Four years after one of the country’s most deadly road tragedies, the government and civil society groups have crafted a new policy that would help prevent its repeat, targeting what they say is the most significant contributor to road fatalities — speeding.

Signed Jan. 17, the joint memorandum circular (JMC) 2018-001 “strengthens and implements” Republic Act 4136 or the Land Transportation and Traffic Code, which mandates national and local government units (LGUs) to classify their roads and set corresponding speed limits, according to the ImagineLaw, a nonprofit organization that pushed for and helped craft the JMC.

With the circular, LGUs will be able to lower speed limits when needed, subject to the approval of the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) and Department of Transportation (DOTr).

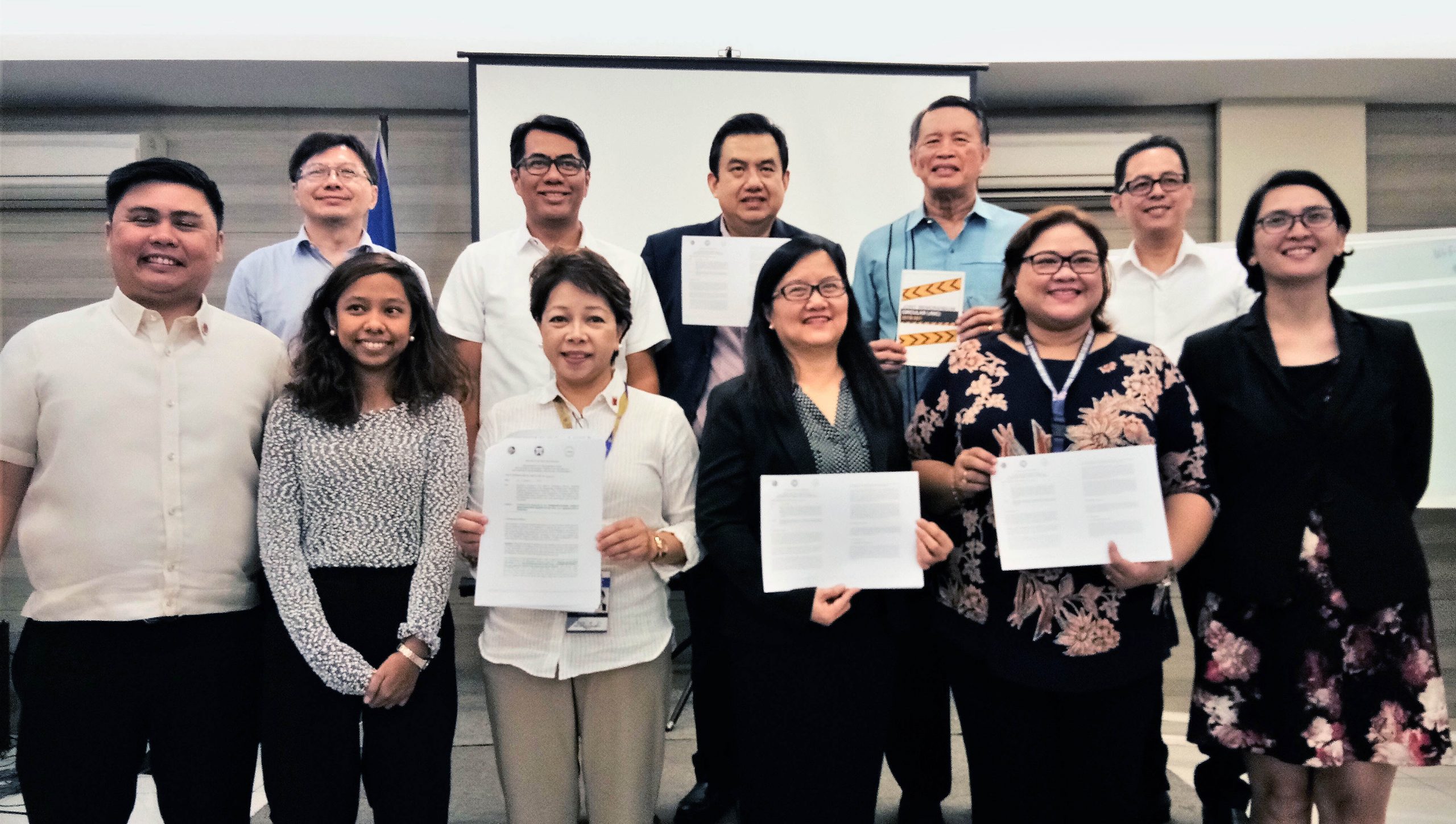

Signed by these agencies along with the Department of Interior and Local Government, the circular was launched in Quezon City Feb. 7, exactly four years after a bus in Bontoc, Mountain Province fell off a ravine and killed 14, including artist Tado Jimenez, and injured 32. Initial probe showed loose brakes caused the crash, but speeding was the real culprit, explained lawyer Sophia San Luis, executive trustee of ImagineLaw.

“Many city and municipal governments in the Philippines have not yet classified roads within their jurisdiction or set local speed limits pursuant to their mandate,” she said.

Of the 229 cities and towns ImagineLaw identified in its 2016 study, only 56 had speed limit ordinances.

“None of those 56 actually classified their roads under RA 4136. None,” San Luis said. “That is why there is virtually no speed limit enforcement.”

Lawyer Sophia San Luis of nonprofit ImagineLaw explains the salient points of the new circular.

The World Health Organization (WHO) identified speeding as one of the key behavioral risk factors in road crashes, with others being drink driving; distracted driving; and non-use of motorcycle helmets, seatbelts, and child restraints.

“Speeding is the most important contributor to road fatalities,” the circular stated.

It cited Philippine National Police data on the rising trend in road crashes, from 12,875 in 2013 to 32,269 in 2016.

Philippine Statistics Authority data also showed an increase in the number of road fatalities nationwide, from 6,869 in 2006 to 10,012 in 2015.

“The government must really ramp up its effort in order to reverse this trend,” San Luis said.

