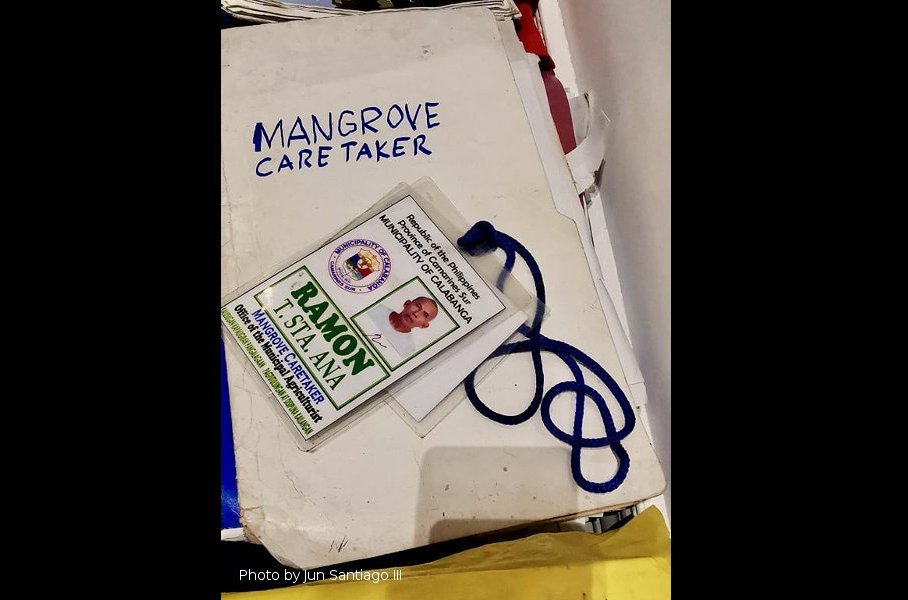

Ramon Sta. Ana, 67, could barely talk. Six successive strokes permanently damaged his speech motor, leaving the former barangay captain dependent on interpreters for communication. His sentences are slurred. But whatever voice is left of him, the 67-year-old mangrove caretaker is dedicating it to the protection of the environment.

Santa Ana, or Mon to his family and friends, was a former captain of barangay Cagsao in the coastal municipality of Calabanga in Camarines Sur. Although his chairmanship ended in an election loss in 2013, the residents still call him “Kap”.

Cagsao lies in the typhoon path of the Bicol region. On sunny days, the sleepy town’s black sand is littered with seashells, which, during low tide, produce chime-like music as waves lap the shore. At high tide, a battering sound of waves pounds the boulders of the mountainside walls like a canon.

Cagsao is practically unheard of except for disasters and its 10-hectare mangrove forest that was planted in 2007.

In the mornings, the towering trees and their gigantic roots are abuzz with fishermen and children looking for fish and shells to catch. At night, it’s a sight to behold with fireflies lighting up the rural darkness. If it weren’t for garbage improperly disposed of, the site is a perfect location for romantic films.

Calabanga is infamous for hellish disasters. The town located 405 kilometers south of Metro Manila is part of the typhoon belt in the Bicol region of southern Luzon. It battles multiple storms annually that bring its villages, including Cagsao, down to their knees.

In 2004, several storms passed through Calabanga. Three successive typhoons lashed Calabanga, leaving the village battered and weary. Since then, climate change became a catchphrase for the barrio folk who suffered from the natural calamity.

As disaster after disaster barrel through his town, Mon asked himself: What can be done?

In 2007, Mon found out that a non-government organization backed by the European Union was helping Calabanga’s three littoral barangays – Punta Tarawal, Balatasan, and Balongay- reforest their shorelines with mangroves. Like Cagsao, these villages were constantly affected by flooding and storm surges.

When Kap heard this, he convinced the project implementers to include his barrio. Awed by Mon’s passion and sincerity, the organization said yes. How could they say no to the passionate old man who was desperate to uplift the lives of the people in the Cagsao?

There began his uphill battle for the protection of mangroves. Mon faced resistance after resistance from the townsfolk, who thought mangroves were not the solution to their common curse.

Fisherman Jose Posada was quick to thumb down Mon’s plan. A skeptic Posada stressed that the project was bound to suffer the same fate as the failed reforestation attempts in the past. “Taon-taon naman nagtatanim wala namang nangyayari (Every year, we plant, nothing happens),” Posada said.

But Mon stood firm in his belief. The voters’ cold reception to his unpopular stand did not deter him from carrying out his vision. Instead of a defeatist attitude, Mon launched an information drive to explain why mangroves are the villagers’ best defense against storms and the best guardians of San Miguel Bay.

Cagsao used to have its own mangrove belt before men deforested the area. When the shore turned into the barren land, the community became at high risk of disasters.

