Elias Laxa’s An Alley in Sampaloc (1939)

Today’s Manila is the world’s most densely populated city filled with loud jeepneys, carcinogenic fumes, and filthy sidewalks — a far cry from its fame as the “Pearl of the Orient Seas” downgraded further to the inglorious title of “the gates of hell.”

But inside the Metropolitan Museum, a different view of old Manila unfolds: green and flowering trees, verdant hills, quiet neighborhoods, and a gentle pace of life as seen in the paintings of Elias Laxa, An Alley in Sampaloc (1939) and Malabon Market (1958); Lauro Alcala, Street Scene in Quiapo (1942); Miguel Galvez, Mandaluyong Panorama, 1947; and Jorge Pineda, Sungkaan (1942).

The exhibition “Fascination with Filipiniana: The Vargas Museum Collection” and “In the Wake of War and the Modern: Manila, 1941-1961” features a significant collection of the Jose B. Vargas Museum, University of the Philippines Diliman, curated by Patrick D. Flores.

“In the Wake of War and the Modern Manila, 1941-1961” explores how the collection of the Vargas Museum and the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas interconnects in a specific time frame, World War II and its aftermath, the rise of modern art in Philippine art history.

Jose B. Vargas (1890-1980) was the mayor of Manila under the Japanese Occupation (1941-1945) and the chairman of the Japanese-sponsored Philippine Executive Commission; he was also a Regent of the University of the Philippines. A connoisseur of Filipiniana, Vargas’ art collection spans from the late 19th century to the early 1960s, and “marks important turns in the relationship of Philippine art with Western-style painting,” as noted in a wall text.

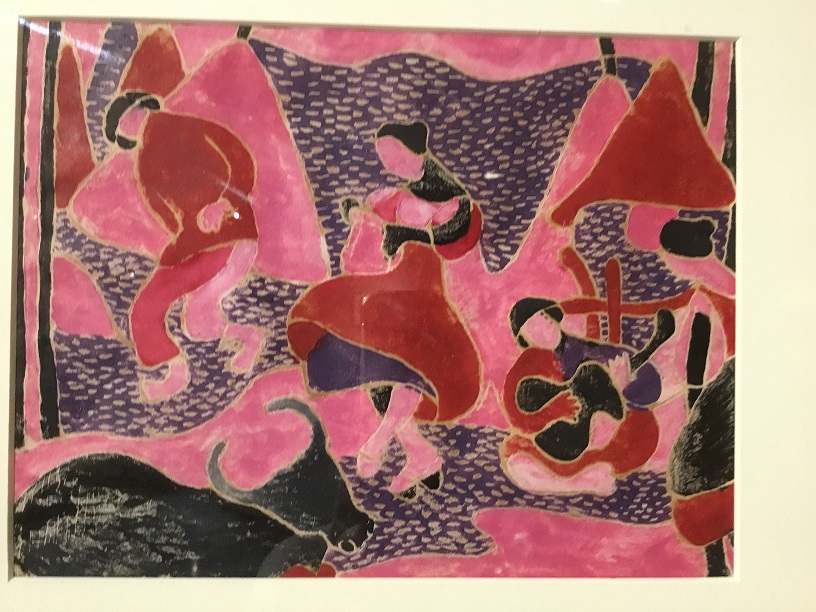

Hernando R. Ocampo’s The Contrast (1940)

Showcasing more than 45 artists, the exhibition reveals an overflow of paintings that reference the rural landscape: rice fields dazzling with sunlight, nipa huts surrounded by lush vegetation, flowering trees, good harvests, farmers and fishermen, azure skylines. Yes, absolutely idealized and postcard pretty. Interspersed with the bucolic scenes are still life of tropical fruits and studies of Aetas and Igorots.

Such a genteel life is disrupted by World War II with paintings that depict wartime Manila: the ruins of Intramuros, Fort Santiago, Manila Cathedral, the Legislative Building; Japanese soldiers on patrol, and sunken Japanese ships. Aside from Manila, Crispin Lopez’ Baguio Market (1943) depicts Japanese soldiers milling around and the Bombing of Bacolod (1942) by Jesus Ayco.

But even the scenes depicting ruin and destruction on canvas seem prettified and distant, and the horror of this war remains implied and unexpressed in some paintings on display, except for Ravaged Manila (n.d) by Dominador Castañeda, a graphic and painful work of war’s brutality on Filipinos.

Romeo Tabuena, Carabaos (1951)

Mabini Art Movement

A small section is devoted to the Mabini art movement, named for the Mabini Street area in Ermita where the so-called Mabini artworks, described as “an accessible picturesque style” catering to popular taste, have been sold since the 1950s.

Eight paintings by Fernando Amorsolo are part of this section that show fishing, cockfighting, and harvest scenes. Other works include Crispin Lopez’ The Sunrise, Juan Arellano’s A Forest, and Vicente Dizon’s Angelus. Dizon was the painter who won the first prize for After the Day’s Toil followed by Spain’s Salvador Dali in the Golden Gate International Art Exposition in San Francisco in 1939.

The Rise of Modern Art

Debates between the “conservatives” and the “modernists” continued in the aftermath of the war. The “conservatives” were those who favored the idyllic and classical style of painting as exemplified by Amorsolo and followers. In contrast, Victorio Edades (1895-1985) was a strong proponent of modernism in art, and all other artists who experimented with post-impressionism, abstraction, cubism, surrealism, art noveau and other innovative styles being played out in Europe and America in the early 20th century.

Nena Saguil, Harvest Season at the Farm (1954)

Beyond Labels

Walking through this exhibition, one gets a fresh look at the range of visual styles of Filipino artists in the early 20th century, from genre painting (urban and rural landscapes and scenes of everyday life) to early works in modern art, all in search of a distinct Filipino visual identity.

It is a moment to think about the early pioneers of the modern art form who forged their own paths and whose works were considered avant-garde, “subversive,” or “ugly” more than 85 years ago.

Beyond the labels of “conservative” or “modern,” the exhibition pays tribute to those who dared and persevered with their own vision and produced works based on their aesthetic sensibilities, in a specific time and place.

And there is something that always tugs our hearts: works that evoke the Philippines still make us feel warm, fuzzy, and nostalgic, no matter what.

The exhibition runs until July 21, 2018.

Dominador Castañeda, Ravaged Manila (n.d.)