BANGKOK (Reporting ASEAN) – Intra-ASEAN migration will continue to thrive as economic integration deepens, but it badly needs a dose of effective approaches to make it produce even better benefits for both the economies and societies in this region of more than 640 million people, according to a just-released World Bank report.

Called “Migrating to Opportunity: Overcoming Barriers to Labor Mobility in Southeast Asia,” the report says that ASEAN, which turns 50 this year, is missing out on achieving real economic integration if it does not recognize and allow more labor mobility – including for unskilled ones that make up the most of its migrants.

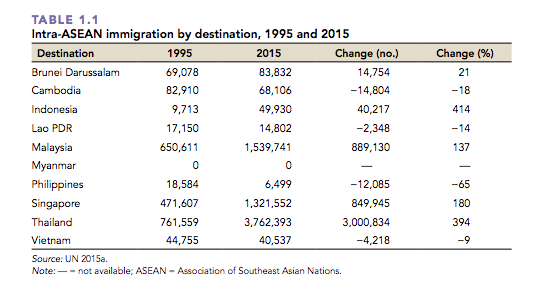

Migration among the 10 ASEAN member countries has risen over the two decades since 1995, so that there are now 6.89 million intra-regional migrants in the region.

Table lifted from “Migrating to Opportunity: Overcoming Barriers to Labor Mobility in Southeast Asia.”

Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand host 6.5 million migrants, or 96 percent of migrants in ASEAN, most of them low-skilled and undocumented ones working in the construction, plantation and domestic services. Thailand has the most number of migrants at 3.7 million as of 2015, mostly from Myanmar (53%), Lao PDR (26%) and Cambodia (21%).

“We would expect the migration flows to increase over the next years as a result of more economic integration,” Mauro Testaverde, the lead author of the 310-page report, said at a media briefing launching the report in Singapore.

Indonesia, Myanmar and Malaysia send the most migrants to other ASEAN countries, with Myanmar having sent out 2.2 million migrants.

The ASEAN Community aims to make ASEAN “a single market and production base characterized by free flow of goods, services, and investments, as well as freer flow of capital and skills”. The freer flow of skills covers a limited number of professions, through Mutual Recognition Agreements (MRAs) that ASEAN states have not been prompt in putting in place.

“These movements of people are a consequence of the region’s rapid economic growth and its diversity as a well as a contributor to its continued vitality,” said Sudhir Shetty, chief economist for East Asia and the Pacific and Michal Rutkowski, senior director for social protection and jobs global practice at the World Bank, in the report’s foreword.

The report talks about the positive contributions that intra-regional migration has brought to the ASEAN region, pointing out that it is in fact often under-utilized and under-appreciated on one hand, and over-blamed in the matter of undercutting wages, employment rates, or brain drain, on the other.

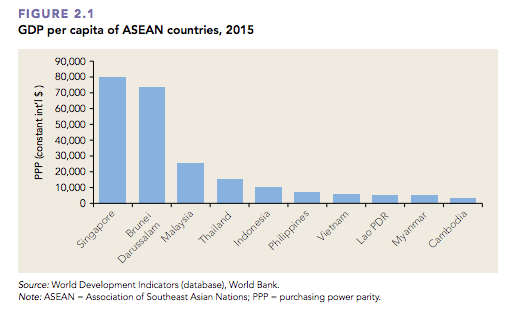

Migration in ASEAN has thrived due to factors that create push and pull forces for migrants. These include the wealth and income disparities given that the richest ASEAN country is 25 times wealthier than the poorest, large gaps in the age of its populations, and emerging labour shortages.

“In all but one of ASEAN’s 10 largest migration corridors, the GDP per capita of the destination country is at least twice that of the origin country,” the report found.

In sum, “the mismatch in the supply and demand of labor will encourage people of working age to seek employment in different parts of the region,” Shetty and Rutworksi said.

But while the drivers of migration will stay and are crucial to ASEAN’s dynamics, the recognition of the place of unskilled labor and the setting of political and political mechanisms to better manage their movement are found nowhere in the ASEAN Community plans.

It is a blind spot in ASEAN’s vision, which has chosen to free up the movement of capital and investments while glossing over the issue of migrant labor in its midst. Many ASEAN states prefer to deal with labor migration bilaterally, finding the issue too sensitive for domestic constituencies. Many destination countries see the economic benefit they get, but are much less willing to afford social and rights protection to foreign migrant workers.

