(Seventy years ago, on Sept. 2, 1945 Japanese delegation led by Japanese foreign affairs minister Mamoru Shigemitsu signed the instrument of surrender about the American battleship USS Missouri ending the six year war that killed an estimated 60 million. The survivors had to live with the trauma of war.

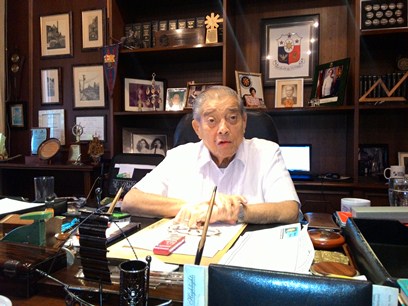

(Businessman and former ambassador to Spain Juan Jose Rocha recalls the horrors of war he witnessed as a child.

(The interview was done a month before he passed away last July.)

By Johnna Villaviray Giolagon

Former Ambassador to Spain Juan Jose Rocha was seven and a half years old in 1945 when the Americans came to liberate the city of Manila from Japanese occupation.

He was with in the family house just across the Malate Church when the Battle for Manila had begun.

“We were hoping it would be as peaceful as it was when the Japanese came in, that Manila had been declared an open city. But that never happened.”

What happened was that Manila burned.

On 11 February 1945, a group of 24 family members and helpers were holed up in the Rocha residence. The eldest was his 70-year old grandmother while the youngest was a two-week old cousin.

“We had a call from another friend, relative, who was living near Santo Tomas University, which was the internment camp for the third nationals or the Allied civilians – Americans, British, Australians, Canadians. Rumors were out that they were digging trenches or something in Santo Tomas.”

“About half an hour later, this relative called back and said no, the Americans have liberated Santo Tomas. The shooting was the fighting with the Japanese guards. So we were very happy, that tomorrow they would come here across the Pasig.”

But the adults knew the Japanese would not give Manila up without a fight. So they slaughtered ducks and prepared adobo to last several days. The children carried identification papers in their backpacks should they be separated from the adults.

On 12 February, the shelling got closer.

“We heard these heavy explosions. They were blowing up the bridges…all the bridges in the Pasig were blown up. And we started to see that there was fire far away. This was in the commercial district – Escolta, Santa Cruz. You could hear the explosions.”

The Americans were unable to cross Nagtahan Bridge until four days later. In those four days, the young Rocha and his family had to endure daily shelling from both the Japanese and American sides. Rocha also saw houses and their owners go up in flames. The gate leading to the street had been locked so the people could not run out.

“The city was burning, it was hot. At night it was all orange from intentional fires.”

His family escaped by cutting the barbwire the Japanese knotted around their fence. They moved to another house that offered better protection from the shelling. It was from there that Rocha saw his childhood home go up in flames. It was also there where he felt American artillery fall too close to them.

One of those shells hit his mother in the head on 13 February. The adults dug a shallow grave between two galvanized sheets where her remains stayed until a proper burial could be made after the war.

A neighbor was also killed and two helpers were wounded in the shelling.

“(A) young girl had her whole back was fell off. They just put alcohol – rum – and some powdered pills – sulfa or something – and then put the skin back on and then they put a sheet and tied it around her. That was all. She was screaming.”

In another incident, Rocha witnessed a woman trying to cross the street when she was hit.

“They had to cut her arm off, amputate her arm. She was awake. There was no anesthesia. This doctor – a family doctor – did not have his box anymore. He had lost it. He had amputated her using a biology kit – a biology kit when I was a kid was used to cut a frog – and they amputated her arm.”

“She was screaming and crying. First they gave her a lot of brandy I think, tried to get her drunk. They amputated her arm right next to me, right next to me. I was watching this. And afterwards she died.”

