Manufacturing fake news is hardly a noble job, so why do people do it?

A new study found that money is not the only motivation of these so-called “disinformation architects.”

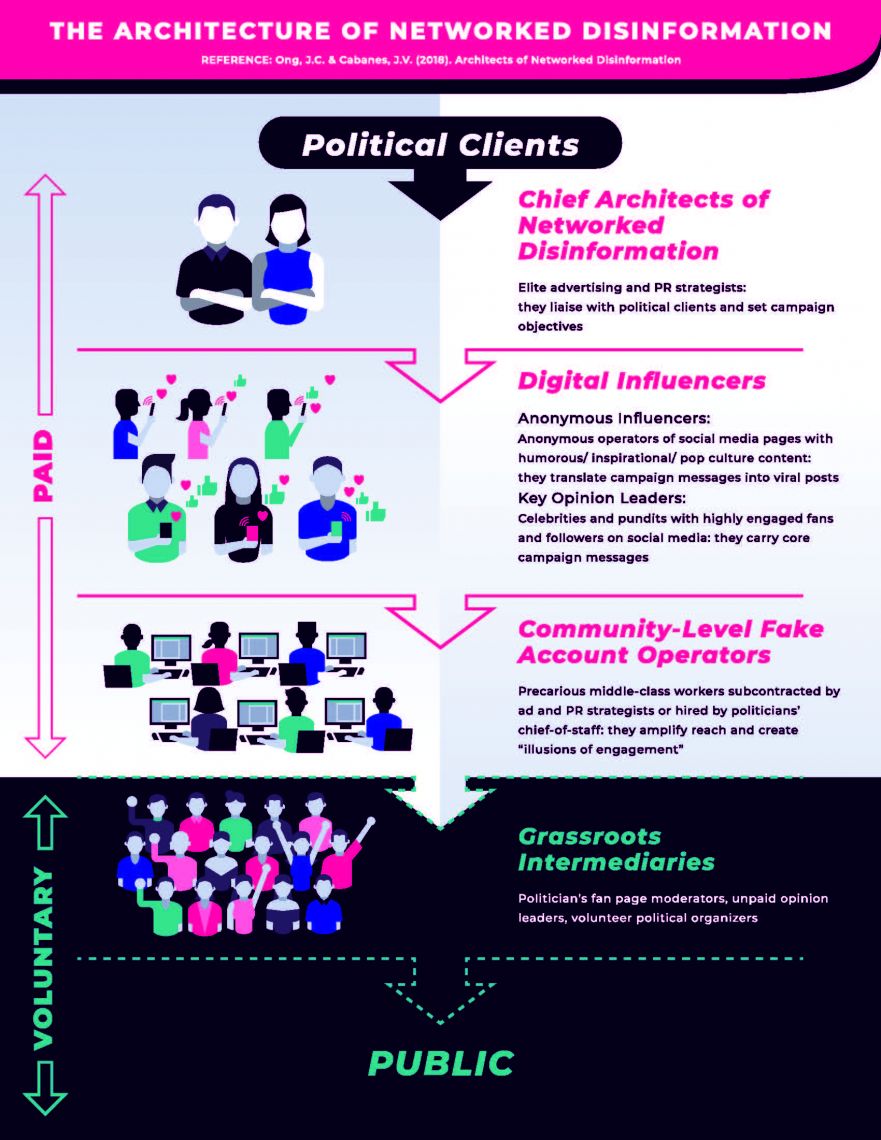

Advertising and public relations executives, social media influencers and fake account operators that make up the network of “disinformation architects” are all driven by financial, political, social and psychological motivations in several ways, says the study by media scholars Jonathan Ong and Jason Cabañes.

Some disinformation architects even liken their work to fictionalization, with one of them telling the authors, “This is straight out of ‘Game of Thrones.’”

Ong, an associate professor of the University of Massachusetts, and Cabañes, a lecturer at the University of Leeds, are releasing their report, “Architects of Networked Disinformation: Behind the Scenes of Troll Accounts and Fake News Production in the Philippines,” on Feb. 12 at the Democracy and Disinformation conference in Makati City.

The researchers, who interviewed disinformation architects and observed the fake accounts they operate, found that most workers are politically aligned with their clients as well as lured by money.

Some disinformation architects, however, justify their work, saying the production of fake news is the same as handling corporate brands. Others view their work as a sideline “and expressed a wish to be judged based on their primary jobs and/or future aspirations,” the study said.

Infographic lifted from the study “Architects of Networked Disinformation: Behind the Scenes of Troll Accounts and Fake News Production in the Philippines.”

Some became disinformation architects after “being disillusioned in the creative industries from witnessing first-hand systematic corruption” or unfair work arrangements, according to the study.

In the course of having to revise history, silence political opponents and hijack news media attention, “workers develop implicit rules to establish a moral order and distance themselves from the stigma around trolling,” the study said.

They do so by “dismiss(ing) their own personal responsibility to democratic processes and political exchange,” it added.

“Doing edgy, experimental work” is also said to bring them fulfillment, the study said.

President Rodrigo Duterte’s victory in the 2016 election has been partly credited to his social media strategy.

In 2017, United States nonprofit Freedom House noted how “keyboard trolls” operate to attack the president’s detractors, both during and after the election. The Palace has denied the claim.

But different political parties at both national and local levels, not only Duterte and his PDP-Laban party, make use use of “click armies,” the study said.

The study said chief strategists (advertising and PR executives) set campaign objectives based on input from their political clients, then delegate political marketing responsibility to a team of digital influencers and fake account operators. The operators, in turn, infiltrate online communities, artificially trend hashtags and spread disinformation.

Interestingly, the study said citizens easily consume disinformation because they are used to deception provided by “legitimate sources” corporate brands, celebrities, journalists and the media.”

“This longstanding acceptance paved the way for political disinformation to thrive unregulated in a digital underground that only very subtly hides from plain sight,” it noted.

Ong and Cabañes stressed there is “no one-size-fits-all solution” to networked disinformation.

Efforts exposing fake news sites and accounts“ do not address the institutions and systems that professionalize and incentivize disinformation production,” they said.

Disinformation architects also exploit the gaps in self-regulation among advertising and PR industries, coupled with campaign finance legislation, they added.

Saying the manufacture of fake news in the Philippines may have implications on countries such as the United States, the researchers urged global actors to look into the fake news production it calls “a stockpile of digital weapons.”