By JAKE SORIANO

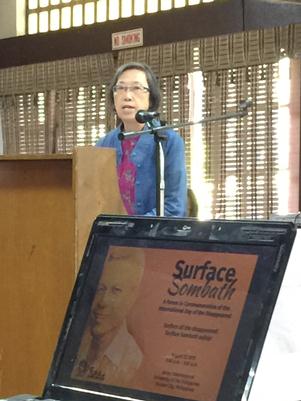

SOMBATH Somphone is easily recognized because of his white hair. The white is clearly visible in the grainy CCTV footage that recorded the last time he was seen alive.

More than the said physical attribute, Sombath is a distinguished man, not just in his native country Laos. A civil society leader who has worked to uplift the lives of Lao farmers, he received in 2005 the Ramon Magsaysay Award, dubbed Asia’s version of the Nobel Prize, for his efforts to promote sustainable development.

Ng Shui Meng said she came to the Philippines with Sombath, her husband, when he received the award ten years ago.

“It was a happy time,” she recounted, before correcting herself, “It was, in fact, a jubilant time.”

“I’m here again ten years later, but under very different circumstances,” she told those present in a gathering last week at the University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman. “Sombath is not with me. Sombath was disappeared.”

Showing screen grabs of the CCTV footage, Ng detailed the evening of December 15, 2012, when her husband was stopped and picked up by the police in the Lao capital Vientiane, and was never seen again.

“To this day, three years later after Sombath’s abduction, I’m still at a loss,” she said.

That such fate could befall a prominent civil society leader should be a grave concern for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), said advocates from across the region who attended the event, days ahead of the August 30 International Day of the Disappeared.

It would be “hypocritical” of ASEAN to have singular democratic aspirations if its member governments fail to act on enforced disappearances, said Walden Bello, former Akbayan party list representative, in a keynote message.

“You cannot have an ASEAN made up of governments that tolerate such human rights violations,” said Bello, who along with a team of ASEAN parliamentary representatives, visited Laos in early 2013 to investigate the disappearance of Sombath.

“It would be hypocritical to say that we are united in democracy, that we are becoming one as a democratic region, when we have all these abuses of human rights that continue to take place,” Bello added.

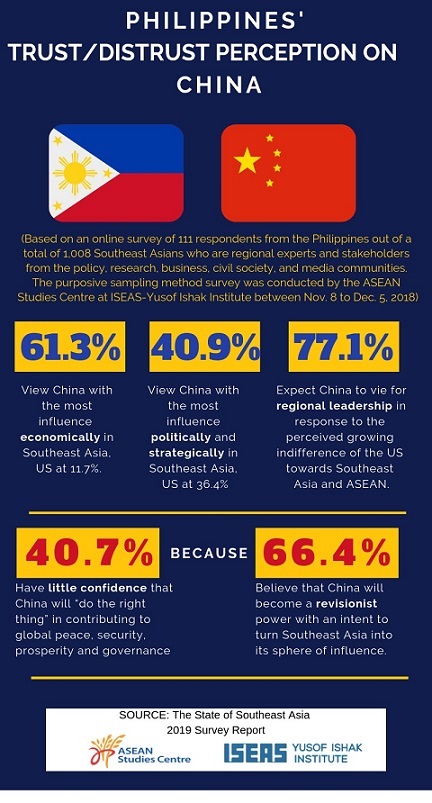

Figures from the Asian Federation Against Involuntary Disappearances (AFAD) show that some 800 cases of enforced disappearances in ASEAN member countries have been filed before the United Nations.

The Philippines has the most cases filed at 625; followed by Indonesia, 163; Thailand, 71; Laos and Myanmar, with two each; and Cambodia, one.

“The figures represent the tip of the iceberg vis-a-vis the actual number of cases, since families and witnesses are fearful of reprisals from state authorities,” said AFAD in a statement.

Among ASEAN member countries, Indonesia, Thailand and Laos have signed the UN Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance. Only Cambodia however has ratified it.

The Philippines in 2012 enacted Republic Act No. 10353, the first domestic law in Asia defining and penalizing enforced disappearances. It has yet to sign or ratify the convention, which said AFAD, could have complemented its existing domestic law.

Ng said she personally hopes that the Philippine government, which already has the national law, ratify the convention and be a model for ASEAN and the rest of Asia.

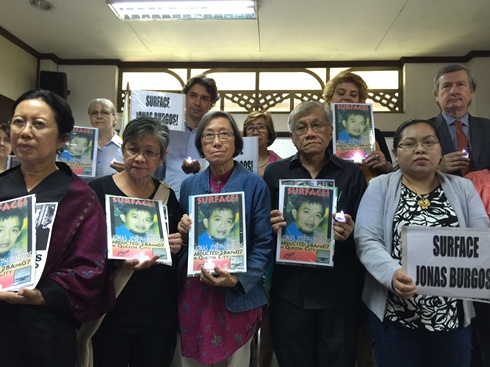

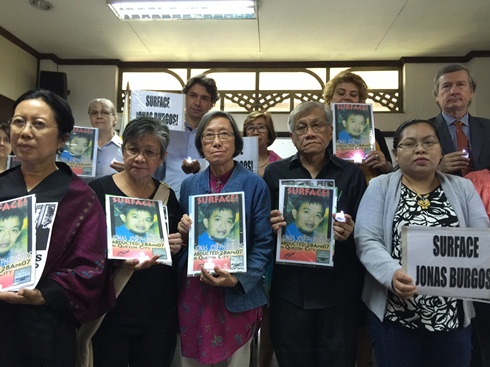

Edita Burgos, whose son Jonas Burgos was disappeared eight years ago, said that she considers Sombath and her son “brothers.”

“They served in circumstances that were not easy,” she said.

Jonas, a farmer activist and son of renowned publisher Joe Burgos, was abducted inside a Quezon City mall on April 28, 2007. He remains missing until today.

The Court of Appeals has ruled that his case was one of enforced disappearance, with the Philippine Army responsible.

In a solemn speech, Edita Burgos urged to “spread the message of peace, love and forgiveness founded on justice.”

“We shall not allow the perpetrators to be our teachers,” she said. “We shall not be cruel ourselves. We shall show them that we say no to violence.”

UP Diliman Chancellor Michael Tan reminded of the disappearance of Karen Empeño and Sherlyn Cadapan, students of the university who were seized by gunmen in Bulacan on June 26, 2006, and never seen since.

The man charged behind the kidnapping, retired Army general Jovito Palparan, was arrested in 2014 after years in hiding, and is facing trial. The fates of both Empeño and Cadapan still remain unknown.

Two Ramon Magsaysay Award recipients present in the event expressed their solidarity to all families of the disappeared, and also urged strong action on the issue.

“Let us not be intimidated by state repression,” said Lahpai Seng Raw, who received the award in 2013 for her peace and development efforts in Myanmar.

“We must not let Sombath and other victims disappear from the face of the earth, forgotten, as if they never existed.” she said.

Jon Ungphakorn, who received the award for his work on HIV-AIDS in Thailand the same year as Sombath did, noted that enforced disappearances are an ASEAN, and more broadly, an international concern.

“It is a crime against humanity,” Ungphakorn said. “It is never just a domestic affair of one country.”

He said it is the obligation of the ASEAN human rights commission to be at the forefront of all cases of enforced disappearances.

“Enforced disappearance is in my view one of the most cruel and violent crimes that can be committed against a human being,” he said.

“And it is not just committed against that human being, but his or her family, and his or her community, and the whole society.”