Human rights advocates call on the Duterte administration to address cases of enforced disappearances.

Forty desaparecido cases were reported in the first two years of the Duterte presidency, higher than the 31 reported in the six years of the previous Benigno Aquino III government, statistics from human rights groups Families of Victims of Involuntary Disappearances (FIND) and Asian Federation Against Involuntary Disappearances (AFAD) show.

Of the 40 reported victims of enforced disappearance, FIND was able to document 20 cases. Ten are still missing, one surfaced alive and nine were found dead.

In a press briefing to mark the 20th anniversary of AFAD June 8, Secretary General Mary Aileen Bacalso said in a statement, “This violent crackdown on illegal drugs has plunged the Philippines into its worst human rights crisis since the Marcos dictatorship with an unprecedented number of human rights violations and among which are enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings.”

Nilda Sevilla, co-chair of FIND, said the over 20,000 extrajudicial killings spawned by the current administration’s war on drugs have apparently pushed aside cases of enforced disappearances from public consciousness.

“While the drug war-related killings have overshadowed enforced disappearances, there are reports of the rise of the number of EJK victims who were first abducted and disappeared, before their lifeless bodies were found,” she said.

Desaparecido is the term used to refer to a person who has disappeared abducted, imprisoned or killed by government forces during the repressive years (1960s – 1980s) of the military juntas in Latin America.

In the Philippines, Republic Act No. 10353, the Anti-Enforced or Involuntary Disappearance Act of 2012, defines enforced or involuntary disappearance as “the arrest, detention, abduction or any other form of deprivation of liberty committed by agents of the State or by persons or groups of persons acting with the authorization, support or acquiescence of the State, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or by concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person, which places such person outside the protection of the law.”

FIND statistics covering the years 1983 to May 2018 show a total of 2,326 enforced disappearances.

Bacalso shared the difficulty of documenting cases of enforced disappearances because of the “atmosphere of fear created among the victims, their families, and witnesses.”

She said of the 2,326 cases of enforced disappearances, only 1,993 were documented. The whereabouts of the 1,166 are still unknown, and while 584 surfaced alive, 243 were eventually found dead.

FIND monitoring shows the years 1983 to 1985 have the highest number of incidents of disappearances followed by years 1987 to 1989. The period 1983 to 1985 was the peak of the campaign against the Marcos dictatorship; 1987 to 1989 was the period of the “total war policy” of the Corazon C. Aquino regime against insurgents.

There was a decline in the number of victims during the administration of President Fidel V. Ramos. The trend was maintained at the earlier part of President Joseph Estrada’s short tenure, until he declared an all-out war against terrorists, raising the number of victims to 63.

Under the administration of President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, there were 346 victims as a result also of her all-out-war against communist insurgents and terrorists. Under President Benigno S. Aquino III, FIND has recorded 31 victims. President Duterte’s administration already has 40 reported cases.

Commission on Human Rights Chairperson Jose Luis Martin “Chito” Gascon, referred to enforced disappearances as one of the worst human rights violations which persist in the country today.

“The Philippines, as well as many other countries in Asia and the world, has yet not been able to end this troubling phenomenon of the forcible removal of people – many perceived to be enemies of the state, and the constant denial that they are held captive by state authorities,” he said.

Gascon recalled the case of Jonas Burgos, a peasant activist and son of press freedom icon Jose Burgos, Jr., who has not been seen since he was taken by four armed men and a woman in a shopping mall on April 28, 2007.

University of the Philippines students Karen Empeño and Sherlyn Cadapan have also never been seen after gunmen abducted them from their rented house in Hagonoy, Bulacan where they were doing community work on June 26, 2006.

AFAD Chair Khurram Parvez, a human rights activist from India, shared his observation that Asian governments have a seemingly consistent policy of depending on the military in handling conflicts.

He said a military approach is not necessary in resolving the drug problem and that it would only give the government the power to “stifle dissent” and criminalize only those coming from the marginalized sector.

The human rights groups called for the proper enforcement of the Anti-Enforced or Involuntary Disappearance Act of 2012, which Gascon called a “dead law,” given that the “enforced disappearances continue, the people are not being surfaced, and the perpetrators are not being punished.”

The groups also called on the Duterte administration to ratify the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances, the lone international human rights treaty which the Philippines is still not a signatory.

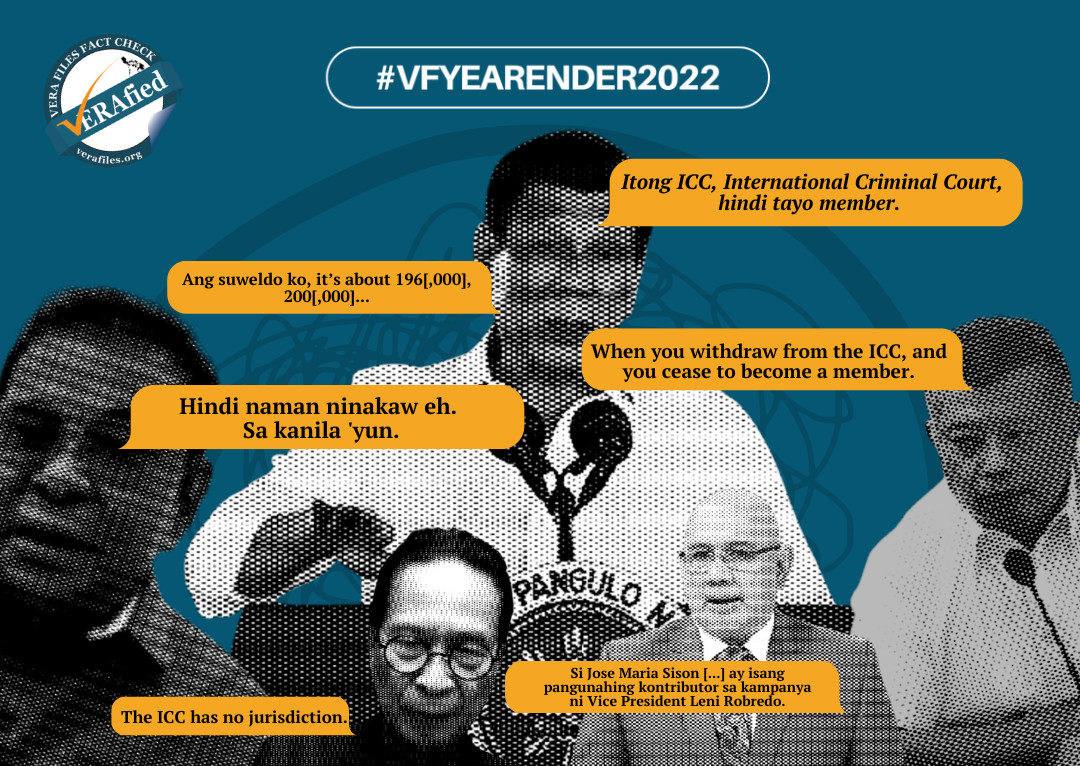

Gascon’s final call, however, was for the Duterte administration to “withdraw the withdrawal” of the Philippines from the Rome statute, the treaty which established the International Criminal Court (ICC).

The Duterte government withdrew March 14 from the Rome Statute after ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda opened a preliminary examination on crimes allegedly committed by the Philippine government in its war on drugs campaign, based on communication filed by lawyer Jude Sabio, Sen. Antonio Trillanes IV and Magdalo Partylist Rep. Gary Alejano.