With a Covid-19 death in the family, the unthinkable in Philippine life has happened. No wakes, and not even a last look and a last goodbye. Cremation must be done within 12 hours of death. Only an urn is handed back to the family. Such is the reality of the pandemic amongst us.

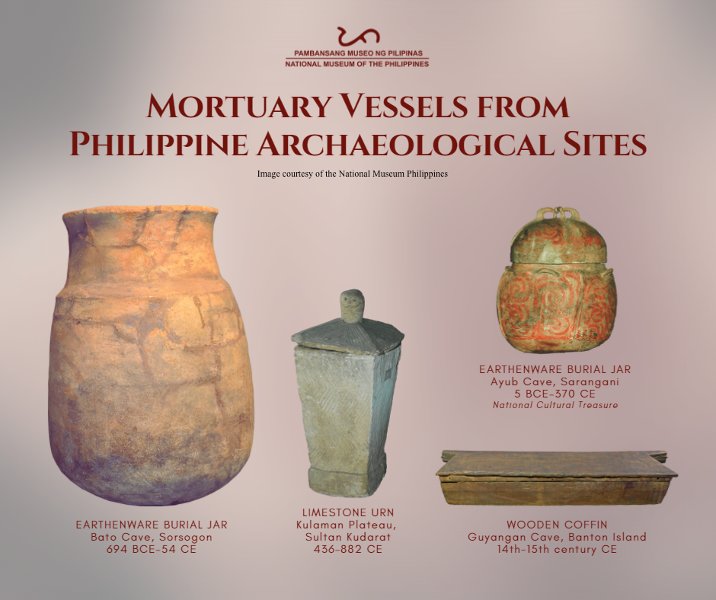

Today’s cremation urn is a reminder that thousands of years ago, we buried our dead in earthenware jars and other vessels. Caves and rock shelters provided that sacred space for burials.

A number of archaeological sites across the country have revealed primary and secondary burial traditions of ancient Filipinos and their views on the afterlife.

Earliest burials

So far, the earliest burial in the Southeast Asian region has been recorded at Ille Cave, Palawan, a burial site that included skinning, dismemberment, smashing of bones, cremation, and burial directly dated at 9,000 years ago.

The earliest known flexed burial (involving the bending of arms or legs) are those from Bubog Cave in Ilin Island, Mindoro dated 5,000 years ago and Duyong Cave and Sa’gung Rockshelter in Palawan, dated 4,500-5,000 years ago.

Sarcophagus Burial: The most familiar burial position, lying on the back, is seen in the one-thousand-year-old sarcophagus burial tradition in Mulanay, Quezon and the settlement-burial sites in San Remigio, Cebu. A sarcophagus is a box-like burial vessel made of stone and placed above ground.

Some 15 prehistoric stone sarcophagi carved from limestone have been found in Mt. Kamhantik, Mulanay. Rectangular in shape and without a lid, each sarcophagus contained another box-like or circular receptacle. The method of stone carving is similar with some Indonesian sites in Bali, North Sumatra, or East Kalimantan.

Limestone secondary burial jars in various sizes, shapes, and decorations have also been found in Kulaman Plateau, Sultan Kudarat, in the 1960s.

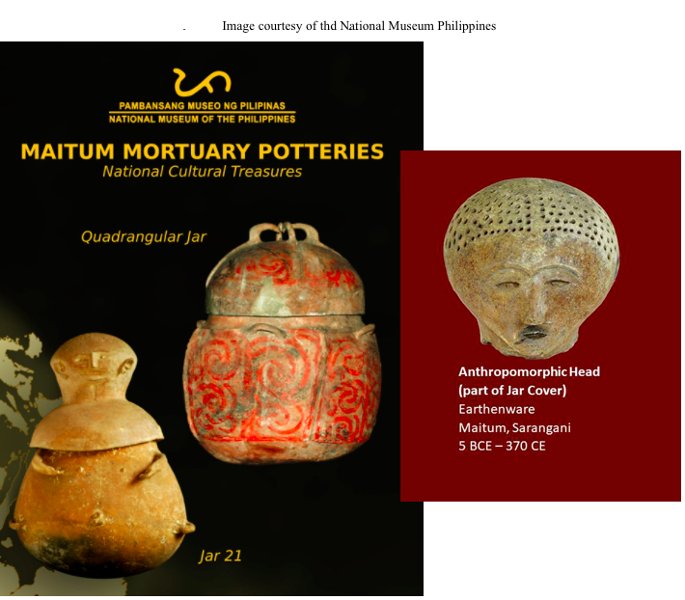

Maitum Mortuary Potteries: An exceptional collection of secondary burial jars, with human and non-human shapes, have been discovered in Ayub Cave, Maitum, Saranggani. The lids are shaped as human heads; the jar bodies have arms and hands as well breasts or genitals. Body ornamentations include distended earlobes, bracelets, arm rings, and headbands. Their distinct faces are like portraits of individuals, expressing a range of emotions.

Two jars, the most complete among the jars recovered in situ are known as Jar 21 and the quadrangle jar. Jar 21 represents a young male child with its genitalia; the quadrangle jar has four horizontal ear lugs and a body painted in red scroll design.

