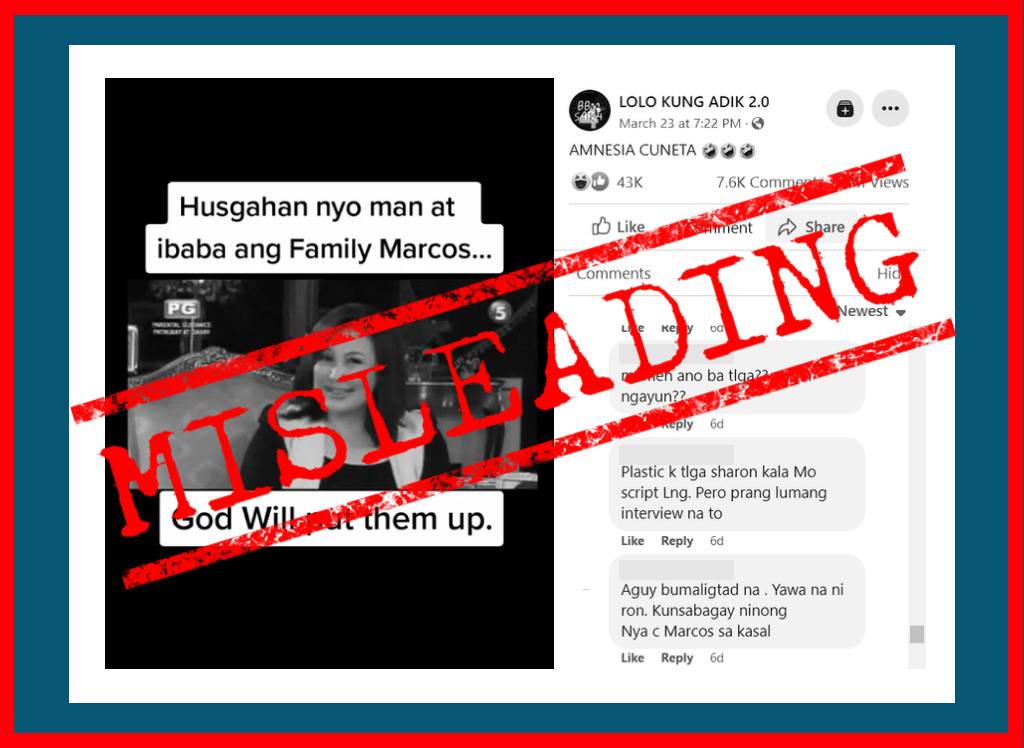

Will the Marcoses ever repent their sins of accumulating ill-gotten wealth and corruption? Even with world opprobrium, they have not.

As early as 1986 to 1988, not long after they were ousted from power, Ferdinand Sr. and Imelda Marcos were holding on to what they thought were their influential American connections to deliver them from the growing agony of their exile.

The context of that exile in the United States is an important throwback.

In February 1986 alone, two dictator-thieves were ousted in very unceremonious ways. Haiti president Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier and his equally imperious wife Michèle Bennett Duvalier fled the poor island nation they had impoverished to seek exile in France. Thousands of Haitians were killed and tortured during Duvalier’s presidency while the dictator and his wife maintained a notoriously lavish lifestyle. Like Imelda Marcos, Michéle became so powerful that she was known to dress-down cabinet ministers while her husband dozed off. The Duvaliers fled the country on February 7, 1986, driving through gunfire to the airport.

Just a little over two weeks later, it was the turn of the Marcoses to be ousted. The world had watched with awe at what turned out to be a peaceful revolution that earned the sobriquet People Power. There was thus a world magnifying glass on corrupt dictators and the trail of thievery and killings they left behind. That would have elicited shame and remorse.

But the Marcoses, who were accustomed to hiding their personal fortunes, made a big mistake. They thought that while they stuffed newly minted peso bills in crates, jewelry in Pampers diaper boxes, and mink coats in dozens of suitcases, the world was not looking.

It was. The U.S. Customs opened all their cargo, taking a few days to complete a record of what they had brought into the country. The days of entitlement had ended.

