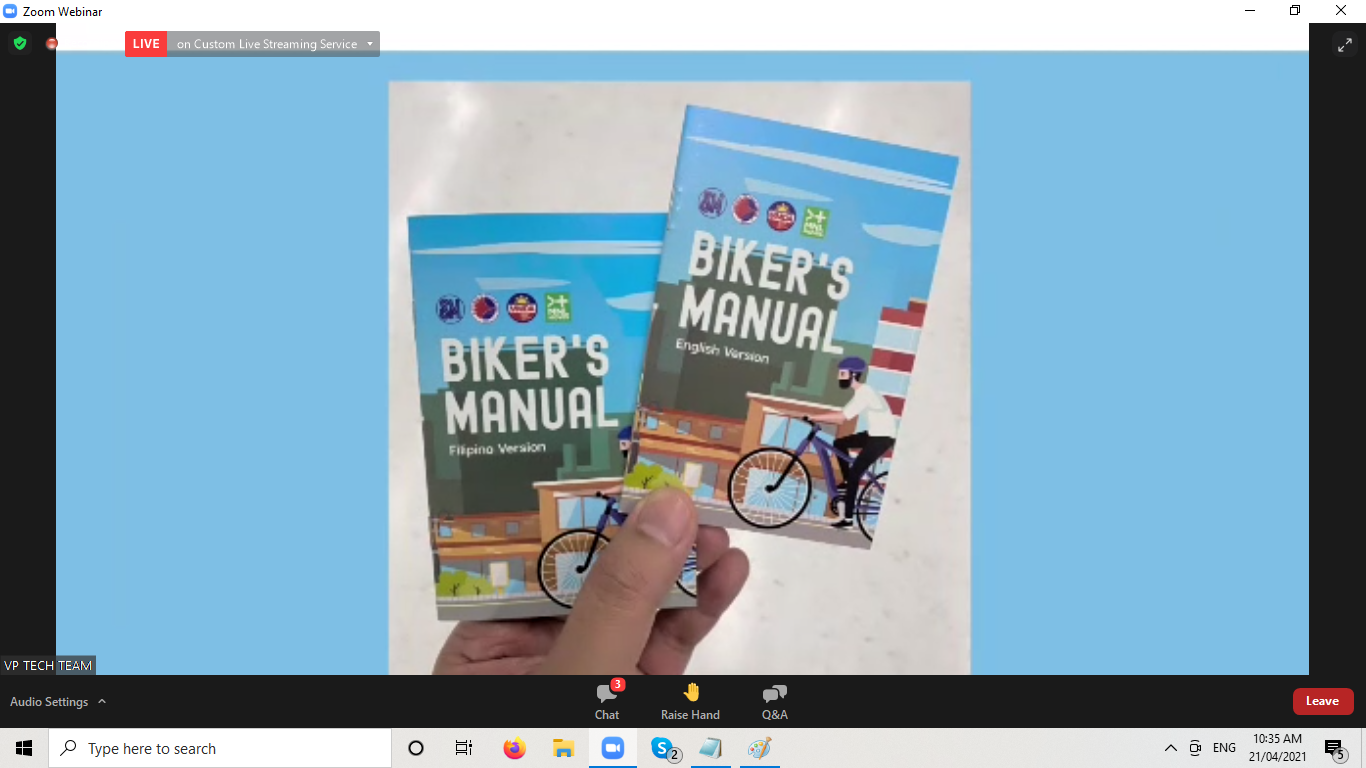

In a city like Metro Manila where there is an inefficient mass transportation system and hour-long gridlocks in major roads are daily occurrences, commuting to work by cycling is becoming a popular option. However, most roads currently do not have bikeways for cyclists, leading to lives lost or interrupted due to road crashes.

In 2015 alone, at least 26 bike riders were killed in Metro Manila because of road crashes, according to the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority. At least 962 people were also injured in bike-related mishaps.

One of them was Lorelie Melevo who died on the spot when she was hit by a dump truck after dropping off her five-year old son at school. She was using one of Marikina City’s bike lanes in a busy intersection along Mayor Gil Fernando Avenue when the truck ran her over.

Ironically, Marikina City is considered a model for integrating bike lanes in existing roads. In 2000, the city opened 100 kilometers of bike lanes. The network of lanes was designed to encourage citizens to use bikes as an alternative mode of transport and benefit those in the lower income segments by encouraging them to use their bicycles for commuting short distances.