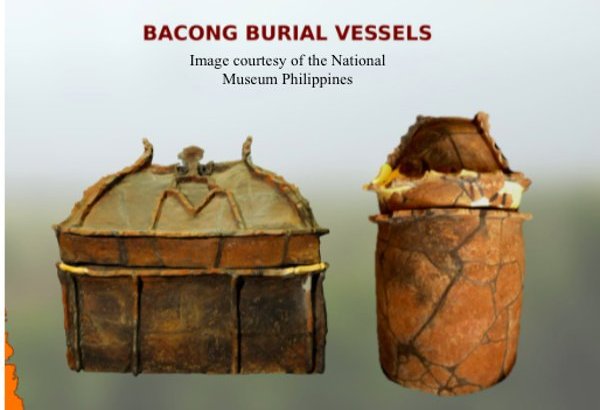

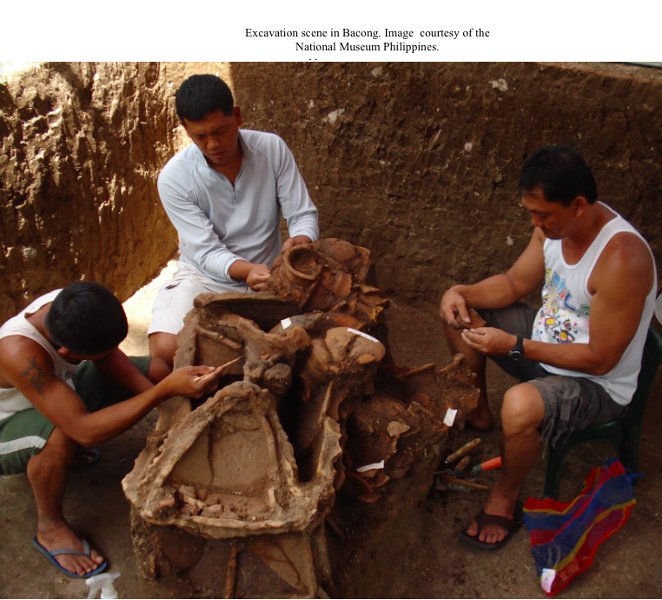

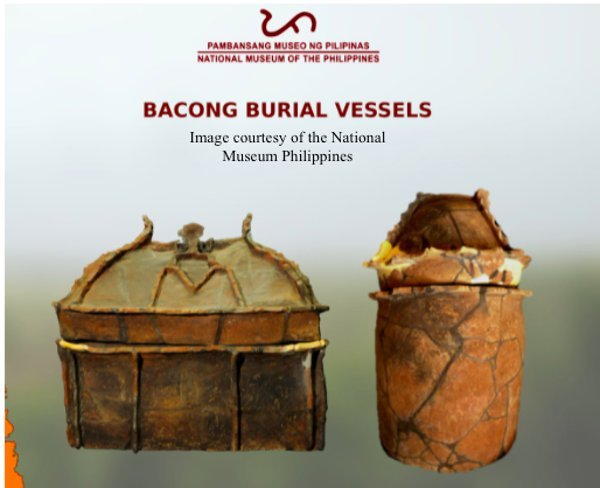

Bacong Jar Burials: In the 1970s, archaeologists from Siliman University and University of San Carlos had excavated some burial sites in Magsuhot, Bacong, Negros Oriental. Found were primary burial jars with the whole body of the dead in flexed or fetal position or dismembered, dated from 2100-1500 years ago.

Magsuhot has a rich source of clay for pottery, and a striking feature of its burial practice is the vast quantity of clay pots, between 70 to 100 pieces that accompany each grave.

The large jars, round or rectangular, exhibit a variety of designs that include fertility symbols or phallic forms. A stylized depiction of a cock’s head was found in some burial jars; a staff-like object with a cock’s head was recovered that may be a symbol of prestige or power.

Evidence of chicken and pig offerings at the bottom of the jar under the human remains was also recovered.

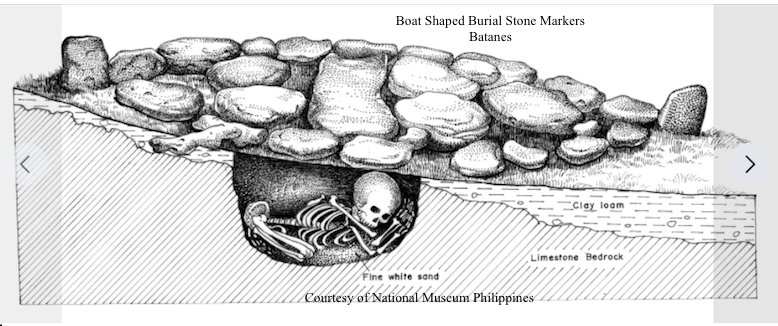

Boat-Shaped Burials: Another unique mortuary practice is the boat-shaped burial markers in Batanes, discovered in 1994. Stones are arranged to depict the traditional boat or tataya, with the prow and stern prominently visible. The deceased is buried underneath the mound on a limestone bed.

Interestingly, the current Ivatan people, who have a strong tradition of oral history and legends, do not have any account of this practice; there are also no written Spanish accounts. Its origins are still a mystery.

In Banton, Romblon, the wooden coffins, excavated in the early 1960s, are hollowed- out logs of hardwood molave, shaped into a boat with triangular lid, and usually carved with reptilian designs of snake, lizard, or crocodile. Found also were artificially deformed skulls with flattened foreheads in front and back, with gold ornaments at its base.

Similar burial practices have been excavated in Marinduque, Bohol, Palawan, and Masbate.

Prehistoric worldview

The variety of prehistoric mortuary vessels found in the country reflects complex belief systems, burial practices, and worldview long before 1521.

Ancient maritime culture in the archipelago is reflected in the belief that the souls of the dead become ancestors in afterlife and associated with boat coffins, reptile motifs, and the position of the coffins in caves that face the sea. Such types of receptacles are believed to facilitate the transition to the afterlife.

In many Southeast Asian societies, boats and maritime themes are part of daily life. It is not surprising that these themes are interconnected with dying and death as part of the everyday.