Mang Onad- Bantay Dagat volunteer

Mang Onad has been a tour boat operator for the past 20 years and

business has gotten better since he started.

He rents out his boat, The Kilyawan, to scuba divers normally for

P3,000 per trip, taking them to sites in Mabini and Tingloy towns, in

Batangas province. He jacks up the rate slightly for guests who want

to go to the southern side of Maricaban Island or to Verde Island,

also in Batangas.

That’s because Mabini, Tingloy, and Maricaban are among the most

popular dive spots in the area. They are so popular among scuba

diving that five or more dive boats can sometimes be seen in the same

dive spot; this is above the capacity that an anchoring bouy can

accommodate.

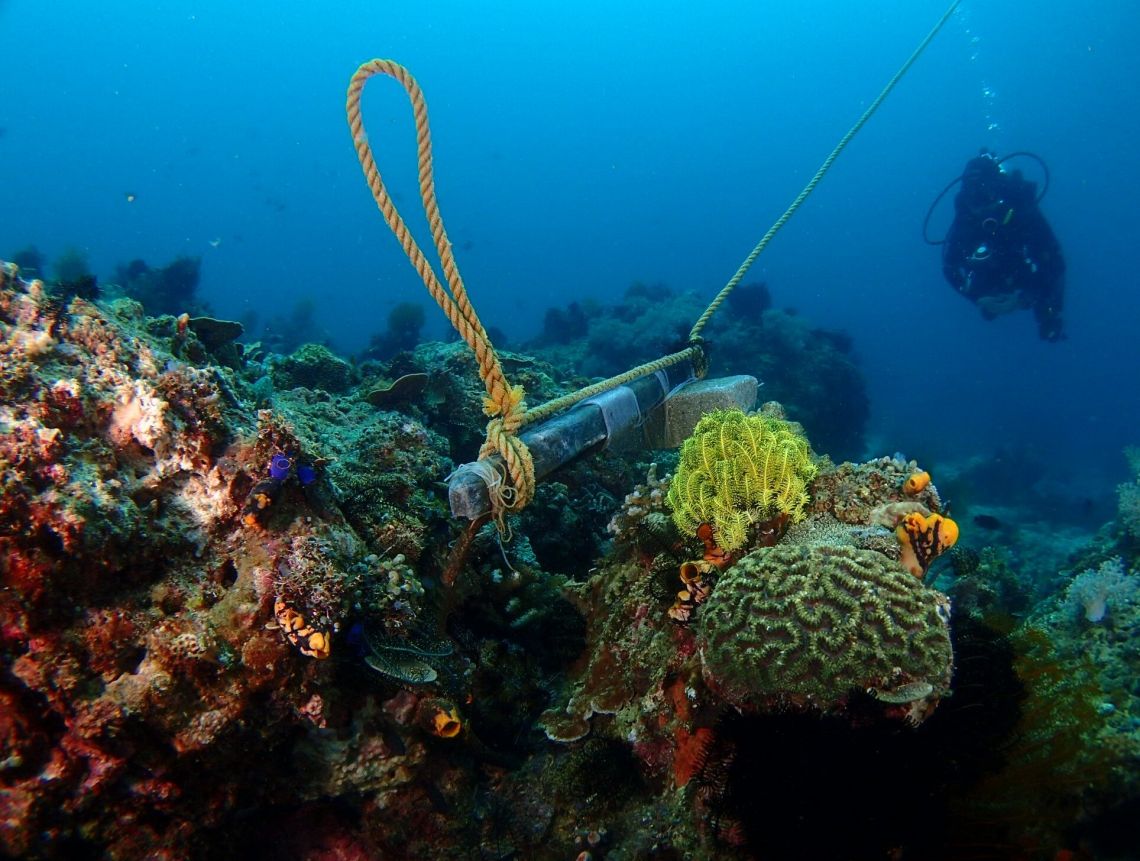

This leads to a problem. When the buoy can no longer accommodate a

boat, the boatman will need to drop anchor, which then damages the

corals.

Bad practice: Anchor dropped in Maricaban corals.

This destructive practice is expected to get worse as more people

troop to the beach and the sea to beat the summer heat.

The Batangas Provincial Tourism and Cultural Affairs Office

expects tourist arrivals to exceed 11 million this year. Mabini and

Tingloy – about a three-hour drive from Manila by car (and a boat

ride in the case of Tingloy) – are popular tourist destinations for

residents of Metro Manila.

Tourism vs environment protection

Locals like Mang Onad are ambivalent towards the avalanche of

visitors.

More tourists mean more income. But, at the same time, they are

aware of the damage a careless snorkeler, a novice scuba diver, or an

irresponsible visitor can cause especially to underwater sites.

Fishing had been the traditional source of livelihood for locals

up to the 1980s. But commercial fishing operations entered the area

and, with their lift nets or basnig /basnigan, took the lion’s

share of the catch closer to the reefs.