While campaigning for the project to push through, Mon suffered a fourth stroke, which further damaged his speech motor. But Mon was unstoppable. He visited homes to convince the public about the benefits of mangroves. Through interpreters, the barangay captain unwaveringly explained how the forest is a natural buffer against disasters. And added that mangroves would provide the fishing community economic benefits because their roots serve as a nursery to marine life.

The people were slowly convinced. In April 2008, the adults and children joined Mon in planting the initial 150,000 propagules. His critics, like Posada, eventually became forest caretakers, too.

Mon’s battle to protect Mangroves continued. Two years later, a group of fishermen asked for a “right of way” so they could conveniently dock their boats. The request meant cutting several young mangroves, which, at that time, was just beginning to entrench its roots.

Mon said “No” and passed an unpopular ordinance penalizing the cutting of mangroves.

In 2013, Mon ran again and lost.

Four years later, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) approved the cutting of young mangroves to pave the way for an “eco-tourism” site that resembled the famous bamboo forest in Kyoto, Japan.

Several mangroves were taken down to build a bamboo bridge and resting hut in the middle of the plantation. This attracted an unregulated number of tourists and visitors. It created a buzz and turned Cagsao into an online hit.

The forest attracted vloggers, who talked about the mangroves’ beauty but not its destruction. Ironically, most vlogs on Youtube called for the protection of these trees while standing on a destroyed plantation that was built for tourists.

The bridge that connected man and mangroves fell after three years, and the eco-tourism site shut down. The once “instagrammable” tourist attraction is now a useless garbage at the heart of the forest.

Even villages wouldn’t dare cross the bridge. Against Mon’s advice, the bamboo pathway was built using metal nails that were not easily visible, especially in mud-filled lands where the plantation stood. And residents are wary of accidentally stepping on them.

This pains Mon, who felt the eco-tourism project came too soon.

“Napa-kabata pa ng mga mangroves ng umpisahan ang eco-tourism project. Ang mangroves ay para sa storm surges sana, hindi para sa isang tourist attraction (The mangroves were so young when they started the eco-tourism project. Mangroves are for storm surges not a tourist attraction,” he said through interpreter Armando Torres.

Mon never made a comeback in politics but he continued to watch over the forest as a mangrove caretaker. Despite years in public service, he applied for the job without fanfare. Humility never escaped him as he proudly wears his caretaker ID.

The former barangay chieftain had no qualms picking up the pieces of garbage that littered the sea and hung on the roots of mangroves as if they wereChristmas tree decorations

Some forest visitors recklessly hold tree planting activities at the mangrove site without consideration for the type of species that the area needs. Each time, Mon carefully plucks them out and replant them where they can survive.

He also religiously submits accomplishment reports to the DENR and never fails to remind them that what Cagsao needs is a second wave of mangrove reforestation.

Mon has yet to hear from the DENR. Mon feels like no one believed his vision just like the doomed Greek goddess Cassandra.

Looking at the mudflats in an interview earlier this month, Mon said: “Ito ang sinasabi kong malawak na lugar para muling pagtaniman, pero walang naniniwala. Noong umpisahan ang site na iyan ay ganundin naman hindi daw mabubuhay at matagal pa bago mapapakinabangan, sayang lang ang resources”.

(This is what I said is a large area that we can plant again but nobody believes me. When I started that site, that’s what they said; that they will not grow and it will takle time before they can be of use, it would just be a waste of resource.)

Mon has always loved agriculture and the sea as a young man. But his father, a fisherman, did not want Mon to end up like him. So he sent Mon to Manila for a university degree. But after finishing accountancy, Mon went back to the barrio to do what he loved to do: serve nature and humanity.

Months before the March 2020 pandemic lockdown, another bad news reached Mon’s doorsteps. Incumbent barangay officials passed a resolution demanding the demolition of a mound that sprouted near the seashore because the piece of land was blocking the fishermen’s route to the sea.

Mon vehemently opposed the proposal. This time, he had the mayor’s backing. “Hindi yan aalisin (That would not be taken out),” Torres said, quoting Mayor Ed Severo who rejected the whims of the new barangay council. “Kalikasan ang naglagay, kalikasan ang mag-aalis (Nature put it there, nature will remove it).”

The piece of land that the fishermen petitioned to remove turned out to be a moor or a natural sea wall that the mangroves created through time to protect the community from the punishing whip of storm surges.

The Tapar family, who had experienced nightmarish disasters in the past, said they have stopped evacuating ever since. The plantation’s success improved the fisherman’s catch, too. The site benefits academe as it serves as outdoor classroom for students and environmentalists alike. The local government now prides itself as a protector of the environment. And international nongovernmental organizations are tapping each other’s back for a job well done.

Mon does not compete for credit.

Mon said caring for the mangroves is his last testament to the barrio. He might have lost the elections but in looking after this forest, his constituents win.

*The author is a member of Congregatio Sanctissimi Redemptoris (CSsR) and a freelance photojournalist. This photo essay was produced with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network (EJN) and Photojournalists’ Center of the Philippines (PCP)