It was the sixth birthday of Loreto Dencio’s youngest son, Russel Ian, but instead of celebrating it, Dencio rented a jeepney to claim the remains of his wife, Rosel.

Rosel was among the 33 passengers killed when the ill-fated Leomarick Trans bus plunged into a ravine in Capintalan, in Carranglan town in Nueva Ecija on April 18.

The families of those who died are left with nothing but memories, and a measly sum of money that cannot in any way compensate for the loss of a loved one.

On Maharlika Highway, a day after the crash, the midday summer heat was smothering. A long queue of SUVs, trucks, and public utility buses parked — some haphazardly — along a narrow, curved junction of Maharlika Highway, next to a hundred foot-deep ravine.

A throng of people looked intently at the bottom of the chasm. There were a few TV cameras in a sea of smart phones raised by curious onlookers. Selfie sticks raised in the air.

A middle-aged woman finger-combed her hair, her back turned to the ravine. She raised her phone, adjusted the front camera for a perfect frame, and snapped a photo.

This tourist spectacle’s main attraction was a piece of crushed metal with only a pair of wheels left.

A day before, parts of the squashed steel box were drenched in blood. Thirty-three dead bodies were strewn about. Forty-four severely injured people were rescued from the wreck.

The cry of a birthday boy

Two towns away from the crash site, in Aritao, Nueva Vizcaya, a funeral home located behind a rice mill was filled with people.

Unlike the onlookers along Maharlika Highway, the stares of the people waiting outside the mortuary were morose.

Loreto clung to a tree trunk next to a jeepney outside the funeral parlor. The jeepney would carry the body of Dencio’s wife, Rosel.

His shoulders were slumped, his loose purple shirt hanging from his thin frame. His eyes were red and puffy.

“Wala tayong magawa, ganyan na [There’s nothing more we can do, what’s done is done],” Loreto said. He cried silently.

He then spoke in Ilocano with the woman sitting next to him, Jeanette Dalay, his wife’s sister.

Sitting on Dalay’s lap was Russel Ian, Dencio’s son, the birthday boy.

“Kasi nagbabakasyon sa akin ‘yung dalawang anak niya eh. Pa-pasyalan niya sana kasi birthday ng anak niya ngayon eh. Pero ayan, hindi naman siya dumating,” Dalay said, struggling to keep herself from crying.

[Translation: Her two children were spending their summer vacation with me. She was supposed to visit them because one of the kids is celebrating his birthday. But she was not able to come.]

Rosel was supposed to bring vegetables as part of a dish for the celebration.

Russel Ian was also crying and throwing a tantrum. He violently shook his head, and pointed at the jeepney.

Loreto took Russel Ian from Dalay, and gave him a pat on his back.

Loreto said: “Kako, ‘Anak wala naman na si Mommy.’ Pero hindi niya man siguro naiintindihan.”

[Translation: I said, ‘Son, Mommy can never be with us anymore. But I don’t think he understands.]

White lace dress for Rosel

Rosel’s body was taken to a mortuary, a small, apple-green room, with ceiling panels hanging loose.

There, nine bodies were being cleaned. One cadaver was dismembered. Only a small part of the person’s right jaw was left. The stomach was ripped open. No one has claimed the body yet.

Three women holding each other walked in. One of them with graying hair wailed before a body on the floor.

Rice sacks covered some of the bodies reeking of chemicals. People were hustling their way in and out of the pungent room like it was nothing.

Loreto also went inside the room, and handed a white lace dress to the embalmer.

“Wala pa nga kami pambayad sa jeep na ni–renta namin, sir. Pang-cake lang ni Nakkong (son) yung naipon namin,” he said.

[Translation: We have no money to pay for the jeep we rented, sir. We only saved enough for the cake of our son.]

Loreto is a farmer who earns less than a thousand pesos every week. Rosel would sell some of his produce at the town’s market. Loreto said she took care of their children well.

“Sana’y may ibigay (na tulong). Salamat din kung ma–ibigay nila,” he said.

[Translation: We hope that we will be given help. We will be grateful for it.]

Loreto has lost control of his emotions. He sobbed like a child on his way out of the room.

The loss of a mother

Outside the mortuary, Dencio instructed his eldest child, Lorena Mae, to cover the jeepney floor with a white cloth.

“Sa paradahan ng jeep sa Dupax del Sur man kami nagkakilala noon (ni Rosel). Year 2000, kung hindi ako nagkakamali at 23 lang po siya noon.”

[Translation: Rosel and I met at a jeepney terminal in Dupax del Sur. It was in 2000, and if I’m not mistaken, she was only 23 then.]

Lorena Mae was born the following year. Now 17, she just finished her first year in college. She hopes to complete a degree in Secretarial Administration.

