By PABLO A. TARIMAN

THE coming concert of violinist Joseph Esmilla with the Manila Symphony Orchestra in Cebu City on Nov. 12 is as good a time as any to reflect on the golden age of violin music in the country.

THE coming concert of violinist Joseph Esmilla with the Manila Symphony Orchestra in Cebu City on Nov. 12 is as good a time as any to reflect on the golden age of violin music in the country.

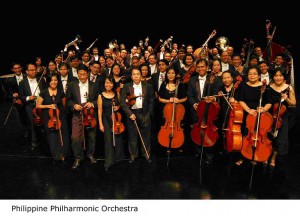

Esmilla will introduce the rarely played Korngold violin concerto for the Cebuano audience. He earlier premiered it in Manila to positive reception. He has also played the Sibelius violin concerto with the Philippine Philharmonic Orchestra.

The violinist, who was away from Manila’s concert scene for many years, proved he was more than just in good shape. He actually has a lot to offer artistically. In his last recital, his Brahms and Strauss sonatas were rock solid in execution, and critics said his playing has acquired a new luster.

Esmilla is the crucial link between two generations of violinists in the Philippines. He started violin lessons at age five with his father, violinist and conductor Sergio Esmilla Jr., as his first teacher.

He was also mentored by Oscar C. Yatco and Basilio Manalo, who were the first Filipino violinists to enter The Juilliard School where the young Esmilla received his Bachelor and Master of Music degrees under the tutelage of Dorothy DeLay, Masao Kawasaki and Jens Ellerman.

Like Esmilla, Diomedes Saraza Jr. made it to The Juilliard School this year and emerged as one of the two top freshmen of the school.

Saraza figured in an electrifying “First Violin Concerto” by Paganini with the Manila Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Christopher Poppen before the earlier landmark performances of Esmilla and Joaquin Maria “Chino” Gutierrez.

Saraza figured in an electrifying “First Violin Concerto” by Paganini with the Manila Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Christopher Poppen before the earlier landmark performances of Esmilla and Joaquin Maria “Chino” Gutierrez.

The last recital of Gutierrez, a prizewinner of the National Music competition for Young Artists, was equally astounding as that of Esmilla with a demanding repertoire of unaccompanied Bach and rarely heard sonatas of Robert Schumann and Eugene Ysaye.

Gutierrez is the great-grand nephew of Ernesto Vallejo, the country’s first violin prodigy.

The concerts of Esmilla, Saraza and Gutierrez brought back cherished memories of the unforgettable era of the violin in the country.

Long before Esmilla’s time, the country has heard violin greats, which attested to the wide following of violin music in the country. Russian violinist Mischa Ellman was in Manila in the 1920s, followed by Jascha Heifetz in the 1930s, Yehudi Menuhin in the 1940s, Ruggero Ricci, Gidon Kremer and Vladimir Spivakov in the 1970s, and Victoria Mullova in the 1980s.

Esmilla’s father, Sergio Jr., was only 21 when he graduated from the University of the Philippines College of Music where he played in the first violin section of the orchestra that accompanied Menuhin, who was soloist in the Mendelssohn concerto.

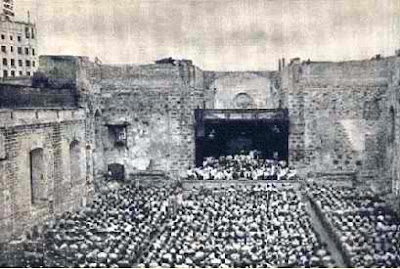

According to the older Esmilla, Menuhin gave approximately eight recitals at the University of Santo Tomas Gym, Holy Spirit in Mendiola, St. Cecilia Hall at St. Scholastica’s College, among others.

Menuhin was the first internationally renowned violinist to visit the country after World War II.

Menuhin was the first internationally renowned violinist to visit the country after World War II.

“From what I learned every concert was full house and that goes to show how high the interest in classical music was at that time,” the younger Esmilla recalled.

The Manila engagements of Kremer (he played with pianist Cecile Licad in one music festival in Germany three years ago) were courtesy of the National Philharmonic Society then headed by Redentor Romero, one of the country’s violin personalities.

Romero, who also became active as conductor and impresario, had taken extra efforts to bring into the country violin greats from abroad because he himself started his career in music as a violinist. A member of class ‘45 of the UP College of Music, Romero began his violin studies at 6 and became concertmaster of the Honolulu Symphony Orchestra at age 18.

He turned to full-time conducting and became the first Filipino to conduct the Moscow Symphony, London Philharmonic and the Beijing Philharmonic, among others. Romero’s contemporaries included Yatco and Esmilla’s father.

The late Manalo, who was behind the new batch of violin players of the new Manila Symphony Orchestra, opined that the new generation of musicians was a “thousand times” better than their predecessors.

Joseph Esmilla can only vouch for the dedication of the new generation of violinists represented by Saraza Jr.

He recalled, “Thirty-three years ago, I played my first full-length recital at

Philamlife Theater. The proceeds of that concert paid for my plane ticket to fly to the USA to audition at Juilliard.”

He continued, “For me, Saraza is the best of the young generation although quite underrated in our country. He happens to be the first Filipino to get accepted to Juilliard since I finished my master’s degree in 1988. That’s quite a milestone!”

Esmilla is indeed a formidable link between the old and new generations of violinists in the country. He carries what both sides of the generations hold dear: passion, dedication and astounding musicality.