By CHERRY JOY VENILES

IN Florencio “Butch” Abad’s book, the national budget is a game—a game, he says, in which “political actors with conflicting demands and competing to get a larger pie of the nation’s scarce resources.”

But years of experience as politician, lawmaker, academic and Cabinet secretary in three government administrations have also shown him the huge potential of the budget: “It is also a very good point to start a reform process that will pursue an agenda of empowerment.”

And that was what he said he set out to do when he was made boss of the Department of Budget and Management in 2010.

The reforms he has since instituted under the DBM’s “Paggugol na Matuwid” program have not gone unnoticed. The Metrobank Foundation recently named him 2012’s Metrobank Professorial Chair for Public Service.

In a lecture to a packed audience of students, NGO leaders, teachers and representatives from the DBM at the awarding ceremony held March 7 at the Ateneo de Manila University, the Harvard-trained Abad explained his public expenditure framework: Spend prudently (“within our means”), spend effectively (“on the right priorities”) and spend efficiently (“with value for money”).

Put into action, the framework has resulted Abad’s centerpiece programs at the DBM: the zero-based budgeting (ZBB) process, performance-based incentives for government employees, increased budget for social services, and improving transparency through the use of technology.

Zero-based budgeting

Under ZBB, when a government agency submits its plans at the start of a budget cycle, it must assume it is starting from scratch.

The method requires analyzing and monitoring whether projects and programs and the amounts allocated to them are being properly used according to the approved plan. Any deviation could mean forfeiture of the funding.

In the last budget cycle—from budget preparation and legislation to implementation and accountability—budget analysts scrutinized the relevance of government programs and projects to determine if a government program should be continued, terminated or redesigned based on agency mandates, Abad said in his lecture.

In some cases, projects proven inefficient and ineffective were suspended and funds reallocated to where they are most needed or where they can create more impact, he said.

Abad denied allegations that President Aquino’s fight against corruption is driven by political vendetta. He said the administration has uncovered serious problems inherited from the Arroyo administration which led to the cancellation or suspension of projects funded by Official Development Assistance (ODA) loans.

The projects, the budget secretary said, include dredging of Laguna de Bay, extension of the North Rail Extension and construction of roll-on-roll-off ports which, after DBM’s assessment, were found wanting in economic viability.

Minister Akio Isomata of the Japanese Embassy in Manila’s economic section has said the implementation of ODA projects in the Philippines remains slow and the utilization and maintenance of aid-supported projects like major roads and ports low.

These, in turn, have become major concerns for Japanese investors who have complained of congested roads and ports and the expensive and unstable power supply in Mindanao, he said.

Japan has been a leading economic and development partner of the Philippines, with billions in total bilateral trade and investments.

Public servants for reform

In his 2012 State of the Nation Address, Aquino announced the implementation of a system for government employees in which bonuses are based on their agency’s ability to meet their annual targets.

Government workers’ incentives, the President had said, will depend on how well they have delivered outcomes aligned with the administration’s key outcome areas anchored on the government’s Social Contract with the Filipino People.

Out of the President’s directive to “put flesh and bone to democracy, to bring decency back into government so it is capable of nurturing its people” was born Abad’s performance-based bonus (PBB) system which has received mixed reactions from government employees.

From a good governance perspective, the PBB seems like a sound strategy to improve services across the bureaucracy, but many in government, particularly in big agencies such as the Department of Foreign Affairs and Department of Labor and Employment see the approach as divisive.

“How can regular encoding work be reconciled with the difficulties of handling assistance to nationals’ cases? One would be hard pressed to quantify the work involved in case building and counseling,” one DFA officer said.

Where before, civil servants are assured of productivity pay and Christmas bonuses sourced from the agency’s savings, now, through the PBB, employees ranked as “Best” in a best-performing bureau stand to receive as much as P35,000, while underperformers—those who were unable to meet at least 90 percent of their individual targets, or employees in a poorly ranked bureau—will not be eligible for PBB.

“Actually, this is how the books have always defined a healthy PEMS (Public Expenditure and Management System) but between the budget process, COA (Commission on Audit) auditing and the employees’ performance evaluation—you would have gone through more than a dozen reporting forms to complete a cycle,” said the division head of a government planning office based in Manila.

The preparation of a national budget takes the DBM all of six months. During this time, the various government departments and agencies submit budget proposals which are then reviewed and assessed by both DBM and Congress.

Once the budget is released, the agencies use the funds based on the plans submitted and subsequently prepare separate reports to DBM for reporting agency expenditures. Eventually, the COA conducts a separate review of the disbursement process at the end of each fiscal year.

In the current system, budget preparation forms are different from the auditing forms used by COA to probe and audit agencies—from the reporting and accounting forms used for submission to the DBM and the performance evaluation tools used by the Civil Service Commission to evaluate employee effectiveness.

