On the day the island of Luzon was put on lockdown on March 17, Henry “Hedel” Dela Cruz Jr. walked nearly five kilometers to claim his guarantee letter or GL at the Philippine Charity Sweepstakes Office (PCSO) in Quezon City.

Dela Cruz—who has chronic myelogenous leukemia, an uncommon form of bone marrow cancer—needed the GL to help cover the costs of his chemotherapy medicines. His long-awaited appointment, however, fell on the first day of the enhanced community quarantine to curb the spread of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

“Wala akong personal na sasakyan at dahil naka-schedule ako ng March 17, kailangan ko mapuntahan iyon dahil paubos na ang aking gamot,” Dela Cruz told VERA Files. He added that the document waives about P10,000 from his monthly P16,000-bill for capsules.

(I don’t have a personal vehicle, and because I was scheduled [to get my GL] on March 17, I had to go there because I was running out of medicine.)

He might have walked the whole 11 kilometers to get to the PCSO at the Lung Center of the Philippines coming from his house in Antipolo City, Rizal had not a good samaritan in a black car given him a ride halfway through his journey.

Dela Cruz is one of two cancer patients who made national news in March for having braved the roads on their own amid the suspension of public transportation during the ECQ.

For many others, however, this was not possible.

Based on the results of a survey of 155 countries in May done by the World Health Organization (WHO), many people who have non-communicable diseases (NCDs) like cancer “have not been receiving the health services and medicines they need since the COVID-19 pandemic began.”

Among the most common reasons cited was a “decrease in public transportation available.”

This hurdle became apparent early on in the pandemic, prompting some civil society organizations in the country to innovate and initiate free carpool service programs for cancer patients to safely transport them to treatment facilities.

Apart from this, however, doctors, patients and other cancer advocates have underscored the need to implement Republic Act No. 11215, or the National Integrated Cancer Control Act (NICCA) which, they say, would have provided patients with better access to cancer care services during the pandemic.

If it remains unimplemented by 2021, it will be two years of stagnancy for the law signed by President Rodrigo Duterte in February 2019.

‘Cancer won’t wait’

“Bilang isang immunocompromised, ang kawalan ng pampublikong transportasyon ang isa sa pinakamalaking balakid sa amin sa simula ng mga lockdown na ito,” Dela Cruz told VERA Files.

(As someone who is immunocompromised, the absence of public transportation is one of the biggest challenges for us [cancer patients] at the start of this lockdown.)

On March 18, a day after Dela Cruz made his journey to Quezon City, a woman named Cynthia Espiritu, also from Antipolo City and who had bone cancer and had lost a leg, walked from her home to a government checkpoint along Marcos Highway, the farthest her car service could go to pick her up. She was headed that day to the Philippine General Hospital (PGH) in Manila, about 20 kilometers from Antipolo City, for her monthly checkup.

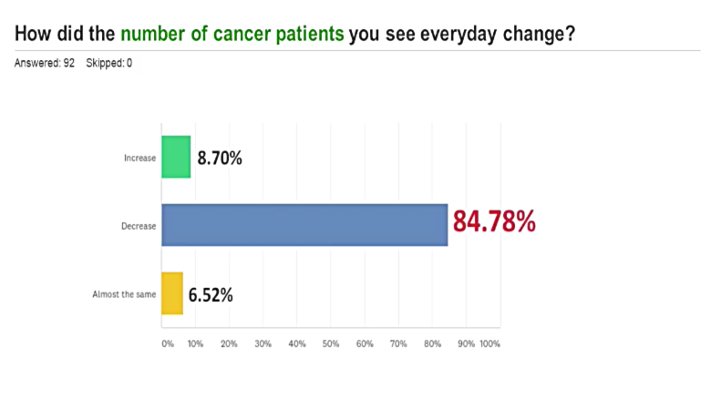

Dela Cruz and Espiritu are outliers. Based on a survey of 92 cancer specialists from the Philippine Society of Medical Oncology (PSMO), a group of board-certified cancer doctors in the country, nearly 85% said they observed a decrease in the number of patients they saw everyday.