“The way to think about migration in this region, in ASEAN, is that it’s very much a complement to the economic integration that is envisioned and that one hears a lot about at the trade front, which really is at the center of the ASEAN Economic Community,” Shetty pointed out in the briefing. “One point this report tries to make is that ASEAN also needs to think of labour as part of that movement toward an integrated region – because whether political leaders like it or not, migration is a reality.”

“The report tries to highlight this, not just in terms of the economies of the region, but the welfare of those who are migrating across borders,” Shetty said, stressing that effective policies are those that benefit not only sending or receiving economies but improve the quality of life of migrants themselves.

Since 1995, ASEAN member states have been taking steps to reduce barriers to labor mobility among skilled professionals. By 2025, the AEC Blueprint 2025 sees the reduction and standardization of documentation requirements and the completion of arrangements for the mutual recognition of professional qualifications.

“However, progress on implementing regional commitments related to labor mobility has been limited,” the report said. MRAs are “narrow in scope” and cover only doctors, dentists, nurses, engineers, architects, accountants and tourism professionals who account for just 5% of employment in ASEAN countries. “Relatively onerous qualification and verification processes remain in place, even for the covered professions,” it said.

“Finally and most important, each state’s migration procedures remain paramount, meaning that the decision regarding how many and what type of work visas to grant and whether to accept or reject an application for a visa continues to rest with individual ASEAN member countries,” the World Bank report pointed out.

Thai law bans migrants from working in 39 occupations that include engineering, accounting and architecture – which are covered by the MRAs.

The report added: “The AEC’s focus on high-skilled migration ignores the majority of AESAN migrants, who are low-skilled and often documented. The AEC does not have plans to facilitate the migration of low-or mid-skilled migrants, although some regional dialogue has taken place.”

In 2007, ASEAN issued a declaration on the protection and promotion of the rights of migrant workers, including undocumented ones. The Philippines, current ASEAN chair and the world’s largest exporter of human labor, pledged to push for a legally binding code for migrant workers this year, but reports indicate that ASEAN leaders will issue a document indicating “consensus” – not legal commitment – at the upcoming November summit.

Its failure to address migration challenges is making ASEAN miss out on one of its strongest economic and development assets – its migrants, argues the report.

Region-wide, worker welfare would be 14% higher if barriers to the movement of labour were reduced, it said. “Worker welfare would improve even more across ASEAN countries if barriers to mobility were lower for all workers.”

The report looked into worker welfare in these areas – the “generally small” impact of migration on employment rates and wages in destination countries, the higher wages that outmigration can bring to non-migrating workers, and the much higher wages migrants can get by moving across borders.

“Singapore’s average monthly wage of US$3,694 in 2013 is more than 30 times that of Cambodia. Malaysia’s average monthly wage is triple that of Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam,” the report noted.

Table lifted from “Migrating to Opportunity: Overcoming Barriers to Labor Mobility in Southeast Asia.”

Remittances from migrant labor reached 62 billion dollars in 2015, making up 10% of GDP in the Philippines, 7% in Vietnam, 5% in Myanmar and 3 % in Cambodia, with potential for reducing poverty in sending countries.

“Most evidence from ASEAN suggests that immigration has a positive impact on economic growth,” the report said. In Thailand, it said, the country’s GDP would fall .075 percent without migrants in it workforce.

The report encourages ASEAN states to reduce the cost of labor mobility, respect migrants’ rights and social protection, pursue better governance through legal and institutional frameworks, improve the admissions, employment, exit and enforcement component of migration systems, step up coordination between sending and receiving countries, and better manage employers and recruitment agencies.

For instance, workers entering Malaysia in the 2000s faced labor mobility costs up to thrice the annual average wage. In contrast, those migrating to Myanmar and Vietnam faced costs equal to more than 11 times the annual average wage.

“In Thailand, labor brokage fees are hundreds of dollars higher for migrants from Cambodia and Lao PDR who choose to migrate formally than those who do so informally,” the report quoted a study as saying.

“Both sending and receiving countries tend to focus on the short-term benefits and costs of migration” in their policies, “ it added.

While the Jakarta-based ASEAN Secretariat has political constraints, the report suggested it could be a “clearinghouse for best practices and a coordinating body”, collecting bilateral agreements and memoranda of understanding from ASEAN and other regions.

“It might consider developing a common, but flexible, framework for bilateral agreements, guidelines for the protection of migrant workers, and even model contacts”. ASEAN could also create a “labor market informal portal” that can give potential migrants with information about job openings, employment regulations and practices in destination countries, it added.