The outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) this year came not only as a challenge to medical institutions and health care systems, but also as a socioeconomic burden gravely affecting all sectors of society, especially the poorest.

Unemployment rate hit a peak in April, recording 17.7 percent or 7.3 million jobless Filipinos. By October, it went down to 8.7 percent—equivalent to 3.8 million unemployed individuals—which was still 1.8 million more than the same period last year.

The Philippine Statistics Authority attributed April’s record unemployment to the “COVID-19 economic shutdown,” after community lockdowns were imposed across cities and municipalities in an attempt to contain the spread of the virus.

To help people who lost their jobs due to restrictive quarantine protocols, the government promised to provide 18 million low-income households with monthly cash assistance worth P5,000 to P8,000 for two months, under the Bayanihan To Heal As One Act. The distribution of the subsidy started in April and is ongoing in some places.

Scammers saw an opportunity to take advantage of this government response to the pandemic.

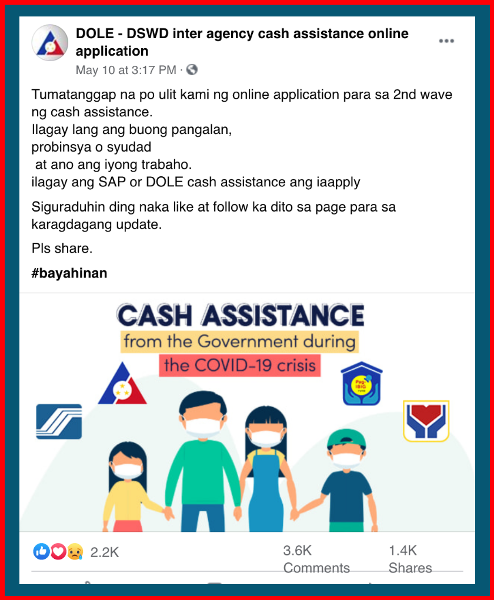

Last May, VERA Files Fact Check (VFFC) flagged two fake Facebook (FB) pages: one pretending to be a Social Amelioration Program (SAP) updates page, the other posing as the official “interagency” page of the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) and Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD).

While the first only claimed that a “tentative schedule” for the second wave of cash aid distribution has been set, inviting FB users to “like” and share their page for updates, the second instructed netizens to provide their full name, address, and profession in the comments section of its post, pretending to be an official application portal for the cash subsidy.

The second page easily convinced Filipino netizens to give their personal data, receiving over 3,600 comments in just two days after its spurious post was published.

Many netizens who took the bait said they were in a “no work, no pay” employment status due to the pandemic. One of them said she is a lady guard in a Quezon City mall who lost her source of income because of the mall’s closure. Another described herself as a solo parent with a child suffering from a heart condition, while a third one said he is an overseas Filipino worker “stranded” for five months in an accommodation in Pasay City and has not received any form of assistance.

While seemingly harmless, posts like these that phish personal information can actually be dangerous.

Jonathan Ragsag, division chief of the National Privacy Commission (NPC)’s Data Security and Technology Standards Division, said people behind the fake pages could use the personal data they illegally collect “for another purpose which is unauthorized under the law,” such as committing different crimes using stolen identities.

Scams can lead to identity theft

Computer-related identity theft, as defined under Republic Act 10175 or the Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012, is the “intentional acquisition, use, misuse, transfer, possession, alteration or deletion” of a person’s identifying information.

Data from the Philippine National Police – Anti-Cybercrime Group (PNP-ACG) obtained by VERA Files revealed that computer-related identity theft ranks third in terms of the number of cybercrime cases handled by the ACG from January to October this year.

The unauthorized acquisition or collection of personal data, the first step of committing the crime, is done in many ways—one of which is through online scams.

Typical online scams come in the form of fake giveaways and raffles done by accounts on social media, often pretending to be official accounts and pages of public figures to create an impression of legitimacy.

Since January, VFFC has flagged 12 fake online giveaways. Most of them were by FB pages and accounts posing as prominent personalities and businesses, such as Senator Manny Pacquiao, game show host Willie Revillame, and even the hardware and software company Hewlett Packard (HP).

Many times, these impostors require interested netizens to “like” their pages and affiliate accounts to generate following. This is an asset they could later on use to earn money, either by removing all their prior posts and replacing them with promotional content, or by selling the pages to new owners who would use them in other purposes.

This modus, however, has leveled-up. Other creators of fake pages are now asking for more than just “likes.” They are now collecting people’s personal data, similar to what the fake DSWD-DOLE page did.

Ragsag said a person who collects the data could use it to pretend to be another person and commit a crime.

“Magpapanggap na sila, magpagawa ng passport [using] identity nila, and then makalabas ng bansa, and then hindi natin alam ano ba sila. Sila ba ay potential terrorist (They would pretend to be another person, would get a fake passport using someone else’s identity, would be able to get out of the country, and then we will never know who they are. Are they potential terrorists)?” Ragsag said in a phone interview with VERA Files.

