BACACAY, Albay — Flooding has worsened in the upland barangays of Cagbulacao and Manaet in this town, where residents and local officials are searching for long-term solutions to what they say are the result of a major infrastructure project.

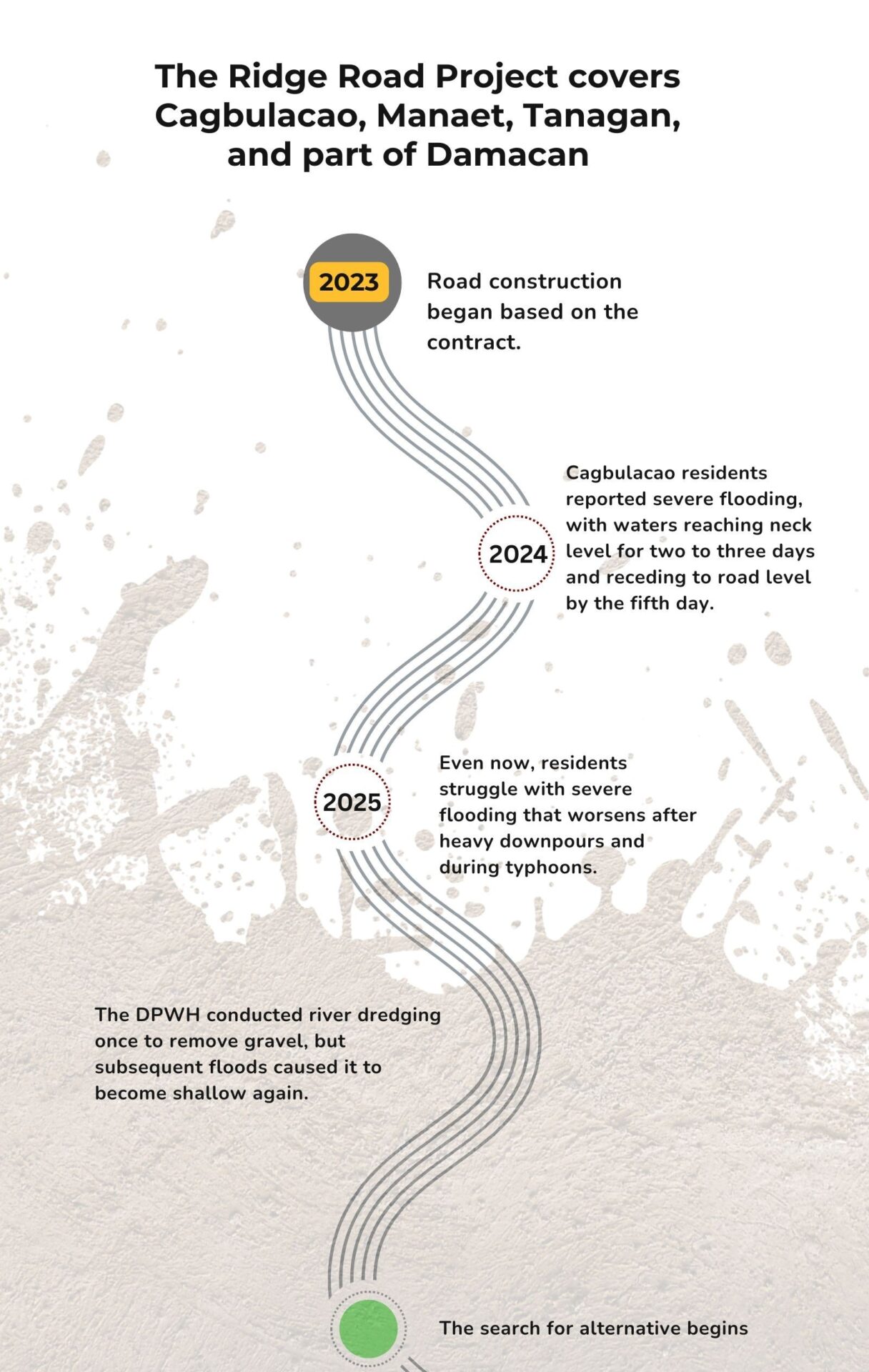

For many, the turning point came after the construction of the Cagbulacao–Tanagan Ridge Road, a billion-peso project intended to connect remote communities. Residents argue the road cuts through natural drainage paths, altering water flow and sending runoff directly into farms, homes and public facilities.

“Dati po hindi ganito,” said Cherryl Barlas, a 47-year-old single mother whose home has flooded repeatedly. “Makamondoon asin makahibihibi an nangyayari digdi… Sana po mahiling man nin mga kinauukulan an sitwasyon mi digdi (It’s painful and distressing. I hope authorities can see what we’re going through).”

Barangay officials share the concern. Councilor Gerlie Bandola said upland roads should have been built with proper slope protection and drainage, while Chairman Erni Bongadillo noted that P100 million originally meant for the 1.8-kilometer Tanagan–Manaet Road was redirected to the ridge project.

The first road remains unfinished, and during heavy rain, the route becomes slick and difficult to traverse, worsening isolation in the area.

