Entrance to the Ati Community Village in Manok-manok

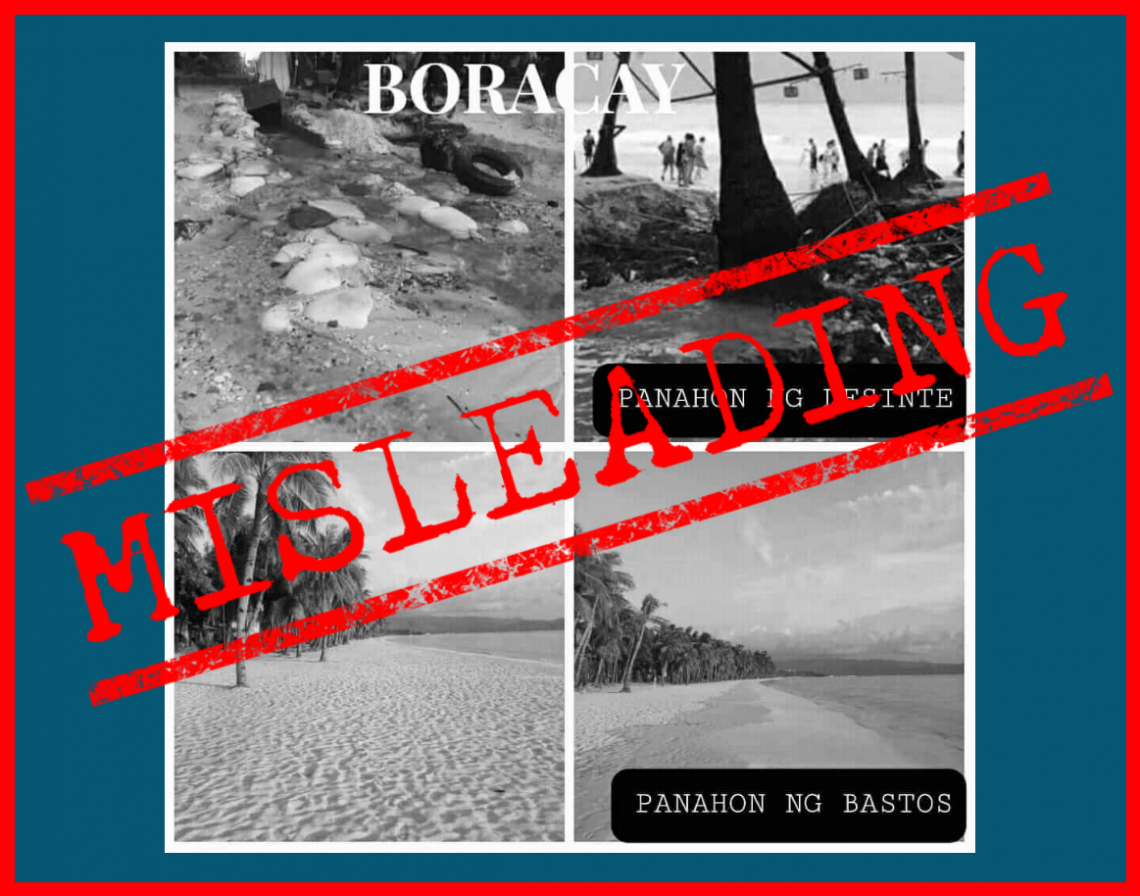

BORACAY ISLAND – Upon entering the unlocked gate of the Ati Community Village in Manok-manok, a row of bamboo houses with concrete base meets the eye of the visitor, while the playful laughter of children can be heard. Two cheerful Ati teen girls curiously pass by. An elderly man with a cane sits on a chair nearby.

Three women leaders of the Boracay Ati Tribal Organization (BATO) quietly positioned themselves on the step of one of the sawali or bamboo houses as they took turns in narrating life as their ancestors had lived it in Boracay, belying claims that no Atis had lived on the island early on.

Tribal chieftain Delsa Justo, in an interview with Vera Files ahead of Boracay’s reopening, said that a total of 234 Atis live in the community compound built on land covered by a Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT). It was awarded on January 21, 2011 but part of that land is being contested.

As the world-renowned tourist island reopened on Oct. 26 after a six-month cleanup, the indigenous community that had lived on the margins could also make a fresh start as the government carries out its blueprint to improve their lives.

As part of the rehabilitation of Boracay, President Rodrigo Duterte has said he would turn the island into a land reform area and return it to the natives. He even said that he would personally hand them their certificates of land ownership.