He also warned about stolen identities being used to apply for bank loans. He cited a case from 2016, where a public school teacher found himself deep in debt after his identity was wrongly used to secure loans from three banks.

The suspect got the victim’s personal information from his Professional Regulation Commission (PRC) identification card, which he posted on FB.

The netizens who fell for the fake DSWD-DOLE page’s post could easily find themselves in the same situation as the teacher, since fabricating a PRC ID only requires a person’s full name, photo, and a registration number.

Police Major Joseph Arvin Villaran, public information officer of the PNP-ACG, said there are many other possible crimes that could root from computer-related identity theft.

“‘Yung online libel tsaka online estafa, ang pinanggagalingan talaga niyan is ‘yung computer-related identity theft (Online libel and online estafa really start with computer-related identity theft),” he told VERA Files.

Villaran said identity theft could turn into online libel when a culprit hides his or her real identity by using a stolen one, and uses it to defame other people. It will become online estafa or swindling if the culprit uses the stolen identity to commit fraud on people, with the goal of acquiring money from them.

It could even go as far as extortion, which happens when the culprit uses the illegally collected information to force its original owners into paying a sum of money by blackmailing them, he added.

Computer-related identity theft is punishable under R.A. 10175 by six years and a day to 12 years of imprisonment, with a minimum fine of P200,000.

The Revised Penal Code sets a penalty of six months and a day to four years and two months of imprisonment or a fine of P200 to P6,000, or both, for libel, aside from a possible civil lawsuit. Swindlers, on the other hand, could be charged with two months and a day to 20 years of prison, depending on the amount of the defrauded money.

Another possibility of a crime Villaran mentioned is when the culprit hacks someone’s social media account using the data he or she stole, and then victimizes the account owner’s friends and followers.

“So parang talon-talon na (So, it’s like it’s jumping [from one crime to another]),” Villaran said.

Government, netizens’ measures against cybercriminals

Ragsag said that the NPC is very much aware of the “heightened risks” of online scams during the ongoing pandemic, as posers and fraudsters are “exploiting the public fear” to get people to fall into their traps.

In a public bulletin released on March 23, the Commission appealed to netizens to “be very careful online,” and reminded them to make “trusted government and other legitimate websites” their go-to sources of information, especially on COVID-19 related topics, in order to not fall victim to misinformation.