Turning to nature-based solutions

Despite frustrations, residents have begun to show interest in ecological approaches alongside infrastructure. One option they’re eyeing is vetiver grass, a plant known for stabilizing slopes. Its roots plunge three to four meters deep—strong enough to anchor soil like mild steel—and reduce sediment runoff.

The Vetiver Network International (TVNI) notes the plant survives drought, flooding, heat and poor soil, making it appealing for flood-prone communities.

Jonop, Malinao: A test case

Bicol has already tested vetiver. In Barangay Jonop, Malinao, residents partnered with non-government Tarabang sa Bicol, Inc. (TABI) to construct a 160-meter seawall using sandbags and more than 10,000 vetiver slips. The P900,000-worth project, funded by the World Food Programme, provided temporary jobs and aimed to protect 200 families.

“Jonop is flanked by two large rivers, and a vast ocean lies in front of it,” a TABI representative explained during a field visit. TABI Executive Director Aubrey Versoza stressed the project formed part of its climate adaptation program.

In a September report, Barangay Chairman Willy Casia told BicoldotPH that the nearby river had already consumed nearly a kilometer of land due to weak flood management and stronger typhoons. One housewife added that each flood sweeps away their chickens and stored rice.

TABI said the seawall would stabilize within six months, this December, and urged mangrove planting to reinforce protection.

But when Super Typhoon Uwan (international name: Fung-wong) struck early November, it destroyed about 70% of the vetiver plantings, including the nursery. TABI called it a reminder that nature-based defenses demand sustained care and careful timing, including the release of funds.

More test examples from Tabaco City

Tabaco City offers more perspectives through different uses of vetiver grass. A study by researchers Marco Stefan Lagman and Melchora Abonal from the Central Bicol State University of Agriculture (CBSUA) documented how the city turned to vetiver as a low-cost, community-led fix.

In 2021, when liquid waste contaminated deep-well water near the public market, vetiver was planted in affected areas. “The water from the tap that was sourced from the facility’s deep well had again become clear,” Michael Brizuela, a city environment officer at the time, told the authors in 2022.

The city later built an *80-meter bio-engineered seawall on San Miguel Island using vetiver, sandbags and tree cuttings. It cost about one-tenth of a concrete seawall and relied largely on local labor. By early 2023, residents reported reduced tidal flooding.

In Brizuela’s words: “Residents no longer experience the inconvenience of high tide waters inundating their homes. They also now feel safer and are more hopeful that the said structure would protect them and their properties from future storm surges.”

The city government initially sourced its vetiver grass from CBSUA, which began introducing the plant to the region after a 2017 research collaboration with the Department of Agriculture. This effort later led to the establishment of a research center dedicated to expanding vetiver-based solutions for climate resilience and livelihood in Bicol.

Despite the initial wins, skepticism remains. Reynaldo Martirez, head of Tabaco’s City Disaster Risk Reduction Management Office, said in a phone interview that vetiver requires continuous care, leading some households to lose interest. Yet the community maintains a supply of slips that can be sold at P5 each with a minimum order of 1,000. Martirez believes vetiver could help Bacacay if planted strategically along ridge road slopes.

However, a barangay kagawad in Cagbulacao stressed, “We really need proper flood-control drainage.” Meanwhile, the housewife from Jonop, though appreciative of the community’s effort, admitted she still preferred a cemented structure.

Experts weigh in

Design anthropologist Pamela Cajilig explains that hard defenses often win support because they appear more durable, but evidence shows they can displace people, lock in poor choices, or even increase risk, citing expert references for her 2024 study on coastal seawall in Manila Bay.

Experts cited in Lagman and Abonal’s study caution against framing the issue as grass versus concrete. Consultants noted that protecting San Miguel Island from typhoon-driven tidal surges would require seawalls, but purely hard infrastructure would be costly to rebuild after damage.

Environmental planners proposed a bio-engineered seawall made of vetiver, coastal tree cuttings and sandbags with loam soil. City officials agreed to test the idea, and then-mayor Krisel Lagman suggested building a trial “green seawall” in a community affected by rising tides but not at high risk of storm surges.

This blended approach reflects guidance from the World Wildlife Fund, which stresses that flood-management strategies must be tailored to terrain, risk and scale.

Bacacay’s next steps

In Bacacay, residents say they are willing to try alternatives while waiting for suspended flood-control projects to resume. They see vetiver not as a miracle solution but as something they can begin with on their own while pushing for more comprehensive government action.

“If this can help even a little, why not try it while we’re waiting?” one resident said.

Whether through nature-based defenses, engineered structures, or a mix of both, residents believe the search for lasting solutions has only begun.

*180 meters from the interview with Martirez

* Mavic Conde, an editor at BicoldotPH, and Susan Balane, news and program director at Radyo Veritas-Legazpi, are VERA Files fellows under the project Climate Reporting: Turning Adversities into Constructive Opportunities.

This story was produced with the support of International Media Support and the Digital Democracy Initiative, a project funded by the European Union, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, and the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation.

The views and opinions expressed in this piece are the sole responsibility of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation, and International Media Support.