In the fight against disinformation, there is a need to go beyond personality-based name and shame campaigns, and instead analyze the complicity and collusion of professional creative workers in the fake news industry, the latest study by the authors of the 2018 breakthrough report “Architects of Networked Disinformation” in the 2016 elections, said.

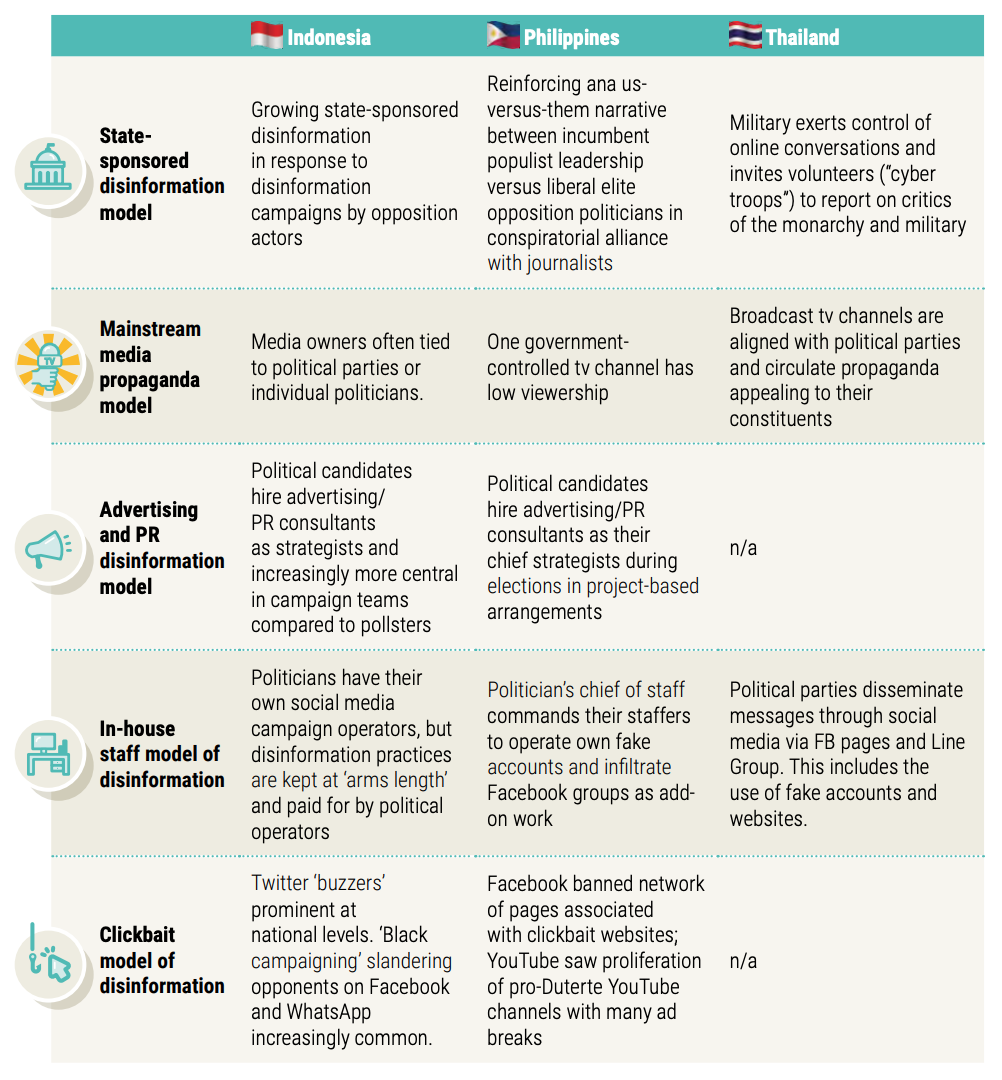

In their latest study, “When Disinformation Studies Meets Production Studies: Social Identities and Moral Justifications in the Political Trolling Industry,” Jonathan Corpus Ong from the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and Jason Vincent Cabañes from the De La Salle University, looked beyond the usual discourse on the weaponization of disinformation in forwarding political agenda, which usually cages disinformation agents as the bad guys and analyzed the systems and culture rooted in public relations, advertising, and marketing practices which allow and normalize this organized production of digital disinformation.

