IT is a surprise to most people to find a museum dedicated to General Emilio Aguinaldo in the northern Philippine city of Baguio. After all, Aguinaldo’s hometown is down south in Kawit, Cavite Province, where Philippine independence was declared 116 years ago.

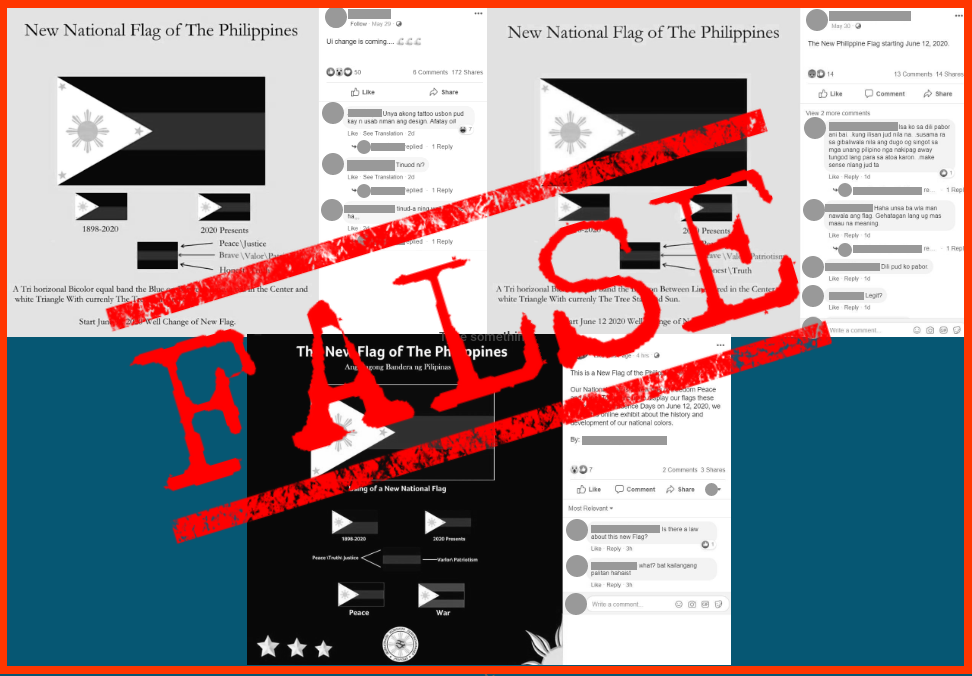

Located on Happy Glen Loop, not far from the city center, the museum looks more like a house. But it has one artifact that no museum — not even the Aguinaldo Shrine in Kawit — has: the very Philippine flag that was unfurled on that day in 1898.

Well, that’s what the museum’s curator and Aguinaldo great-grandson, Emilio Aguinaldo Suntay III, maintains. General Aguinaldo himself said so when he bequeathed the flag to his daughter, Cristina Aguinaldo-Suntay, shortly before he died in 1964.

That has yet to be authenticated by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines, however. But the story surrounding the flag is difficult to ignore.

Aguinaldo family legend holds that the flag was Aguinaldo’s favorite. He flew it in 1962 when President Diosdado Macapagal moved Independence Day from July 4 to June 12, and had kept it under his deathbed.

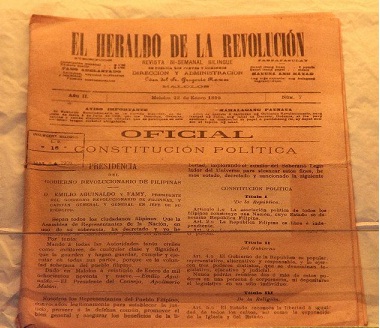

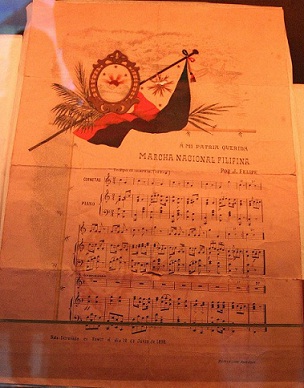

There are a few other notable artifacts at the museum. In a display cabinet is a copy of the Malolos Constitution, Asia’s first democratic charter, and a lyric sheet of Marcha Nacional Filipina, which was played in 1898 and is today the national anthem.