Dwindling catch forced local fishermen to venture farther and

farther out to the high sea. Many even resorted to dynamite fishing.

In the early ’90s, as word got out about Tingloy and Mabini’s

beautiful beaches and splendid ocean floor, tourists started

trickling in. They hired dive boats and rented rooms. These days,

they come in droves.

The influx of tourists is an economic bonanza for the communities

but it is taking a heavy toll on the environment.

A photo of Masasa Beach in Maricaban Island during Holy Week last

year went viral, not for the white sand or captivating scenery but

for the huge crowd that filled almost every inch of the beach.

These same visitors left piles of garbage. There is no landfill

site in Maricaban. Mabini town has refused to accept its neighbor’s

trash as it was also burdened with its own.

Coral reefs are the major casualty.

Tourists have stepped on corals. Some snap off a piece to take

home as a souvenir, not realizing that corals are animals and that

they could die when you cut off a piece.

It is apparent that many tourists are ignorant of the role of

coral reefs in the ecosystem. Corals are home to 25 percent of all

ocean’s marine life. When corals are destroyed, the marine population

are deprived of their habitat endangering their existence.

Coral reefs also provide an important barrier against the ravages

of storms, hurricanes, and typhoons. The storm surge that killed over

6,000 during typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan) would not have been as

destructive had the coral reefs in Leyte been healthy.

Early attempts at conservation

Some four decades ago, when dynamite fishing was rampant in Mabini

and Tingloy, divers would hear the blasts while diving. The boatmen

were unaware because sound travels four times faster underwater than

at the surface.

Concerns for the deteriorating marine habitat encouraged concerned

divers to initiate the installation of artificial reefs made of used

tires. They copied a program that was already in place in Florida.

Corals on old tire in Mabini’s ocean floor.

This waste management and conservation program continued well into

the mid-1980s until it was found that the rubber tires were doing

more harm than good.

Constant water motion caused the bindings to loosen and snap,

scattering the tires and damaging natural reefs in the vicinity.

Also, tires contain black carbon, sulphur, zinc oxide, and other

chemicals that inhibit coral growth.

Fortunately the passage of time has a way of dulling, if not

correcting, mistakes.

Forty years later, most of the tires have already settled in the

sand. The harmful chemicals seem to have all but dissipated, turning

them into a more palatable substrate for coral larva to finally

attach and grow.

There is no more dynamite fishing in the area, said Mang Onad who

is also a Bantay Dagat volunteer, a sort of fish warden.

Compressor diving

Local environmental watchers have to deal with another kind of

problem–the occasional compressor diver.

Compressor diving involves the use of refurbished compressors from

discarded air conditioners or refrigerators attached with a long tube

which the diver bites in place so he is fed air while underwater.

He

then positions a wide net where fish are schooling and signals his

accomplices to pull up at the right time. The practice depletes the

fish stock. It is also harmful to the diver because residual oil from

the unfiltered air will likely lead to respiratory disease.

Mang Onad recalled that he recently got a call from his fellow

Bantay Dagat volunteers about compressor divers in one of the reefs.

It was 1:30 in the morning.

Mang Onad and his team promptly proceeded to the site and trained

their lights on the poachers who quickly dispersed.

There were prior incidents where the Bantay Dagat volunteers would

apprehend the divers themselves and turn them over to authorities.

The Parasan Marine Protected Area

The awesomeness of a squid.

Underwater splendor in Tingloy: Shrimp in bubble coral.

Lessons from the past are not lost on the community of

Tingloy.

On Novermber 26, 2018, the municipal council

passed an ordinance declaring the 22-hectare reef in front of Masasa

Beach in Barangay San Juan as the Parasan Marine Protected Area.

The ordinance sets aside a core zone where no marine resource

extraction, including fishing, is allowed and provides the legal

basis for the apprehension of violators.

With the assistance of Pusod, an NGO supporting the area,

community members have been mobilized to monitor the reef and its

environs. Some were trained in free diving to help compile data and

to orient and guide visitors on how to best appreciate the reef

without causing damage.

Additionally, Tingloy was able to secure a grant for the

construction of a Nature Conservation Center from Seacology, a small

NGO based in Berkeley that provides funds for communities willing to

care for their natural resource.

Plans are also afoot for the construction of a Materials Recovery

Facility to support waste management efforts.

Political will counts a lot but any program still requires the

cooperation of the people. The Conservationists’ Golden Rule

remains the best guideline: “Take nothing but pictures, leave

nothing but footprints, keep nothing but memories.”

(The author, Ferdie C. Marcelo, is the Field Representative

for the Philippines of Seacology, a nonprofit based in Berkeley,

California whose mission is to work with islanders around the world

to protect threatened ecosystems. This story is produced by VERA Files under a project

supported by the Internews’ Earth Journalism Network, which aims to

empower journalists from developing countries to cover the

environment more effectively.)