By JAN MARCEL RAGAZA and ALLIAGE MORALES

IF a minimum wage earner were to be stricken with diarrhea, relief can come cheap from the Department of Health’s Botika ng Barangay (BnB) outlets, where a 2-milligram capsule of generic loperamide would cost only P1.05.

The BnB price is vastly lower than what loperamide costs in commercial drugstores—P4.10 for generic and P14 for branded.

Launched by President Gloria Arroyo in 2001, the BnB program is the answer to poor Filipinos’ need for cheap medicine. But here’s the catch: There is not a single BnB outlet in some of the country’s poorest provinces and towns where they are needed most.

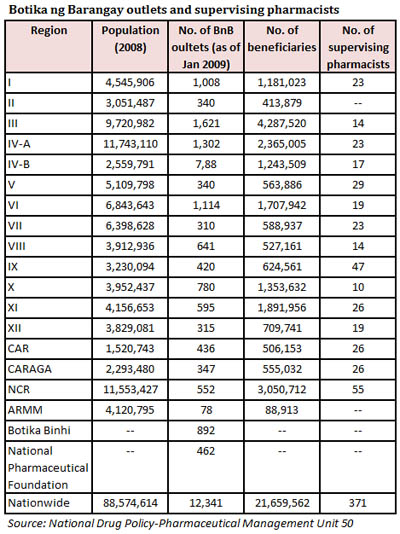

As of January 2009, there were 12,341 botikas, a long way from the 427 in 2003. But the program covers only half of the country’s 42,000 barangays and suffers from poor implementation and conflicting priorities from top to bottom. As a result, the BnB program has wasted scarce resources while denying health care services to the poorest areas it was meant to serve.

One example is the Autonomous Region for Muslim Mindanao which, aside from having the least number of hospitals and barangay health centers, has the smallest number of BnB outlets, numbering 78 as of last January. All the BnB outlets in ARMM are in Maguindanao, leaving the provinces of Basilan, Sulu, Lanao del Sur and Tawi-tawi without any BnB drugstore.

This is certainly a far cry from what Arroyo boasted at the inauguration of the 11,000th BnB in Camp Bagong Diwa, Taguig on April 11, 2008: “Kalat sa buong Pilipinas ang BnB…Ang masa ang pangunahing nakikinabang dito sa mas murang gamot na ipinagbibili (The BnB program is scattered throughout the country. The poor are main beneficiaries of the cheap drugs being sold).”

In fact, data released by the DOH’s Pharmaceutical Management Unit (PMU) 50 a month later revealed that the then seven-year-old BnB program had not reached Lanao del Sur, Tawi-tawi, Compostela Valley, Siquijor, Batanes, Marinduque and Sulu, which are among the country’s poorest provinces.

In fact, data released by the DOH’s Pharmaceutical Management Unit (PMU) 50 a month later revealed that the then seven-year-old BnB program had not reached Lanao del Sur, Tawi-tawi, Compostela Valley, Siquijor, Batanes, Marinduque and Sulu, which are among the country’s poorest provinces.

The 2007 BnB list also left out 15 out of the top 40 poorest towns in the country.

The country’s fourth poorest town is Tangkal, Lanao del Norte, where 86 percent of the population lives below the poverty line, according to the 2003 data—the latest—from the National Statistical and Coordination Board.

A midwife mans the town’s solitary health station. A doctor visits only thrice a week due to travel difficulties. Villagers travel to neighboring Kolambugan town for hospitalization and other health services, as the health center is in need of repair. Both Tangkal and Kolambuham do not have BnB drugstores offering cheap remedies.

This situation “runs counter to the goal of improving equity with regard accessibility,” said former Health Secretary Carmencita Reodica, who headed the first BnB prototype during the 1980s and made it her priority project when she became health secretary in 1996.

The program, added former DOH secretary Jaime Galvez Tan, “falls below expectations (because) it’s not really reaching the poorest.” The problem, he said, is that “health interventions gravitate (to) where it is easiest to be implemented…Alam naman ng gobyerno ‘yan (The government knows the problem with access to drugs).”