As a result, implementation of the key reforms has been uneven across the bureaucracy.

Transparency seal and social service budget

With the “Paggugol na Matuwid” as budget philosophy, government agencies are now required to disclose their approved budgets and other budget information in their websites through the Philippine Transparency Seal. This allows the public to access government information often inaccessible in the past.

In turn, the transparency seal is one of the requirements before agencies are allowed to release their employees’ PBBs.

To improve transparency, efficiency and speed up the delivery of programs and projects, technological innovations in the procurement of government goods has also been strengthened through the Philippine Government Electronic Procurement System (PhilGeps).

This allows anyone interested in the mystery of the Philippine budget to know, for instance, how much money was given a town or city. One can verify if a certain barangay road project was ever built or a livelihood training program ever conducted.

This kind of transparency allows people to see exactly where their taxes go and for what purpose it has served.

In his lecture, Abad said, “The more transparent the government is with the budget, the more savings it can generate to address basic social service needs of its people.”

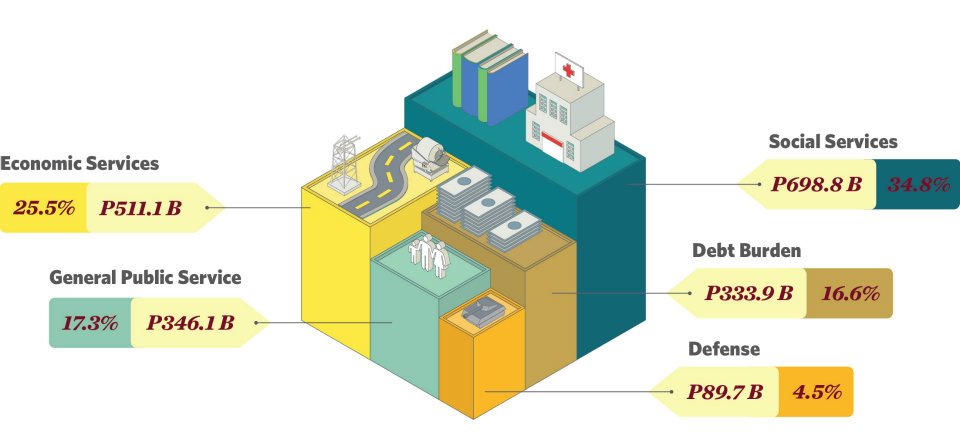

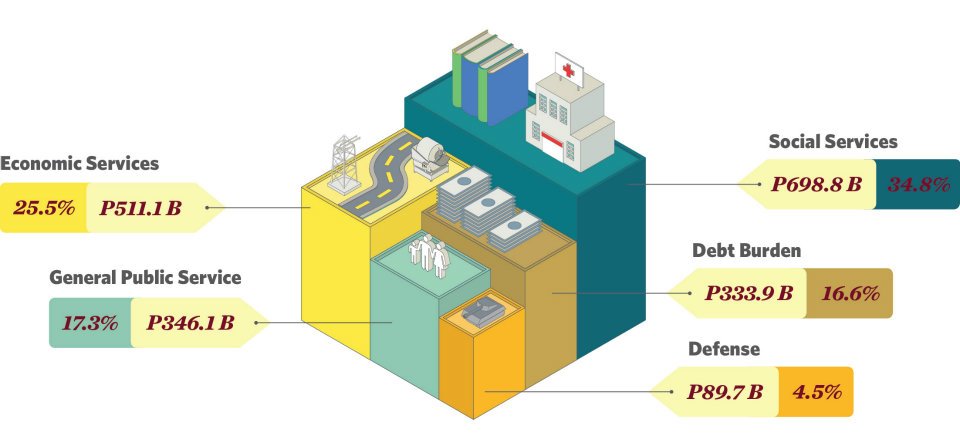

The budget secretary said these reforms have significantly increased the budget for Social Services—in absolute terms and as its share in the total budget pie—since 2010.

These, in turn, have resulted in unprecedented investments in poverty reduction programs and projects such as the expansion of the government’s conditional cash transfer program, addressing the shortage of teachers, classrooms and textbooks, and the implementation of the K-12 program which, Abad said, reflect the administration’s priorities.

In the 2012 National Budget, the Social Services sector got the largest slice of the budget pie with P568.6 billion or 31.3 percent of the total budget. This was followed by the Economic Services sector with P438.8 billion (24.2 percent), which showed the largest growth of 21.3 percent . Debt service came next with P356.1 billion (19.6 percent); General Public Services, P338.1 billion (18.6 percent); Defense, P114.4 billion (6.3 percent) and the remaining for debt payments.

Said Abad, “Good governance and the national budget matters because it will hopefully make us all more engaged, more empowered.”