Philippines not bicycle-friendly

For Tordesillas, biking to work is an option as he is also a car owner. He says he prefers to take his bike as it is less costly and saves him the headache of traffic jams. His company has also provided his fellow riders a bike rack and shower facilities.

Sometimes, he says, even construction workers and laborers from nearby sites park their bicycles in the company parking lot.

“Some of the bikes you see these men [construction workers and laborers] carry are old, they look like they’re bikes for children. Maybe it’s all they can afford. It’s a necessity for them,” he says.

Yet, despite the popularity of biking among laborers and other minimum wage earners, not enough infrastructures have been installed in the country to ensure their safety.

Julia Nebrija, an urban planner and MMDA’s assistant general manager, acknowledges that the Philippines “not bicycle-friendly” as it currently stands. There has been very little infrastructure investment on facilities for cyclists, she says. But she adds that more progressive thinking is factoring into plans and future projects.

In its 2017 Infrastructure Program, the Department of Public Works and Highways proposed a P458-billion budget to undertake the country’s most ambitious infrastructure program. This includes building new highways, expressways and flyovers in Metro Manila such as the NAIA Expressway and the NLEX-SLEX road connector.

The DPWH has earmarked more than P247 billion for the construction of new roads that would improve vehicle usage capacity, taking up 57 percent of the department’s annual budget.

Nebrija notes that plans for C6, a 34-kilometer toll road from Taguig to the Batasan Complex in Quezon City, will incorporate a bike way. The Department of Transportation and the MMDA, she adds, have more plans to improve infrastructure for pedestrians and bikers.

Rise in motorized vehicles

It calls for a change in thinking, Nebrija says. In the current fight for space in Metro Manila, private vehicle use is being prioritized given increasing car ownership in the country. This, despite studies showing that more infrastructure for cars only begets more cars, and more traffic.

This growth in car ownership in recent years coincided with the boom in Metro Manila’s population as well as the considerable economic growth the country experienced between 2010 and 2014.

In 2015, the automotive industry sold 60,000 more units, a 22-percent increase over 2014, according to a report by the Chamber of Automobile Manufacturers of the Philippines Incorporated. The report also projects that the Philippines will become a major car market by 2020.

Motorcycle ownership has also been on the rise. According to the 2016 Land Transportation Office annual report, 1.4 million new motorcycles were registered in the country last year, an increase from the previous year’s 1.1 million.

The Philippines, currently the sixth largest market for motorbikes globally, is set to become Southeast Asia’s third biggest market for motorcycles, according to the Motorcycle Development Program Participants Association.

Motorcycles are seen as an inexpensive alternative to cars and have the ability to slide through narrow spaces during high traffic.

“With inefficient public transport, we will lose them [commuters] to motorcycles,” Dr. Ricardo Sigua, a professor at the University of the Philippines College of Engineering and a fellow at the National Center for Transportation Studies, says.

But with the dominance of four-wheelers in the country, having more motorcycles on the road could also mean more road crashes, he says.

Meanwhile, data on the number of bike riders in the country are difficult to obtain, as the government does not require registration of non-motorized vehicles except for electronic bicycles, which are required to be registered with the LTO.

Fight for space

The competition for space among public and private vehicles as well as cyclists and pedestrians is an issue, Sigua says. “Improvement of sidewalks to share with pedestrians and cyclists could be a solution,” he says.

However, there is a danger in sharing the road between motorized vehicles and non-motorized ones such as bicycles. The likelihood of a vehicle crushing a cyclist during a road altercation is very high. And, due to diminishing spaces on the road, the risk is compounded by a general attitude among car users that cyclists are annoyances on the road.

Sigua believes it would be difficult to install a metro-wide system of cyclists within the current infrastructure.

Proper implementation of infrastructure from the start is key, he says. Bikeways should not be mere add-ons but must already be incorporated into the plan, he adds.

While there had been numerous bills introduced in Congress in the past, proposing the construction of cycling paths and sidewalks for cyclists and pedestrians alike, these did not gain much traction.

Erwin Paala, leader of the We Want Bike Lanes In RP movement, believes the battle should not be between car users and cyclists, as both have a right to use taxpayer-funded roads. Paala’s group believes that installing bikeways and creating spaces designated solely for cyclists and pedestrians could not only save lives but also return economic benefits to those who bike daily to work.