” A production studies approach thus sheds light into how digital disinformation is not an all-new Duterte novelty; it is in fact the culmination of the most unscrupulous trends in the country’s media and political culture. Many of the techniques of disinformation were first tried and tested in marketing shampoos and soft drinks before extending them to marketing politicians and their narratives. The difference is that seeded hashtags that aim to drown out dissent pose greater dangers to political futures,” Ong and Cabanes said.

Trade-offs

The authors acknowledged the conceptual as well as political trade-offs in taking a production studies approach to digital disinformation.

The first trade-off, the authors said, is that instead of naming and shaming high-profile personalities, it maps out the broader system and incentive structures to fake news production.

” For us, this offers a corrective to current initiatives dedicated to fact-checking fake news, “the duo said.

The second trade-off is that instead of mobilizing a heroes-and-villains frame when talking about fake news, we reflect on everyone’s “complicity and collusion” in its practice, they added.

The third trade-off is that instead of focusing policy lobbying efforts at global-level content regulation by the tech platforms, we highlight local-level process regulation aiming for transparency in the context of political campaigns and influencer marketing, they further said.

Justifying disinformation work

The study said in the researchers interview with 20 “disinformation producers” composed of PR and advertising experts, “anonymous digital influencers,” and “community level fake account operators,” they were able to determine two key features of networked disinformation.

First is that advertising and PR principles play a big role in the development of political disinformation campaigns. PR and marketing experts who are placed at the top of the hierarchy and serve as the “chief architects” of disinformation campaigns cleverly utilize their knowledge on public relations and advertising they were able to acquire from their jobs in the corporate.

Second, digital campaigns of disinformation are usually project-based in nature, where individuals only treat taking part in the production as a “sideline work.” Some of the participants of the research were people who keep their day jobs as advertisers and online marketers.

These two features pose significant implications on the production of disinformation. Because these agents are all familiar with the principles of PR, the competition between each of them in satisfying their clients is fierce as they all try to craft “attention-hacking” content with “greatest potential.”

Disinformation producers also have the tendency of justify to others and to themselves the nature of what they are doing, in result dangerously downplaying the impact of their job.

One of the interviewees, a certain ‘Dom’ who is said to have a “long record of handling high-profile candidates including presidential aspirants,” showed how much they enjoy the “thrill and adrenaline rush” they get from political marketing.

“Maybe if I had this power 10 years ago, I would have abused it and I could toy with you guys. But now I’m in my 40s, it’s a good thing I have a little maturity on how to use it. But what I’m really saying is we can f*ck your digital life without you even knowing about it,” Dom said in an interview.

Meanwhile, other disinformation agents justify their participation in the disinformation production by soft-pedaling their involvement in the process.

“Being a character or a ‘pseudo’ is only very fleeting because you are not the person. You just assume that personality. You trend for a while and then move on,” Georgina, one of the anonymous influencers who participated in the study, justified their shallow attachment on their disinformation-production work by waving the “fleeting” nature of the job.

But what was undeniably evident in the results of the study, is the fact that financial motivations of individuals remain as great drivers of the disinformation industry. People who are in the lower ranks of the hierarchy, such as the anonymous influencers and fake account operators, cited their less stable day jobs as one of the main reasons why they found themselves taking part in the disinformation work.

By looking not on the villainous characteristics of the players in the digital disinformation industry but on the principles they operate in and motivations which drive them into this job, the study was able to contribute to the bigger picture of the disinformation ecosystem which the political sphere is capitalizing on today, the authors said.

“We see our work as also speaking ‘’truth to power’ to those in high positions of economic power in the creative industries who consider themselves ‘kingmakers’ in the political realm,” Ong and Cabanes said, as they call for regulations which would specially target transparency and accountability from top-level advertising and PR strategists, and their employers—the people directly benefiting from the fruits of political digital disinformation.