The Association of Southeast Asian Nations starts discussions on a Code of Conduct in the South China Sea this month with two contentious issues: the non-militarization of occupied features, and restraint in the activities in the SCS, specifically those involving China.

ASEAN with the Philippines as chair leads these discussion, amid a situation that has not really changed and where the SCS remains an area of tension even with improved ties between two of its claimants, the Philippines and China, Philippines Foreign Affairs Undersecretary for Policy Enrique Manalo said.

“Of course our relations with China improved over the last few months but it doesn’t mean the situation has necessarily changed, not only from our perspective but even (from those of) the other ASEAN countries,” Manalo said. “So there is that challenge to ensure that when we have a framework.”

The Declaration on the Code of Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC), which was signed by all members of ASEAN and China on Nov. 4, 2002, lists the principles of self-restraint and non-militarization in Paragraphs 5 and 6.

Paragraph 5 partly states, “The Parties undertake to exercise self-restraint in the conduct of activities that would complicate or escalate disputes and affect peace and stability including, among others, refraining from action of inhabiting on the presently uninhabited islands, reefs, shoals, cays, and other features and to handle their differences in a constructive manner.”

Paragraph 6 enumerates non-military activities that parties concerned can undertake such as marine environmental protection and marine scientific research pending a comprehensive and durable settlement of the disputes.

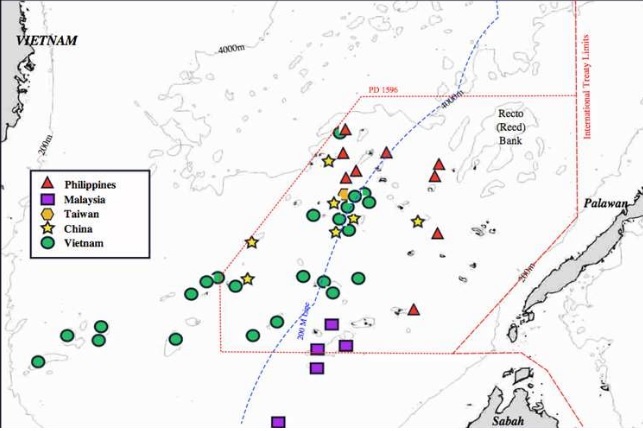

The 3.5-million-square-kilometer South China Sea has been the scene of conflict between countries with territorial claims in the area.

In 2014, Vietnamese and Chinese ships engaged in a water cannon battle when China placed an oilrig near the Paracels, site of a violent clash between China and South Vietnam (before the 1975 reunification of North and South) 40 years ago. The battle resulted in the sinking of a South Vietnamese warship and the death of more than 53 Vietnamese and 18 Chinese servicemen.

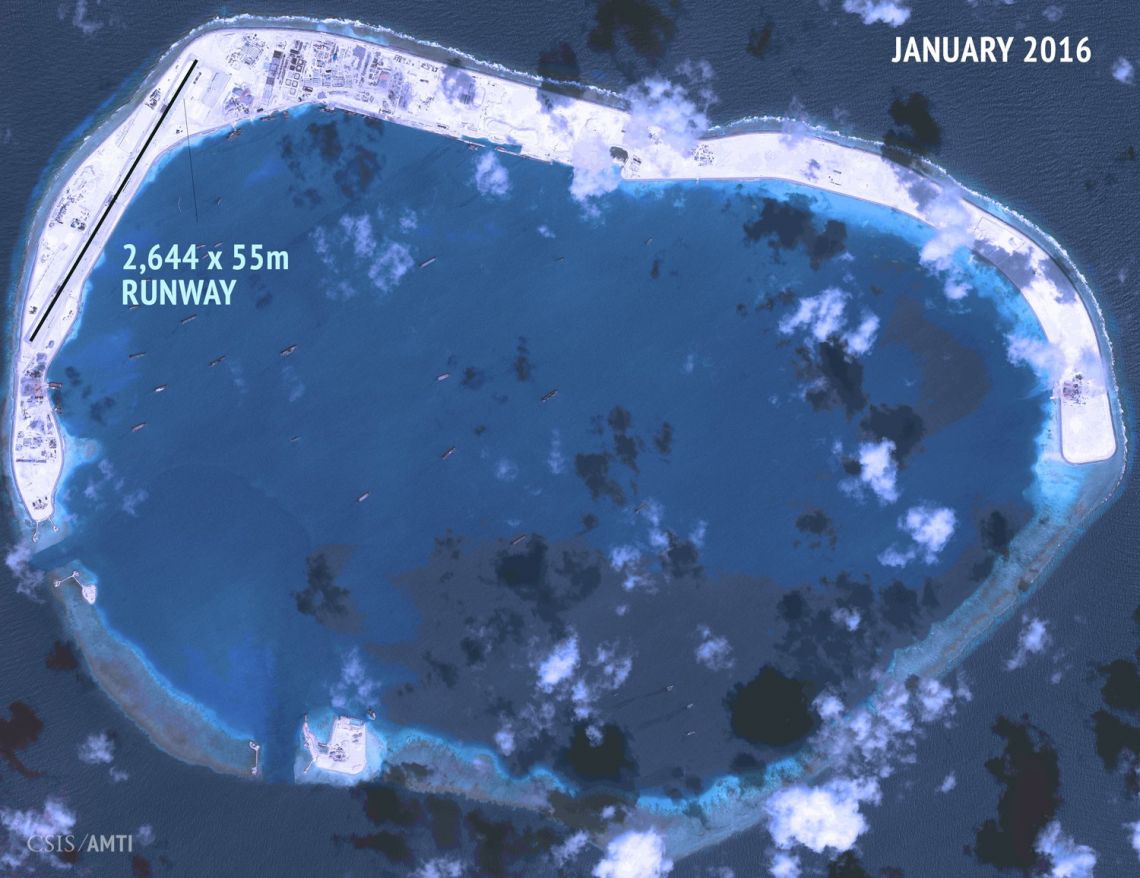

In 1995, the Philippines discovered that China had built structures in Mischief Reef (Panganiban Reef to Filipinos and Meiji Jiao to the Chinese), 150 miles west of Palawan and 620 miles southeast of China. Recent photos showed the reef has been upgraded into what looks like a military facility with its own an airstrip.