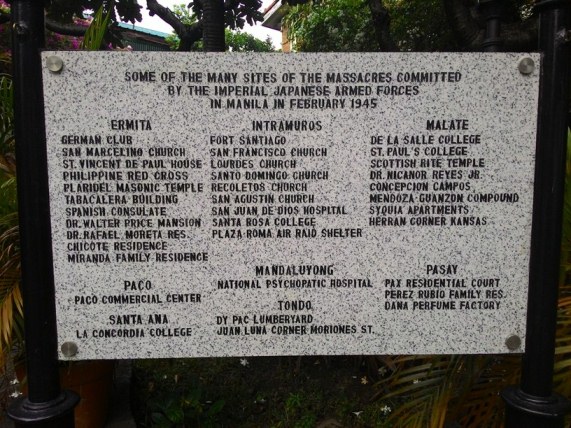

Later, Rocha learned that 13 other relatives were killed at the German Club in Intramuros.

“I had a grandaunt, four aunts, and eight cousins there – all boys aged 18 months to 12 years or 11 years. They were all killed. The younger children, 2 of them were thrown (in the air) and caught with bayonet.”

“One of my younger aunts who was single was raped, what we call in English gang raped…on the driveway of the clubhouse. And when they finished the rape, they cut her open in the stomach and left her to die there in the sun. Luckily a shell fell and killed her.”

The rest were burned alive as the Japanese set the cement building on fire.

That night the Rochas transferred to the house across the street that offered better protection from the shelling. They crossed in batches so they wouldn’t catch the attention of sentries ordered to shoot at anything that moved.

They slept in the stable that night.

On the following morning, the 14th of February, a group of at most eight Japanese soldiers accompanied by Makapili interpreters came.

“This officer came and he said go away, this place no good because there’s going to be plenty boom here…The Japanese said you go out, go to hospital.”

“The Japanese lieutenant took out from his shirt a medal and he said: Me Christian.”

“He saved our life.”

It was Valentine’s Day of 1945.

“Everything was burned, everything was destroyed, but there was no more machine gun nests so we were able to get to this Remedios Hospital, which was behind Malate Church. That was horrible. There were bodies all over in the floor – dead, wounded.”

“In the operating room there was a leg over the lamp. On the pathway there was a young boy who was covered with dry blood. The only way we knew he was alive was because when a fly would come in his eye, he would move his eye.”

They didn’t stay but transferred again across the street to the Malate school playground.

“We went to the far corner. We saw there were fresh graves on the floor – people had died there, buried them there. We saw bullet marks on the wall and we were told that the night before they had massacred civilians there.”

That night, the group built a makeshift shelter from galvanized sheets and a mattress in a driveway of an abandoned house. The property had a deep well so now they finally had a source of water.

“We were very thirsty. No water for three days and we were very thirsty. So they decided we had to get some water (and) there was a well in this house (but) they went there, there was a dead body inside the well.”

“Still they went, they put the bucket down (and) they pulled out the water, which was mostly mud, dirty. They put on this like a big frying pan and they let the mud settle to the bottom so on top was a little water. Then they threw iodine to disinfect.”

“We would drink with a teaspoon, taking turns. First the children then the adults, the help, taking turns until it was finished. And again, the same thing. That was how desperate we were.”

The morning of 15 February came with good news. The Americans have finally recovered San Andres. They followed a line of people walking that led them to a makeshift clinic that a Filipino doctor manned.

“He was all full of blood because he was all helping, cutting people, operating, sewing up wounds. He said any medical supplies you may have, please put them here on the table…all of a sudden, this guy runs up to the table and grabs an armload of the medicine and runs off.”

“The black market for medicine was very, very high before the liberation. The doctor just got his pistol and shot (the man). He shot (the man) and he continued (what he was doing). And we were not disturbed. We saw so much horrible things.”

The Rochas settled that night in an orphanage near the Paco train station. They occupied the third floor where bodies had been laid out on beds. They moved the bodies underneath and took the spot.

The following day, on the 16 February, an employee of Rocha’s businessman father Don Antonio Rocha came and offered a place for them to stay in Santa Ana district before they moved to live with relatives in Intramuros.

Later, Rocha was shipped to San Francisco. He returned to Manila in 1947 when the schools were ready to open.

Rocha acknowledged that he was very angry at the Japanese when he was younger but had gotten over it when, in a stopover in Yokohama on the way back to Manila, he saw the devastation the war brought on the Japanese as well.

Rocha passed away on July 20 this year, two weeks shy of his 78th birthday.