According to the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR), eight cadastral lots covering 7.9 hectares in Manok-manok, a barangay in Malay town, are being prepared for distribution to “indigenous farmer beneficiaries” in December.

Kids with fishing net on a beachfront

DAR Assistant Regional Director for Operations Gideon Umadhay was reported by local media as saying his office can now “roll out with the land distribution” with the Ati farmers as primary beneficiaries based on the certified list provided by the National Commission of Indigenous Peoples.

“There will be identification and screening but we are prioritizing the tribes coming from Boracay,” regional tabloid The Daily Guardian quoted him as saying.

“For the Atis, land is life. It is where we get our food. Without land, there would be no Atis,” 58-year-old Justo explained in Filipino. “But the forests are gone and there are lots of people, many tourists, and people who are claiming the land,” she lamented.

The community occupies only a portion of the 2.1-hectare ancestral property on the 1,032-hectare holiday island because of land ownership disputes with families and businesses in the area.

The disputes pose a serious threat to the indigenous community, and Justo hopes Duterte’s declaration that land will be returned to the natives will be clear to all.

On two separate occasions in 2012, the Atis were harassed and threatened by men identified with resort owners contesting the land award, and local officials who were opposed to the Atis getting the land, according to Vangie Tamboon, another Ati leader. The landowners told the Atis they had bought the property and that “Boracay is only for business” so they should leave the place, she related.

Then on February 22, 2013, Dexter Condez, 26, an outspoken youth leader and spokesman of the indigenous organization BATO, died after being shot six times by a then unknown assailant as he was walking with two female companions after attending a meeting.

Common afternoon pastime: Hinguto (searching for and removing of hair lice).

Condez was at the forefront of the Ati struggle to assert their ancestral rights over their land, the Ati women told Vera Files.

His killing has yet to be resolved, even as a suspect, a security guard working for a major hotel on the island, was arrested in 2014, with motive still to be established.

The Ati leaders, however, maintained that

Condez was killed “because he faced those who wanted to get the Atis’ land.”

Holding back tears, Tamboon said in Filipino: “We thought our world would fall apart but we did not stop to fight for our rights.”

The community of only 42 families has been struggling for over 10 years to secure their Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT). But when the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) finally granted them the title to 2.1 hectares in 2011—the smallest certified ancestral domain in the world!—other land claimants continue to contest the Atis’ peaceful residence,” wrote Chaya Go in an article published in the Aboriginal Portal of the University of British Columbia (UBC).

“Why is it so difficult for over 200 Atis to live well, and without discrimination, in such a small portion of land? The Atis continue to grieve for the murder of their brother, and for their ancestral land,” she said.

Recalling the days before the island became a bustling commercial area, Tamboon, 39, said in Filipino: “Our ancestors roamed the island, catching fish in the river and sea, hunting for deer, wild boar, stray cats.” They used bows and arrows and blow guns in hunting with the help of dogs, she said, adding that birds, wild pigs, monitor lizards, and wild cats were the traditional catch.

Not many visitors know that the resort island in Aklan province famous for its powdery-white sand beaches is the ancestral land of the Ati community, people who have called the island home since time immemorial.

Boracay is sacred ground for the Atis

“Underneath the sprawl of hotel-resorts are the Atis’ burial and sacred grounds found all across the island, said Go, a UBC anthropology graduate. “Even the word ‘Boracay’ … is a name the Atis’ ancestors gave the island in the Inati language,” she wrote in a 2013 published in the UBC Aboriginal Portal.

The Atis had two burial areas at Hambaludan near the sea in Yapak village, 39-year-old Tamboon shared.

As late as the 1960s, Atis in the area were still nomadic and gathered wild fruits, tubers, honey and vegetables that grew wild in forests for their food. They lived in makeshift shelters with grass roofs and split bamboo floorings.

This nomadic existence had been abandoned due to deforestation, pressure from lowland and migrant population, and later expansion of mostly tourism-related business activities. Many Atis, were in fact, driven up to the interior forests in the province.

These days, visitors will see Ati men loading goods or working as utility men in tourist establishments, while some women sell trinkets and traditional medicine, work as house help or raise animals to sell for additional income. A multi-purpose cooperative run by the community is engaged in bath soap-making, sewing and handicraft making.