But the DOH Central Office does not have a direct hand in setting up BnB outlets, said Health Undersecretary Alexander Padilla and project executive officer of PMU 50. If there are no BnB stores in the poorest places, he said, it is the DOH’s regional centers for health development (CHDs) or community organizations and local government units that are responsible since BnB outlets are set up on their initiative.

A barangay has to have a population of at least 15,000 plus local government and community support before such a BnB can be set up there, said BnB coordinator in Central Luzon Marilu Malamug. The DOH then offers seed capital in the form of P25,000 worth of medicines.

By next year, when Arroyo leaves office, the DOH aims to establish 15,000 BnB outlets to benefit close to 21 million Filipinos. Padilla said the DOH is “right on track” since it has only 3,000 more to go to reach the target.

But equity in health can never be achieved if only a quarter of the country’s 80 million population will benefit from the program, said Marlene Bermejo of the Health Action Information Network (HAIN), a private organization conducting research on government health programs and services.

“Despite all of these efforts, there are only 18,000 barangays with botikas,” said Tan, referring to the BnB and the Botika ng Bayan, which is solely managed by the Philippine International Trading Corp. PITC is the mother company of the PITC Pharma Inc., which procures drugs for the BnB program.

Not enough drugs

But even in communities with BnBs, residents cannot turn to these drugstores for help for serious illnesses such as malaria, influenza and tuberculosis, the leading causes of mortality and morbidity in the country. The BnB also does not have medicines for filariasis and schistosomiasis, two of the leading diseases in some poor communities in the Philippines.

Medicines sold in BnB drugstores consist mostly of over-the-counter (OTC) drugs for minor illnesses such as diarrhea, dehydration, stomach acidity, coughs and dizziness. When the program started in 2001, only two prescription drugs for bacterial infections were dispensed—cotrimaxole and amoxicillin.

It was only in 2005 when five prescribed drugs for three of the leading mortality diseases were included in the BnB inventory: metformin and glibenclamide for diabetes, metropolol and captropil for diseases of the heart, and salbutamol for respiratory ailments.

“We do not [address] malaria, tuberculosis and AIDS in the BnB. We can only use so much resources,” Padilla said. He added that the DOH refuses to allow BnB outlets to carry medications for tuberculosis, currently the sixth leading cause of death in the country, because “we don’t want people to start curing themselves.”

Filipinos in need of medication for these diseases have to turn to private retailers, which offer a variety of more expensive, branded medicines they badly need, said Bermejo.

A regional BnB coordinator, who requested anonymity, disclosed that some operators who procure their own stock sell some prescription drugs strictly prohibited by the DOH.

In 2006, the Commission on Audit discovered that several BnB outlets in Caraga and Metro Manila sold unauthorized medicines. Caraga operators disclosed that they were buying Alaxan and Ambroxol, among others, because these were demanded by patients who suffer from bronchitis, the leading disease in the region.

Former DOH secretaries Reodica, Tan and Manuel Dayrit admit that under their administrations, the BnB outlets did not really address many diseases. “Yes, these problems existed in the past and continue to exist today,” said Dayrit, who headed the program in its early years in 2001 until 2005.

Tan had studied the type of medications available at community drugstores in his book Health in the Hands of the People. Referring to the BnB’s predecessor, the Marcos-era Botika sa Barangay (BsB), Tan wrote, “[They] sold anti-diarrheal drugs instead of promoting rehydration therapy or herbal medicines.” Tan advocates tailor-fitting a BnB’s inventory to the diseases in a community where there are no doctors.

In the town of Pakil, Laguna, BnB outlets usually experienced stock shortages because the medicine supply does not match the demand of the community, according to a 2007 University of the Philippines Public Health study. Cotrimoxazole and amoxicillin, two main antibiotics needed in the town, were usually unavailable at the 11 outlets studied.

Pakil is not an isolated case. State auditors recorded that more than P1.5 million worth of BnB drugs had already expired between 2005 and 2007 nationwide due to procurement of “unsaleable” and the least requested drugs.

Reodica attributes the wastage of government resources to the weak logistics of the DOH regional units and the poor inventory and management of BnB operators. Alice Laguindanum, staff of the PMU 50, said it is not the DOH’s “problem” anymore once the drug packages are in the control of its regional units.