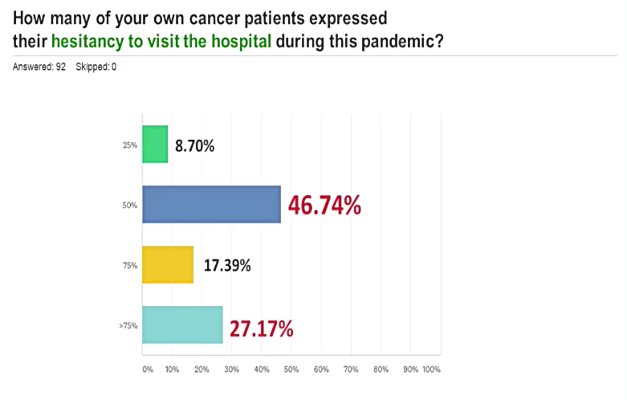

More than 90% said their patients had expressed hesitancy to visit the hospital during the pandemic. These findings were shared in a June 27 webinar by Hope from Within, the cancer advocacy campaign of healthcare company Merck Sharp & Dohme.

Made public in late June, the results of a survey of 92 doctors from the Philippine Society of Medical Oncology shows that oncologists saw fewer patients amid the COVID-19 pandemic, and many patients expressed hesitancy to visit hospitals. Screen grabs from June 27 Hope from Within webinar on “Cancer Care in the Time of COVID.”

Cancer patients identified limited mobility and worries of contracting COVID-19 as some hurdles they had to go through during the COVID-19 health crisis. In response to this, Cancer Coalition Philippines, a group composed of several cancer patient organizations, initiated a project in March called Mag-C-Kilos, a free carpool initiative for indigent cancer patients.

“It was borne out of the need for patients to get their treatment,” said Giselle Arroyo, a volunteer from breast cancer advocacy group ICanServe Foundation Inc. She managed the carpool program from April to May.

“Kasi hindi naman maghihintay ‘yung cancer, ‘di ba? Wala namang pakialam ‘yung cancer cells kung may pandemya. They will grow (Cancer won’t wait, right? Cancer cells don’t care if there is a pandemic. They will grow).”

The program connected indigent cancer patients in Metro Manila with volunteer drivers who would bring them to and from their chemotherapy sessions. Mag-C-Kilos helped a total of 157 cancer patients from March until it paused operations in August due to lack of funding, said Arroyo.

Majority of those served were children with cancer, seconded by breast cancer patients.

While not rolled out nationwide, the program was able to help patients in Metro Manila and neighboring provinces like Laguna, Cavite and Rizal. Arroyo said they were also able to refer some patients to local government units (LGUs) with “good health programs in place,” such as the cities of Taguig and Malabon and the province of Cavite, where LGUs themselves handled the transportation of patients referred by Cancer Coalition.

Another carpool service called CARe for Cancer ran parallel to Mag-C-Kilos, Arroyo added.

A partnership between ICanServe, Pfizer Philippines Foundation, Inc. and Grab Philippines, the program was established in 2019, even before the COVID-19 pandemic began, and offers carpool services specifically for breast cancer patients who are undergoing their first or second chemotherapy sessions in government hospitals.

Stigma of COVID-19 ‘worse’ than that of cancer

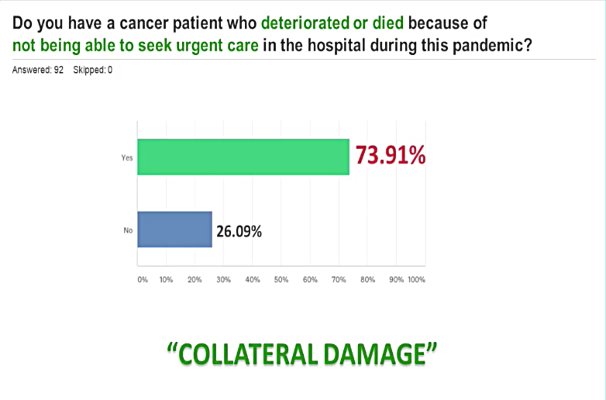

The PSMO survey revealed that over 93% of its doctors had a patient whose cancer had progressed, or had died after they were not able to seek urgent care amid the pandemic.

Nearly 3 in 4 doctors from PSMO had a patient whose condition worsened or had died after not being able to seek urgent care. Screen grab from June 27 Hope from Within webinar on “Cancer Care in the Time of COVID.”

Meredith Garcia-Trinidad, an oncologist based in Dagupan City, Pangasinan and chair of PSMO’s multimedia committee, explained that some patients had been afraid to go to the hospital for fears of contracting COVID-19.

“They are even more afraid to go when they have fever/cough/difficulty of breathing because 1) they don’t want to be tagged as a COVID-19 case — the stigma is really bad, even worse than the stigma of having cancer; or, 2) they don’t want to be alone since they will need to be isolated.”

But delays in treatment and diagnosis only mean bad news in the long run.