Vangie Tamboon says they will fight for their land

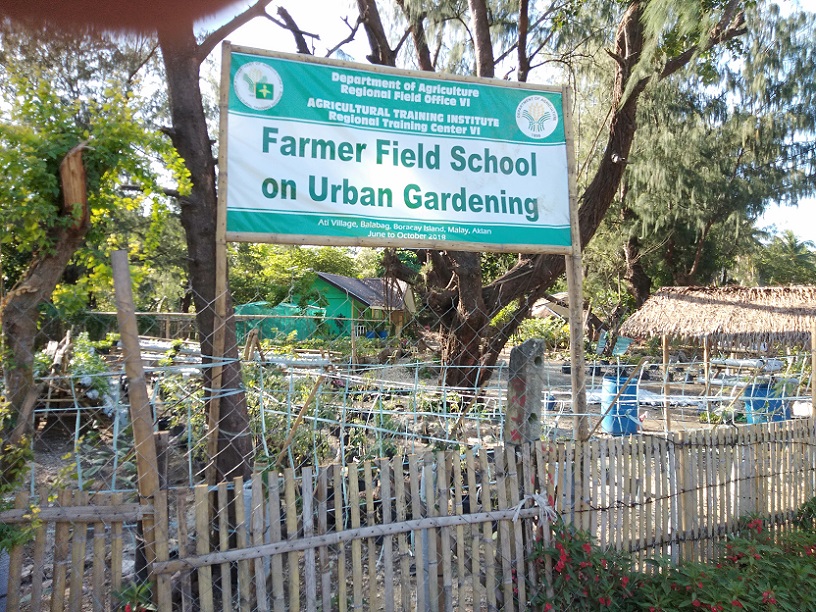

Some Atis are under the government’s cash for work assistance program in some road projects as part of the island’s rehabilitation. The government also started an Urban Gardening Project as assistance for the community when Boracay was shuttered.

Another Ati leader, 43-year-old Leonida Bartolome, recounted how simple their lives were in the past. “We used to go to different parts of Boracay. If we found sweet potatoes, vegetables, coconut, fish, we could live on that. No problem,” she said in Filipino.

“We were not here? They are the ones who are not native to this place,” she insisted, questioning claims by local officials that the Atis are not indigenous to Boracay.

In ancestral domain areas, indigenous people are allowed to hunt and eat whatever animals or plants they are culturally accustomed to using for their own consumption.

Today, many Atis in the village only have plain coffee in the morning, nothing more. Lunch consists of rice with some fish or vegetables, and dinner usually consists of rice with sardines or noodles. They do not have snacks, the Ati women shyly shared.

The Atis in the Panay region have been baptized into various denominations of Christian religions, like the Roman Catholic and Baptist churches, but many still practice traditional beliefs and rituals they inherited from their ancestors. They also have some knowledge of medicinal plants.

The Ati community on Boracay island has been under the care of the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul. It has also been supported by the Assissi Development Foundation Inc., a private non-profit organization that supports the indigenous people with various development projects.

First inhabitants on Panay Island

Anthropological studies have established that indigenous Ati people were the first inhabitants of Panay with the migration of the Negritoes. Panay region in the Western Visayas includes the provinces of Aklan, Capiz, Antique, and Iloilo.

The Atis are genetically related to other Negrito ethnic groups in the Philippines, such as the Aeta of Luzon, the Batak of Palawan, the Agta of the Sierra Madres and the Mamanwa of Mindanao.

Urban Gardening Project for the Atis

The latest population count shows that there are 22,837 Atis in Panay and Guimaras.

Back in the 1970s, when Boracay was still a well-kept secret of cognoscenti travelers, visitors to the island stayed with the villagers, or in makeshift bamboo huts, that way they experienced the lifestyle of the island residents, who then depended almost entirely on subsistence fishing and agriculture, says the Boracay Foundation Inc.’s guide to the island.

Even that early, Panay had been known for its Ati-Atihan Festival, with the catchy “Hala Bira!” chant, which was inspired by the Ati culture and its musical beat and life rhythm.

While the Ati-Atihan Festival “gained worldwide recognition, and successfully maintained the tourist economy in Kalibo, and sparked a rich cultural identity, the globalization and modernization of the event has unfortunately led to the marginalization of the original focus of the event—the Ati people,” says Alyssa Lagat-Ramos through AuthorSTREAM (Summer 2014).

“Although it is good to move forward, we must always remember our roots and where we come from,” she concludes.

This story is produced by VERA Files under a project supported by the Internews’ Earth Journalism Network, which aims to empower journalists from developing countries to cover the environment more effectively.