Lack of manpower

Part of the management problems in the BnB program is the lack of manpower. Only a supervising pharmacist is authorized to dispense prescription drugs in the BnB, according to a DOH administrative order issued n 2005. The Pharmacy Law, meanwhile, requires that a drugstore should have at least one pharmacist.

The World Health Organization said in 2004 that only one pharmacist looks after the medicinal needs of every 1,664 Filipinos. The ratio has most likely worsened, as more pharmacists are being lured by better pay and working conditions abroad, said Bermejo.

The nationwide ratio shows that 33 BnBs are assigned for every supervising pharmacist. In 2007, only 371 pharmacists or food and drug regulatory officers (FDROs) were supervising the 10,279 BnB outlets as well as other public and private drugstores. An independent monitoring done by HAIN in 2006, meanwhile, showed that each FDRO was assigned to regulate 212 public and private drugstores.

The shortage of pharmacists has hindered the establishment of BnB outlets in hard-to-reach areas like those in Region 12, which is composed of the Cotabato provinces, Cotabato City, General Santos City, Sarangani and Sultan Kudarat. “There are only few outlets [in remote locations] because pharmacists are not interested to supervise in far-flung areas,” says Lilia Milanes, the FDRO in Region 12.

During her term in the 1990s, Reodica looked for an alternative, setting up BnBs near district hospitals and placed them under the supervision of the district pharmacist. Without a pharmacist’s advice, consumers resort to self-medication, posing a threat to the rational use of drugs, she said.

Padilla said the lack of pharmacists is not really considered a “major” problem since BnBs sell mostly OTC drugs and only seven prescription drugs. “There are some functions that anyone can do, like dispensing a prescription drug,” he said.

But the COA said the manpower problem has resulted in the expiration of prescription drugs in some regions. In Soccksargen, the COA said in its 2007 report, “more than half of the five prescription drugs sold at BnBs expired due to the non-availability of a supervising pharmacist who has the sole authority to dispense them.”

While the Bureau of Food and Drugs has so far never encountered cases of drug poisoning from the purchase of BnB drugs, Bermejo could not be certain that all drugs in all BnB outlets are safe, especially since hundreds of outlets sell drugs even without a special license to operate (SLTO) from BFAD. Also, BFAD only has one testing center based in Muntinlupa City. This means all tests must be done in Metro Manila.

Padilla said the problems reported by the COA have been addressed. “Wala na kaming nakikita na mga nag-eexpire ngayon ha (We have not come across expired drugs these days). Kung meron man (If there are), not to the extent that huge government resources will be wasted,” he said.

It is now up to the LGUs to deal with the “minor” problems of the BnB like licensing and monitoring, Padilla added. He said the BnB program, in the first place, is meant to engage the LGUs in the delivery of health care service.

“We don’t operate it (as if with) a remote control,” explained Padilla. The DOH central office, he said, is only in charge of training the operators, while LGUs are the ones that can best assess the economic conditions of their area and the subsequent placement of BnB outlets.

Claiming that the program is disjointed from the overall delivery of health care service, Bermejo said: “Aside from its operational flaws, I feel that the framework in which the BnB is implemented is being overlooked.”

Health spending experienced a steep drop under the Arroyo administration, forcing Filipinos to spend more for badly needed health services. In 2008, the total national government health spending of P253 per Filipino was 27.5 percent less than what was spent in 1997. Between 2000 and 2004, government spending on health fell from 41 percent to 30 percent of total spending, while out-of-pocket spending increased from 41 percent to 47 percent.

Meanwhile, community health worker Eleanor Jara could not forget a BnB outlet she saw in one of the poor provinces of Mindanao. She was with two representatives of the European Union studying the health situation of barrios ravaged by the ongoing war.

The BnB they came upon only had a single, small cabinet less than a meter high, containing very few medicines. At the time, no one was manning the drugstore. Confounded by the sight of the BnB outlet, the EU representatives asked Jara, “What is this thing?”

“It’s Arroyo’s BnB program,” she said.

(The authors are senior journalism students of the University of the Philippines. This two-part report is an abridged version of their thesis, which was done under the supervision of UP journalism professor and VERA Files trustee Yvonne Chua.)