“Hindi po ako naniniwala na wala na siya [I do not believe she’s gone].”

It was her mother who found a way she could enroll in college, even if the family’s funds were meager. Rosel was the rock of the family, Lorena Mae said.

“Sabi niya ‘pag makatapos na ako, ipagawa ko raw bahay namin [She said when I finished school, I should get our house fixed].”

Lorena Mae said when they found out about the crash, the family hoped her mom had boarded a different bus.

“Ginawa namin lahat para kontakin siya. Lahat po ng kamag-anak namin ‘doon. ‘Yun nga po napatunayan na ‘dun siya po talaga.”

[Translation: We did everything we could to contact her. We got in touch with all our relatives there. Then we found out she was really onboard that bus.]

Standing by the jeepney door, Dencio said: “Wala man kami pera, sir. Doon na ako nagpagawa ng kabaong sa amin. D’yan namin siya ilalagay muna, pa-byahe pauwi.”

[Translation: We have no money, sir. I had someone from our town make her coffin. She will be laid there on our way home.]

Her life’s worth

On April 22, Loreto was among the relatives of the crash victims who received financial assistance from the government.

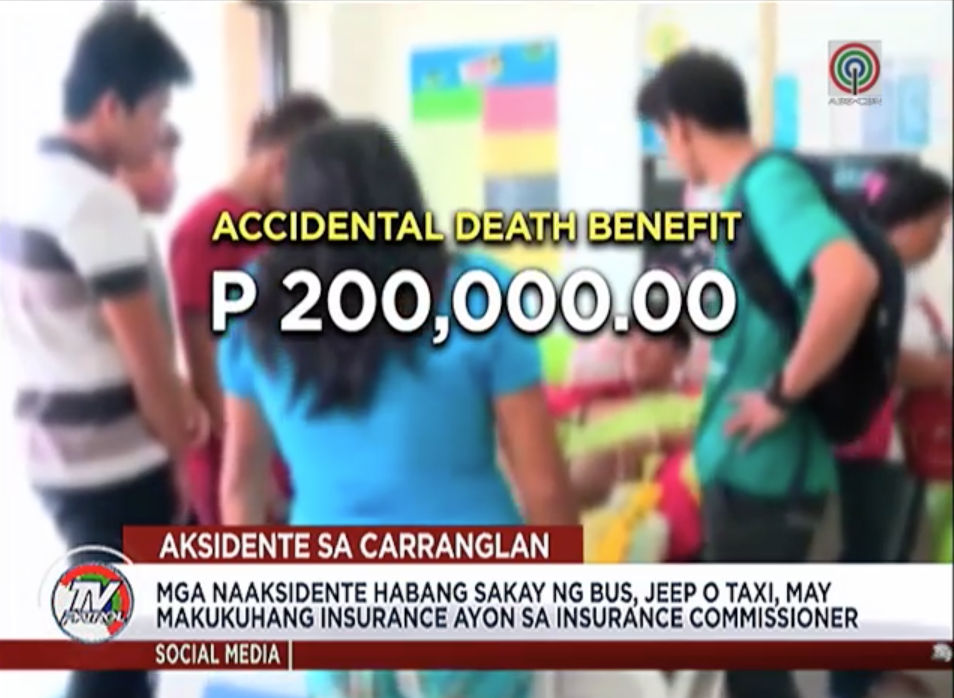

The insurance provider for public utility vehicles, Passenger Accident Management and Insurance Agency or PAMI, released ₱200,000 each to family members of victims who died in the crash, and ₱20,000 to those who were injured.

President Rodrigo Duterte extended an additional ₱20,000 to each victim.

“Medyo masakit isipin na ₱200,000 lang yung halaga ng buhay ng asawa ko [It’s a bit painful, sir, to think my price of my wife’s life is just ₱200,000],” Loreto said.

Through a memorandum order in 2015, the LTFRB raised the financial assistance given to public passengers killed in a crash to ₱200,000.

Before this latest memo, the coverage given for each death was at ₱150,000. This has increased through the years. In 1990, the financial assistance for death amounted to only ₱50,000.

For injuries, PAMI has also specified a set of financial coverage depending on the part of the body affected.

“Pero mabuti na ito kesa wala. Bakit pa ako magrereklamo? Para mailibing namin siya nang… maayos,” Dencio said.

[Translation: But this is better than nothing. Why should I complain? We can bury her properly.]

Rosel was laid to rest in a homemade casket on April 24, six days after the crash, in Dupax Del Sur, in Nueva Vizcaya, her hometown.

This story, first published on CNN Philippines, was produced under the Bloomberg Initiative Global Road Safety Media Fellowship implemented by the World Health Organization, the Department of Transportation and VERA Files.