It could have been the first ever public documentary of the Marcos family plunder and it was aired on American television. The program Frontline, hosted by Judy Woodruff and aired by a network of public television channels across various cities in the United States, produced a scandalizing documentary that narrated how Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos bled dry the coffers of the Philippine government to amass wealth that rivaled many of the world’s rich and famous.

“In Search of the Marcos Millions” aired in May 1987, just 15 months after the conjugal dictators were ousted from power.

“Marcos, his family, friends and cronies, had for two decades looted the Philippines of hundreds of millions of dollars,” Woodruff began. How were they able to accumulate such a massive private fortune?

The documentary traced the available paper trail to where the Marcoses hid their wealth. It also included direct interviews with the dictator himself from his home of exile in posh Makiki Heights in Honolulu, Hawaii.

The documentary showed footages of U.S. congressional hearings where the Bernstein brothers, real estate agents in New York City, testified on how Imelda bought several Manhattan skyscrapers. “In a country where 70% of the population live below the poverty level, the ostentatious wealth of the Marcoses and their unseemly corruption clearly contributed to the national revulsion against them,” said U.S. congressman Stephen Solarz.

At that time, the Philippine government had already discovered the Marcos accounts in Swiss banks. On that euphoric night of February 25, 1986, the bank documents were found in a safe cabinet at the Malacañang Palace.

One in particular was a smoking gun. It was a specimen signature form of the William Saunders and Jane Ryan accounts which the autocrats signed below these aliases with their own hand. But that was not all.

On that night when angry mobs stormed the palace, they found plates of uneaten caviar on the dinner table, hundreds of empty jewelry boxes, and crates of millions of newly-minted cash. The fleeing family had apparently tried to hide any paper evidence. In the communications room, three shredding machines had jammed.

After the mobs had left, an aide of the new government named Chito Roque went to Malacañang. All alone, he walked around the rooms the Marcoses had just hurrily vacated. In the dictator’s bedroom, Roque found several medical equipment.

“It was like a hospital,” he related. The room stank of the dictator’s feces.

Then the aide saw a filing cabinet. He opened the top drawer and to his surprise, the combination of the lock to the safe was taped inside. The next morning, more documents were found in the secret vault containing information on bank accounts in Hongkong, Switzerland and the U.S.

In the documentary, the dictator maintained the signature on those bank documents were forgeries. “There is no document that said these documents existed because of me,” Marcos insisted.

But actual events did not match the dictator’s alibi. In fact, “a most unusual visitor” visited Switzerland less than four weeks after the Marcoses had fled the Philippines. Michael de Guzman, a Filipino businessman, had come from Hawaii.

By this time, however, Swiss authorities had been alerted about the Marcos stash in their banks. They had recorded everything.

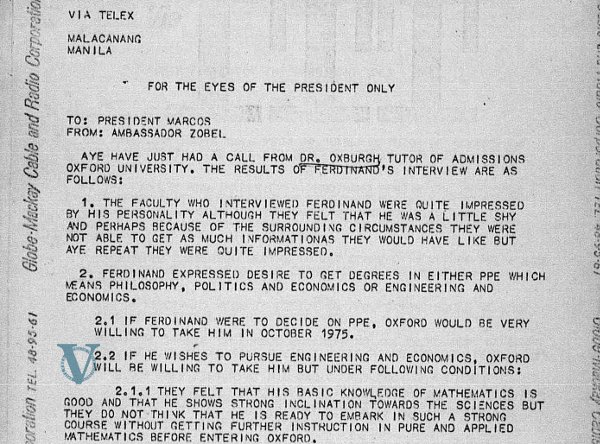

How did they know that Marcos was sending De Guzman?

The bank, Credit Suisse, had received a phone call prior to De Guzman’s visit. It was Bongbong Marcos on the line. The dictator’s son informed the bank authorities that De Guzman would make a withdrawal in the amount of $213 million in cash.

De Guzman produced two identical documents with instructions to “Please hold all securities and cash at the disposal of Michael de Guzman who will present this letter to you in person. He will identify himself by presenting his passport.”

One was signed Ferdinand E. Marcos; the other Imelda R. Marcos. Bank officials told De Guzman to come back the next day. Unknown to the Marcoses, the bank treated this as a tip and acted fast. It called the Federal Banking Commission.

Daniel Zuberbuhler, vice director of the Commission, received the call. He contacted Switzerland’s state officials who happened to be in Bern attending a banquet that night. The call prompted them to hold an emergency huddle in the middle of the dinner.

During that banquet, an announcement was made that remains unprecedented to this day. The Swiss government had decided to freeze all Marcos bank accounts. All banks that held Marcos accounts were ordered to stop the release of any amount without prior approval of the Commission.

In the documentary, Zuberbuhler confirmed that the Marcoses had accounts in Swiss banks.

Take note: the Philippine government made no formal request to the Swiss government to freeze all Marcos accounts. It was a decision reached solely by Switzerland because of a worldwide concern, after the disgraceful fall of the Marcoses, about the use of its banking system to hide dirty money.

Bongbong Marcos’s telephone call foiled the attempted withdrawal by his father. In the process, he revealed to Swiss authorities his participation and interest in the concealment of stolen money.

There is no need to waste a lot of words. The Marcos plunder was a family affair. The facts contradict the historical redemption the heirs now desperately desire. The dictator’s only son, his namesake, sinned as the father had.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.