As COVID-19 quarantine measures have eased up compared to the beginning of the year, Garcia-Trinidad says she is seeing more patients now, with the necessary COVID-19 precaution measures in place as well as implementing a by-appointment system to avoid crowding and limit patient exposure.

But she makes this observation: “[N]ow I have been seeing double to triple the number of new cases I used to see—mostly those who are now symptomatic because they failed to seek [consultation] when the pandemic set in.”

It is for this reason that Arroyo, a cancer survivor herself, encourages cancer patients to continue seeking treatment.

“There needs to be an awareness among the cancer community that they can’t afford to wait anymore. Don’t be afraid of the hospitals,” she said.

“Kasi siyempre noong umpisa ng pandemya (Of course, at the start of the pandemic), everyone was scared. But now they have very good safety protocols in place, sabi nga nila ([and] as they say) the hospitals are much safer than the supermarket or the mall.”

In fact, it is not just cancer that has been greatly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Garcia-Trinidad added: “Most other diseases have been affected, unfortunately. Dialysis patients and other patients with conditions that can also present with cough/difficulty of breathing are also particularly compromised. Surgeries and procedures, as well as some diagnostic tests, are also more costly now because of the need for PPEs, swab tests, etcetera.”

WHO also mentioned this in its May survey results, saying more than half (53%) of the 155 countries had partially or completely disrupted services for hypertension treatment; nearly half (49%) for diabetes and diabetes-related treatment; 42% for cancer treatment, and 31% for heart emergencies.

Unimplemented NICCA law

Apart from transportation woes, if there was anything else that needed to be addressed, Dela Cruz and Garcia-Trinidad pointed to the same things: attending to the pre-pandemic cancer issues such as inadequate access to cancer screening, diagnosis and treatment, and insufficient financial support.

“Napakamahal magkaroon ng cancer sa Pilipinas, lalo na sa mga underprivileged at marginalized sector. Karamihan sa amin ay nangangailangan ng napakaraming regular na test at treatment, na napaka-expensive,” said Dela Cruz, who recently lost a job opportunity due to the shutdown of ABS-CBN in May.

(It’s very expensive to have cancer in the Philippines, especially for the underprivileged and marginalized sectors. Most of us need so many tests and treatments done regularly, which are very expensive.)

Garcia-Trinidad added that PCSO assistance “ironically went down to P10,000 per patient application.” A review of past news reports show the amount was as high as P50,000 per application in the past, and sometimes, even more.

As a result, some patients now have to shell out money from their own pockets in order to claim their supposedly free meds, which happened to Dela Cruz when his medicine stock ran out earlier this year.

“Dahil sarado ang mga [government] agencies I had to shoulder ‘yung cost ng gamot, at mahirap kumuha ng required documents from my hospital and doctor,” Dela Cruz said, recalling his experience in the early days of the community quarantine.

(Because government agencies were closed, I had to shoulder the cost of the medicine, and it’s very hard to get the required documents from my hospital and doctor.)

PCSO had stopped processing medical assistance requests the same day he got his GL, and only resumed operations a month later in April.

The NICCA, whose implementing rules and regulations have been finalized since August 2019, was created to make “cancer treatment and care more equitable and affordable for all.” One of its provisions is to create a Cancer Assistance Fund, meant to provide financial assistance to patients in need.

During the Senate deliberations on the 2021 budget in October, Sen. Nancy Binay, one of the authors of the law, questioned the absence of a line item for the Cancer Assistance Fund in the Department of Health’s proposal. The agency responded, saying they had included a P535-million budget for the Fund, but was yet to be approved by the Department of Budget and Management (DBM).

Apart from financial assistance, Garcia-Trinidad said the law could have provided “more major and satellite cancer centers to cater even to those from farther locations, lessening the need for travel.”

Despite worries and concerns, Dela Cruz holds out hope for a brighter future.

“Ang diagnosis ng cancer sa Pilipinas ay napakamahal, kaya madalas huli na ma-diagnose ang mga pasyente. Ang pagkakaroon ng mas komprehensibong batas para mapababa ang presyo ng mga tests na ito at treatment procedures ang magbibigay pag-asa sa maraming cancer patients.”

(Cancer diagnosis in the Philippines is very expensive, that is why diagnoses often happen too late. Having a comprehensive law to bring down prices of these tests and these treatment procedures are what will give hope to many cancer patients.)

(This story was produced after the author attended a Health Reporting course for journalists in Asia-Pacific organized by the Thomson Reuters Foundation.)