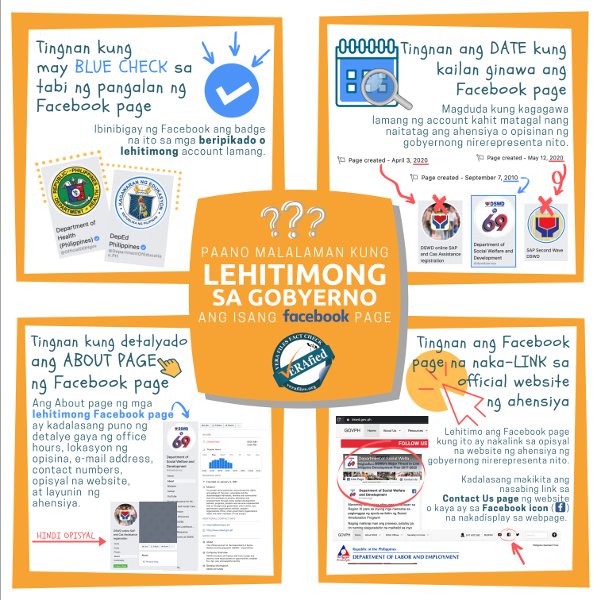

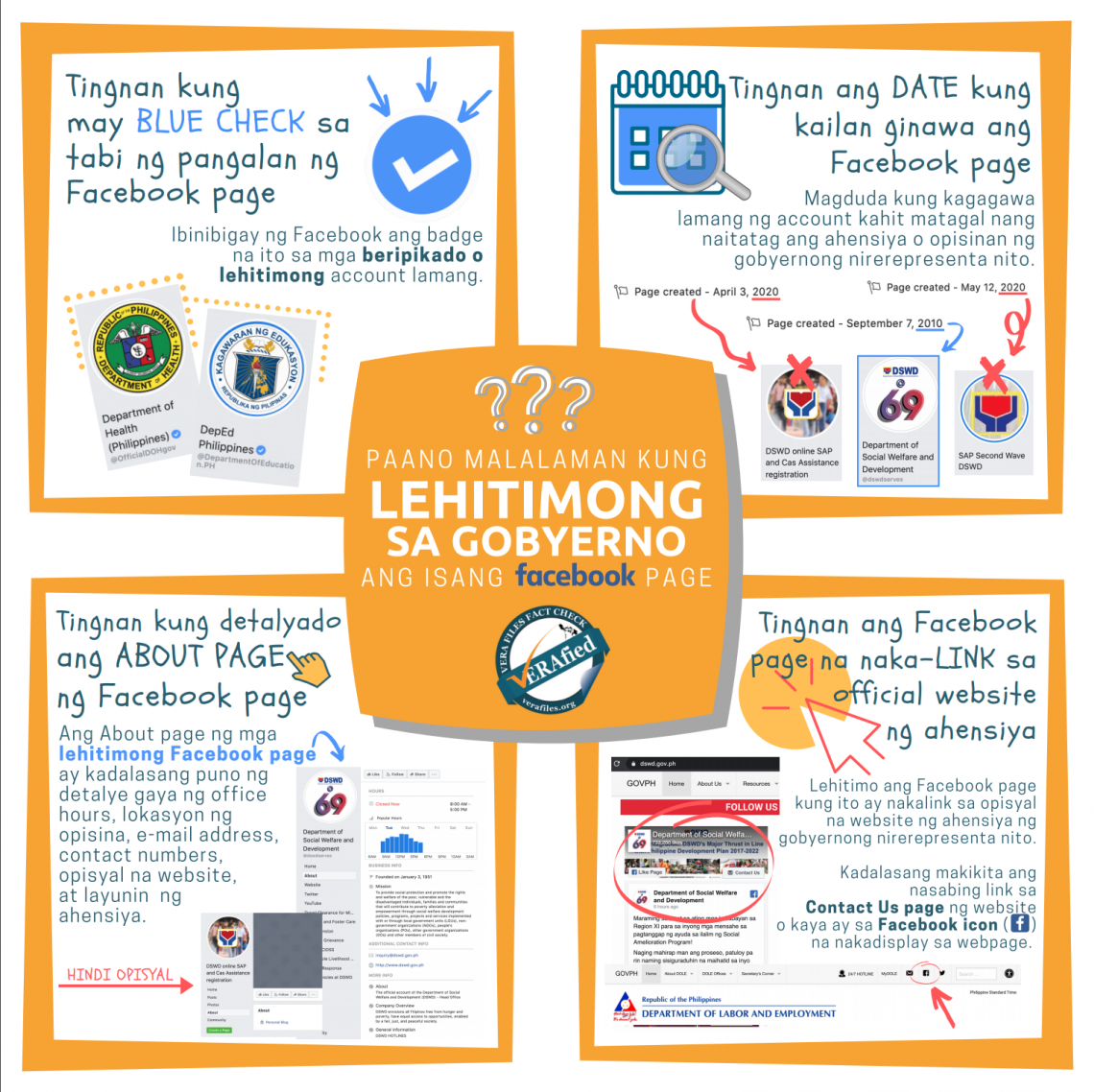

However, the number of engagements received by the impostor pages strongly suggests the inability of many Filipino social media users to differentiate legitimate pages and accounts from bogus ones.

Unfortunately, as far as Ragsag knows, there are no specific guidelines set for government offices when creating their official social media accounts. For example, not all official FB pages and Twitter accounts of these public institutions have “blue” checks. This could have been a helpful indicator for netizens in determining the verified—thus, official—government accounts.

In February 2018, the Department of Information and Communications Technology (DICT) announced that a draft “Administrative Order (AO) on Social Media Use of the Government” was already in its last round of public consultations, which included discussions on “dealing with trolls and fake pages.”

A Philippine News Agency article said the AO “seeks to provide [a] framework for government agencies to manage their social media accounts.” But President Rodrigo Duterte has yet to sign the order, and there has been no update about it since February 2018.

Ragsag said this lack of policy “could be a room for improvement” in the future. For now, he encourages each government agency to “look at their own security measures” and inform the public of their official pages and accounts—something that the NPC is already doing, according to Ragsag.

As for the tracing and arrest of individuals or groups behind the fake FB pages, he said apprehending them will need a “whole of government approach” that would involve the PNP, the National Bureau of Investigation, and the Department of Justice.

“‘Yung whole of government na approach na po ang ating kakailanganin. Pagdating sa pag-trace sa kanila, I would believe mas equipped itong mga law enforcement agencies natin para habulin po ito (We would need the whole of government approach for this. When it comes to tracing them, I believe these law enforcement agencies are more equipped to go after these people),” Ragsag said.

On NPC’s part, Ragsag said the Commission will act on any complaint filed by a netizen who may have been a victim of unauthorized processing of data.

Meanwhile, PNP-ACG’s Villaran advised netizens to be wary of “too good to be true” online giveaways and raffles with big cash prizes. According to him, “no one would just give away huge sums of money that easily.”

“Kung humihingi sila ng details sa’yo through online, tapos hindi mo kilala ang nasa other end, wag niyo na ituloy ang transaction ninyo. Peke ‘yan — hundred percent (If they ask for your details and tell you to send them online, and you do not know the identity of the person asking, don’t push through with the transaction. It’s fake — one hundred percent).”