By FERDIE C. MARCELO

WHEN Yolanda lashed Samar and Leyte in November 2013, feet tripped on feet to contain the damage. The statistics that surfaced five months after were terrifying: 6,300 dead, 4.1 million displaced, and 1.1 million houses damaged or destroyed.

To this day the effects are still being felt by the villagers, mostly in the form of shortages of basic necessities such as potable water, dwellings, and electricity.

In the municipality of Tolosa in Leyte, for example, which was hit in Yolanda’s second landfall, 90 percent of the coconut trees were felled, 80 percent of rice paddies were flooded, all banana trees wiped out, and nearly all of their livestock killed.

Even after the rehabilitation of the Leyte Water District, supply is still not reaching areas that are some distance from the main pipe running through the highway such as Barangays Burak, San Vicente, Capangihan, and Tanghas.

The residents get water from shallow wells that are contaminated with coliform, and most, especially the children, are afflicted with gastrointestinal diseases.

Hindsight, as usual, highlights mostly regrets than lessons that should be learned. If only the mangroves were still there to act as a natural buffer, the devastation would not have been so utter.

Efforts to rehabilitate the mangroves post-Yolanda are encountering issues too, especially among some scientists up in arms saying only mangrove species endemic to an area should be planted, otherwise it’s all a waste.

Defense against typhoons

The importance of mangroves as a defense against scourges like Yolanda was illustrated in the cases of two barangays, Parina and Bacjao, in the Municipality of Giporlos in Leyte.

Both were battered by Yolanda but were affected differently. Only 25 damaged houses were left standing in Bacjao, while Parina, which is nestled between two large mangrove forests, escaped with little damage.

Apart from serving as buffer against storm surges and tsunamis, the mangroves’ root systems serve as nurseries for many species of fish that go on to populate coral reefs. They also sequester three to five times more carbon per equivalent area than other types of forests and thus play an important role in ameliorating climate change.

Worldwide, mangrove destruction is rampant, with depletion going at a rate of about one percent per year. A pivot point to arrest this trend is needed, and Sri Lanka may have just provided it.

In a recent media briefing in Colombo, U.S.-based NGO Seacology; Sri Lanka-based NGO Sudeesa (formerly known as Small Fishers Federation of Lanka); and the government of Sri Lanka announced a joint program that will make the country the first in the world to comprehensively protect all of its mangrove forests.

The project which will cost US$ 3.4 million over the next five years will protect all 21,782 acres (8,815 ha) of Sri Lanka’s existing mangrove forests by providing alternative job training and microloans to 15,000 impoverished women who live in 1,500 small communities adjacent to this nation’s mangrove forests. The project will also replant 9,600 acres (3,885 ha) of mangrove forests that have been cut down. In exchange for receiving these microloans to start up small businesses, all 1,500 communities will be responsible for protecting an average of 21 acres of mangrove forest. A first-of-its kind mangrove museum to educate the public about the importance of preserving this resource will also be constructed as part of this project.

Sri Lanka President Maithripala Sirisena stated, “It is the responsibility and the necessity of all government institutions, private institutions, non-government organizations, researchers, intelligentsia, and civil community to be united to protect the mangrove ecosystem.”

“I highly appreciate and admire the joint effort made by the international non-governmental organizations Seacology and the Small Fishers Federation of Lanka to conserve the mangrove ecosystem of Sri Lanka,” he said.

Vanishing mangroves

Philippine mangroves have a painful story. In a 2000 study, of the 400,000 hectares of mangroves recorded in 1918, scarcely one fourth was found to remain.

Mangroves are still a favored source of building materials and charcoal, but aquaculture remains the major reason for depletion. Although there are still significant mangrove areas left, some provinces like Iloilo have up to 95 percent of what were once mangrove areas converted to ponds.

There are silver linings still.

As cited by Drs. Chandra Giri and Jordan Long in a 2011 paper, the greatest mangrove forest areas are located in Palawan and Sulu provinces, and the largest continuous strand of mangrove in the country, roughly 4,947 hectares, is located on the northwest coast of Siargao Island in Surigao del Norte.

However, from 1990 to 2000, total mangrove area decreased 10.5 percent, equivalent to 28,172 hectares, at an annual rate of 0.52 percent. The greatest decreases occurred in the provinces of Zamboanga Sibugay, Palawan, Zamboanga del Sur, Bohol, and Negros Occidental.

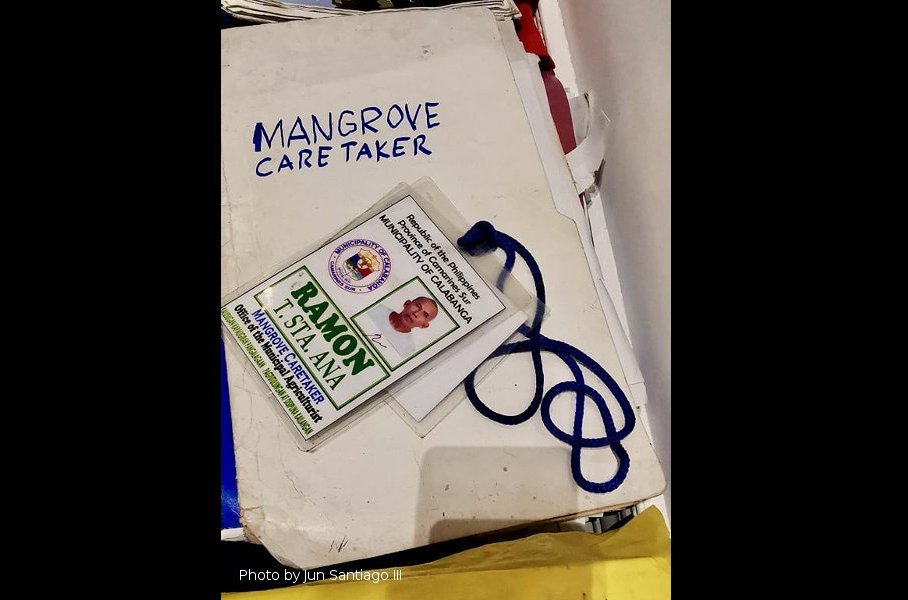

It is not easy. Successfully saving and rehabilitating Philippine mangroves will take an unwavering political will and enlightened community participation, tempered by inputs from scientists and academic institutions.

Yolanda was a very loud wake-up call, and it would be naive to think that another one would not be forthcoming. It may be a good time to take a page out of Sri Lanka’s playbook.

Ferdie C. Marcelo is the Field Representative for the Philippines of Seacology, a nonprofit based in Berkeley, California whose mission is to work with islanders around the world to protect threatened ecosystems.