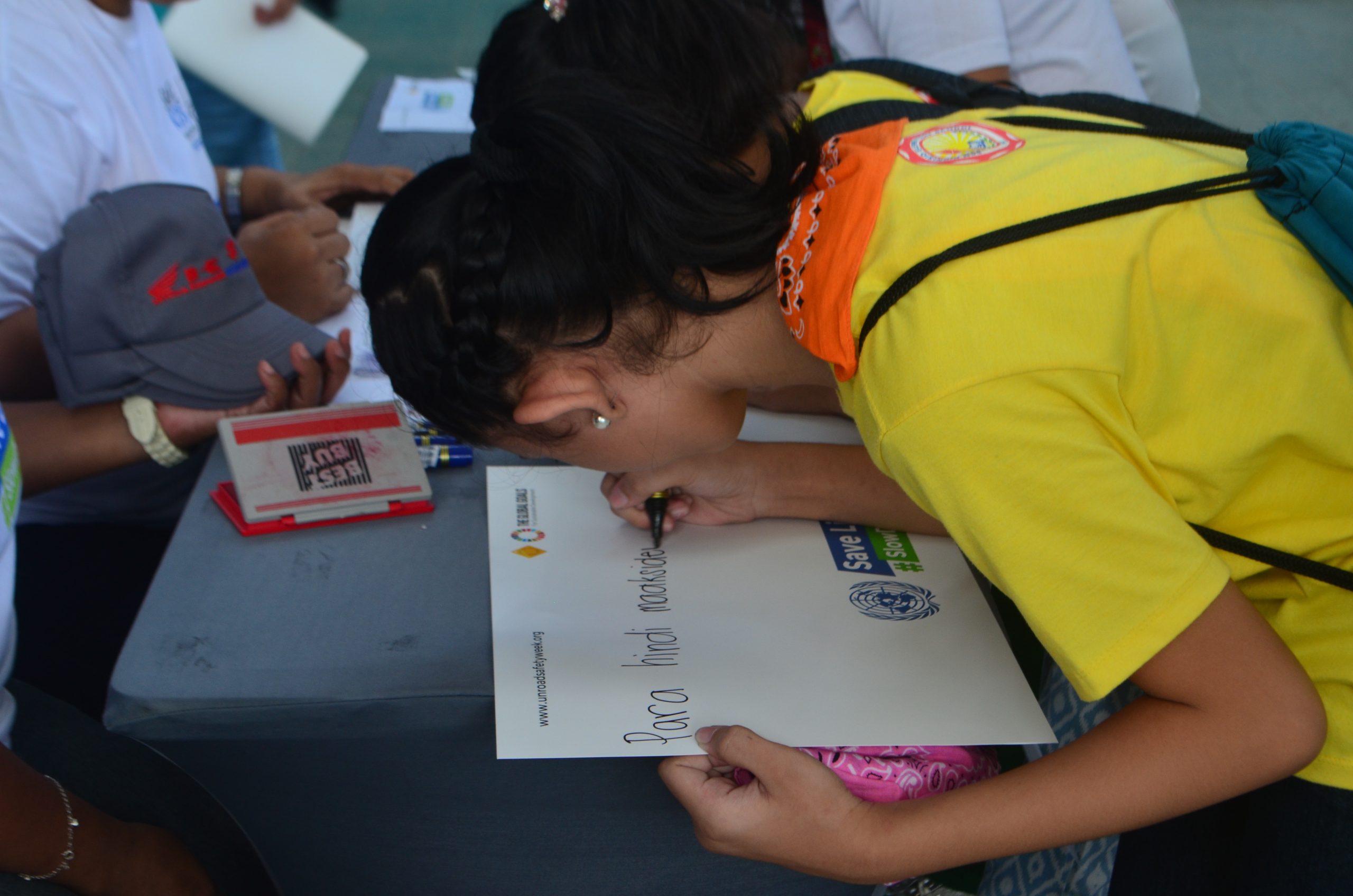

Paala says the imperative to protect the safety of cyclists and pedestrians must be elevated to the level of valuing human life.

“In the last 10 years, there have been 196 deaths caused by road crashes. Some of these people are breadwinners. And those who survive the crashes suffer injuries that prevent them from working. These are workers who were once part of a vibrant workforce,” he says.

Not only does the money saved from paying fares augment the family budget, improving infrastructure for cycling is also an economic investment for the entire country.

This story, first published at Interaksyon, was produced under the Bloomberg Initiative Global Road Safety Media Fellowship implemented by the World Health Organization, Department of Transportation and VERA Files.