But it’s the flag that is the museum’s pièce de résistance.

Measuring 84 cm in length and 97 cm in width, the flag is encased in glass and kept in an air-conditioned room maintained at 25 degrees Celsius and under very low light to prevent the colors from bleaching. A nylon net keeps the flag together, clearly fragile from the passage of time.

History books narrate that the flag was commissioned by Aguinaldo and sewn by Marcela Agoncillo at her home on 535 Morrison Hill in Hong Kong. She was assisted by her daughter, Lorenza, and Delfina Herbosa de Natividad, a niece of Philippine national hero Jose Rizal.

It was that flag that Aguinaldo brought back with him from exile in Hong Kong and is now in Baguio, according to the Aguinaldo clan.

Suntay estimates the flag to have a shelf life of 50 more years. Rather than keep it in storage to preserve it, the museum prefers to display it to give Filipinos a chance to see it before it fades into history.

Suntay is careful not to present the flag as an Emilio Aguinaldo show, unlike most Filipino political families today who tend to glorify themselves and exaggerate their achievements. Instead, Suntay feels it his duty not to just be the flag’s custodian, but to enlighten Filipinos on what it represents — nationhood and freedom.

“The lack of a profound understanding of the triumph over adversity by our forefathers for their country leave us as a proud but shallow people, deprived of glory, patriotism and dignity,” Suntay says.

“It is therefore not illogical to conclude that the present-day Filipino is but a spoiled brat without regard or rightful sense of history and identity, whose forefathers handed down freedom and liberty on a silver platter.”

The issues that hounded the nation in 1898 are still very much around, he adds.

For one, there is the issue of national honor. One of Aguinaldo’s reasons for declaring Philippine independence was to improve his bargaining stance before US ground troops arrived in case the United States replaced Spain as the Philippines’ new colonial master following the Spanish-American War.

Washington ignored Filipino independence aspirations in the Paris peace negotiations with Madrid over the future of the Philippines. That put them on a collision course with the Filipino revolutionaries, paving the way for the Philippine-American War (1899-1902).

Fast forward to 2014, the Philippines is again facing territorial encroachment, this time from China. “Despite our past glory and greatness, we are now a nation divided, invaded and looked down upon by neighboring countries,” Suntay says. “For far too long, many of us have turned an apathetic eye to the threats against our sovereignty and to what ills our society.”

Then, there is also the never-ending bickering among Filipino politicians that often hinders national policymaking.

Rewind to 1897 at the height of the Philippine Revolution. Revolutionary leaders had convened in the town of Tejeros to resolve the factionalism that was splitting the Katipunan movement between its leader Andres Bonifacio and Aguinaldo, who was elected president of the newly declared Philippine Republic.

But Bonifacio voided the convention following a disagreement over election rules. He was ordered arrested by Aguinaldo and executed after a marathon trial for allegedly sabotaging the revolution.

That episode tainted Aguinaldo and his legacy, even beyond the grave. To this day, the passionate debate between Bonifacio and Aguinaldo admirers continue to boil — minus the drawn revolvers, of course.

Suntay acknowledges the controversy dogging his great-grandfather. But he also points out that it has also distracted Filipinos too much from understanding why the Philippine Revolution happened.

“For too long a time, many of us have wallowed in the futile and self-destructive debate of who among our heroes is best, who is worst, and what should have been,” he says. “Understanding and appreciating the true essence of our forefathers’ struggle for independence shall guide us in better managing our nation and posterity.”