The WHO identified speed-limit setting as one of the most “cost-effective” way to curb fatal road crashes, quoting studies that prove increasing vehicle speed resulted in more crashes, while slowing down meant less crashes.

Recognizing that speed “is at the core of the road injury problem,” the JMC harmonized existing road classifications under the DPWH manual with the speed limits set under the law.

On a national road, for instance, the DPWH manual mandates a speed limit of 80 kilometers per hour on a flat topography. But the maximum allowable speed gradually dips to 20 kilometers per hour if a vehicle passes what is classified as a “crowded street,” or those within the 500-meter radius of schools, churches or markets.

Under the new policy, LGUs with existing ordinances must submit these to regional Land Transportation Offices (LTO) for review.

It came with an 11-page template of a speed-limit ordinance, following problems in cities like Cebu and Iloilo.

According to ImagineLaw, Iloilo City could not implement an existing ordinance after it left out procurement of speed guns, used to measure a vehicle’s speed. However, it has since proposed installing an “integrated traffic system” to enforce the law and included the fund in its 2017 budget proposal.

Cebu City, which had approved purchasing speed guns in 2011 for its South Coastal Road but has since failed to buy one, has in 2016 considered partnering with a private firm to install two automated speed cameras, the study added.

Transportation Undersecretary Thomas Orbos said the department eyes placing speed guns on Metro Manila streets, adding that the LTO is set to request funds from the Road Board to procure some 200 items.

Stressing the importance of speed-limit setting, San Luis cited Davao City, which in 2013 placed speed guns and placed signs on streets with the highest road fatalities, while heavily publicizing the policy.

A month after its enforcement, the city reported a 10-percent decrease in road crashes. In 2014, fatal road crashes went down by 60 percent, while minor ones dipped by 20 percent.

“Their enforcement is so strict,” San Luis said. “Even Mayor Sara Duterte and Vice Mayor Paolo Duterte had been apprehended for speeding (and) issued citation tickets which they paid for.”

Yet, while Orbos is certain that the circular will help curb road crashes, he said unless the policies are instilled in motorists themselves, “road safety will just be something that will not be implemented fully.”

“Our government programs cannot stand on its own,” he added. “We need everyone’s participation and conscious effort to follow road safety rules.”