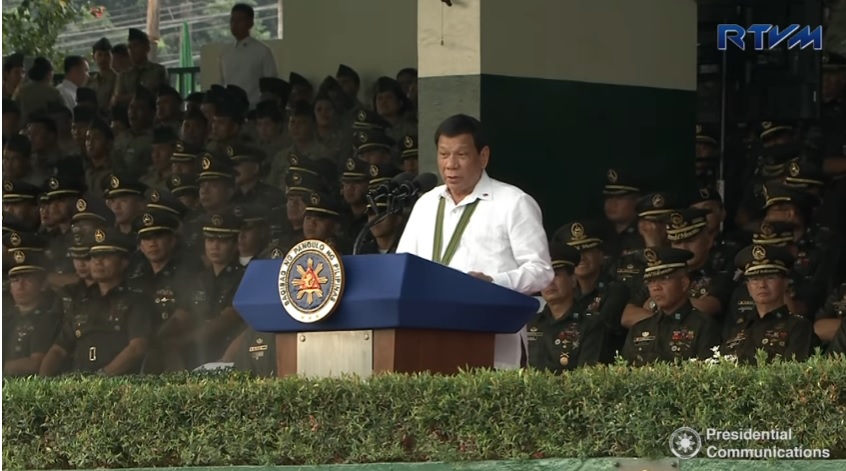

Pres. Duterte addressing the military. Screengraby from RTVM file photo.

It looks like another naive, impulsive move, but turning over the Bureau of Customs to the military is possibly the most dangerous move Duterte has hatched.

Before this, the military has refused to be involved in the war on drugs. It has refused Duterte’s invitation to spearhead a revolutionary government. He has chided the military for missing the chance to transform the country through extra-constitutional means. The military has backpedalled the Duterte order to void the amnesty to Trillanes, and incidentally, all similarly placed military officers. The military has continued to profess loyalty to the Constitution.

But Duterte apparently is on occasion a sophisticated schemer. He is sending the military to partake of the forbidden fruit — the Bureau of Customs. This bureau is the most corrosive government agency. This agency has the most efficient machine for the privatization of public resources, and making mafiosi of government officials. It is an aberration, where mere clerks can come to office in luxury vehicles, and nobody bats an eyelash about it. The Bureau of Customs has been an altar of the secular devil that reformers since the People Power Revolt have tried to dismantle, replace, even abolish, but it has survived like the demon seed. The Bureau of Customs produces an acid so potent it will eat into the hardest of steels. Nicanor Faeldon and Isidro Lapena are only the latest proofs of this. Supposed to be exemplars of military men in uniform who are able to withstand temptations, and who repudiate those in the military and civilian sectors of government who are corrupt. They have become malleable putty in the hands of Rodrigo Duterte.

If two military men, the best of the lot and reputed to be the ones with integrity and leadership get corroded, is the whole military capable of withstanding the corrosive juices in the Bureau of Customs. At last, Duterte may have found the Achilles Heel of the military.

Early during Martial Law, Dr Clarita Carlos and I were involved in designing a course for Customs Attaches, as part of the Marcos Regime’s attempt in the early days to reform the Bureau of Customs and make it less vulnerable to corruption. One of the schemes taken was to field newly commissioned PMA graduates and other young military officers to the Bureau. Who can fight against the logic that those who have been freshly trained to fight and die for their country will be able to fight the temptations of corruption even in a snake-infested bureau like the Bureau of Customs?

Sure, the young military officers stood their ground, and could not be bribed. But in a few months, we found out that getting to them is just a matter of currency. They will not take money, but when young, sexy, booby mestizas turned up to insinuate themselves in their schedules and their intimate spaces, the military-fortified Bureau of Customs crumbled.

I pity the military officers and men who, like sacrificial lambs, will be sent to the Bureau of Customs. The problem with military men is that they develop a sense of derring-do attitude. They will take any hill, if ordered to do so, even if it is a Customs hill that is so complicated they would not know what the core business of the agency is, and the dangers and risks lurking in every corner and embedded in every innocuous looking transaction.

Worse, they will be the very trojan horses for the military’s entry into civilian governance. All it takes is a whiff of the explosive sensations of wealth, women, and war fighting, no matter how bogus the latter.

If the military cannot be plied with Glocks, maybe they will take unexplained wealth for everybody involved, if sugar coated and offered in the form of a patriotic duty to the nation? This should be the highest level of that phenomenon now known as “na-Duterte.” Turning the whole military, an institution for protecting the people, into an unsuspecting, ultimately savage “bantay-salakay.”

There is time to pull from the brink. But who will do it?

(The author,Dr. Segundo Joaquin E. Romero, Jr. is presently President of the Universities and Research Councils Network in Innovation for Inclusive Development in Southeast Asia (UNIID-SEA), a regional network engaged in development projects for the poor.)