Mischief Reef is just 21 nautical miles from Second Thomas Shoal (Ayungin Shoal to Filipinos and Ren ai Jiao to the Chinese) where the Philippines has deliberately grounded BRP Sierra Madre, a dilapidated U.S. built-landing ship manned by nine members of the Philippine Marines.

China’s occupation of Mischief Reef, which the Philippines vigorously protested, underscored the need for a Code of Conduct in the South China Sea. The discussions led to the 2002 DOC.

In the last three years, China has converted the seven rocks and reefs it occupies into islands, through reclamation, fortifying them with what Western military analysts say are military installations.

Incidents of fishermen of one country venturing into claimed territorial waters of another, and being arrested, are common in the SCS. But one such incident led to a bigger conflict.

The arrest of Chinese fishermen in Scarborough shoal (Panatag or Bajo de Masinloc to Filipinos and Huangyan to the Chinese), 124 nautical miles off the shores of Zambales province in northwestern Philippines, on April 10, 2012 led to a two-month standoff which prompted the Philippines to file a suit before the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague. The Arbitral Tribunal’s eventual decision favored the Philippine position on maritime issues nullifying China’s all-encompassing 9-dash line claim over the South China Sea.

Last year, senior officials of ASEAN and China agreed to speed up consultations on an implementable Code of Conduct (COC) and work towards the finalization of a framework by middle of this year. The talks take place from Feb. 29 to March 2 during the ASEAN-China Working Group meeting in Boracay Island.

The framework is hoped to be the most significant achievement during the Philippines’ chairmanship and hosting of the 50th year of ASEAN.

Philippines ASEAN Affairs Assistant Secretary Hellen Dela Vega underlined a disconnect between ASEAN and China on the issue of self-restraint alone.

“Why do we keep saying full and effective implementation of the DOC? Because there are important paragraphs in the DOC where there is a disconnect between ASEAN and China, and Paragraph 5 is where we want China to fully cooperate with us,” de la Vega said in a recent forum on Maritime Challenges in the Asia Pacific in Manila.

“But China said, let us not talk about self-restraint, let’s talk about cooperation,” she added.

The disconnect is manifested in the difficulty of ASEAN and CHINA to come up with a COC, settling for a framework 15 years after they declared their intention for a Code.

Mischief Reef. Photo by Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative.

ASEAN’s role is also put to a test in negotiating this framework with China, which insists on dealing with ASEAN countries individually as 10 member states rather than collectively.

The member states of ASEAN are Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. Four of them—Brunei, Malaysia, Philippines, and Vietnam—are claiming parts of SCS, while China and Taiwan are claiming almost the whole of it.

“When China deals with ASEAN on the DOC, it wants (to do so) not as ASEAN and China but as individual member states of ASEAN and China, so we are 11,” de la Vega said. “They want to refer to it as an 11-party process and not as an ASEAN-China process meaning that the 10-ASEAN member states and China within the DOC and COC process.”

De la Vega said such as approach “uses the collective strength of ASEAN as a block and undermines its very existence as a regional grouping.” Manalo said the Philippines as chair will insist on using the same approach it employed in reaching the DOC in 2002.

“It will not be done individually otherwise it wouldn’t be an ASEAN-China code. That would be the approach we will be taking just like the principles of the DOC, that’s all the ASEAN countries and China. But this is basically just a framework, it’s not the code. I think we will just have to see how things develop but we are hopeful,” Manalo said in an interview by VERA Files for Reporting ASEAN.

In negotiating the framework for the COC, the Philippines has already stated that it will not raise the issue of the UN-backed Arbitral Tribunal decision.

“For our purposes, with respect to the Arbitral Tribunal, we feel no special benefit to raise this,” Philippine Foreign Affairs Secretary Perfecto Yasay Jr. said in a press conference on Jan. 11. “This is a matter that we will be raising with China at some future time on bilateral talks and to do so and involve others in the discussion of this decision is just simply counterproductive for our purposes.”

Dr. Tang Siew Mun, head of the ASEAN Studies Center at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) in Singapore, sees merit in that position, warning that any reference to the decision in a statement is a red line the Philippines should not cross.

“I think we should steer clear from this red line. I don’t think we should poke China in the eye…we can engage China in different ways. We need not mention the Arbitral ruling because the Philippines said this is a bilateral issue. We were very lucky that none of the nine other ASEAN countries crossed that red line,” Tang said in a recent interview in Singapore.

But he also said ASEAN as a whole should not water down the basic foundation lines of ASEAN that define the core responses to the SCS issue – respect for the rule of law, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), diplomatic and legal processes. “This is not offensive to China. After all it is a signatory of the UNCLOS,” he said.

(This story was produced under the Reporting ASEAN Program and media series implemented by Probe Media Foundation Inc., supported by an ASEAN-Canada project, funded by the Government of Canada. It is also in partnership with Air Asia, which is supporting the travel of journalists and other participants, and in collaboration with the ASEAN Foundation.)