But not in the minds of the conjugal dictators. A few months after February, investigators started visiting them to get depositions – sworn statements in the presence of lawyers – on questions of racketeering or business dealings on U.S. soil derived from money illegally acquired. Imagine the death of the Marcos momentum: they were in power for over 20 years, adoring the pomp and perks of their unbridled authority. In the Philippines, they were treated with humble obeisance as king and queen.

And then suddenly, U.S. agents were bombarding them with questions about their ill-gotten wealth. In a flash, the pageantry was over. It must have been agonizing.

So Marcos and his wife thought it best to write their old “friends” Ronald and Nancy Reagan. One thing we can note in the tenor of their letters: while both acted with servility to the Reagans, they also believed they still enjoyed privilege.

A desperate man writing a letter asking for help would already indicate that despondency in the salutation.

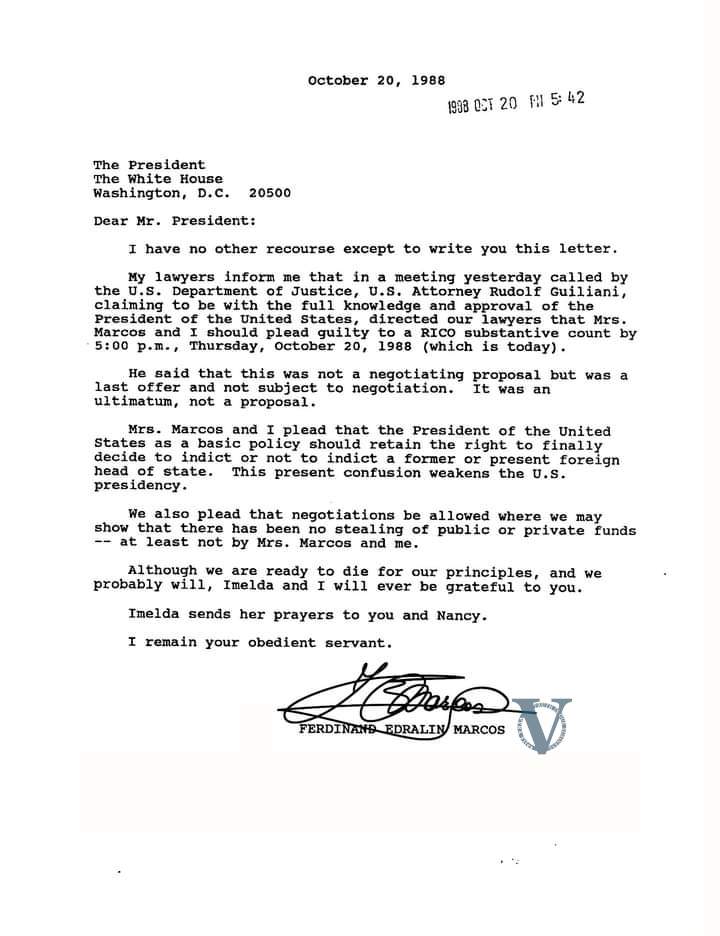

Marcos’s letter, dated October 20, 1988, begins with: “Dear Mr. President: I have no other recourse except to write you this letter.”

It continues with:

“My lawyers inform me that in a meeting yesterday called by the U.S. Department of Justice, U.S. Attorney Rudolf Giuliani, claiming to be with the full knowledge and approval of the President of the United States, directed our lawyers that Mrs. Marcos and I should plead guilty to a RICO substantive count by 5:00 p.m., Thursday, October 20, 1988 (which is today).” (N.B. Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act)

What did the dictator ask from Reagan? Two things: that Reagan exercise his right not to indict “a former or present foreign head of state” (obviously Marcos still could not accept the word “former”), and second that they be allowed to plead that they did not steal public or private funds.

Marcos adds: “Imelda and I will ever be grateful to you. Imelda sends her prayers to you and Nancy.”

After asking for entitlement and banking on what the couple had thought was their old friendship, Marcos ends with a rather condescending line: “I remain your obedient servant.”

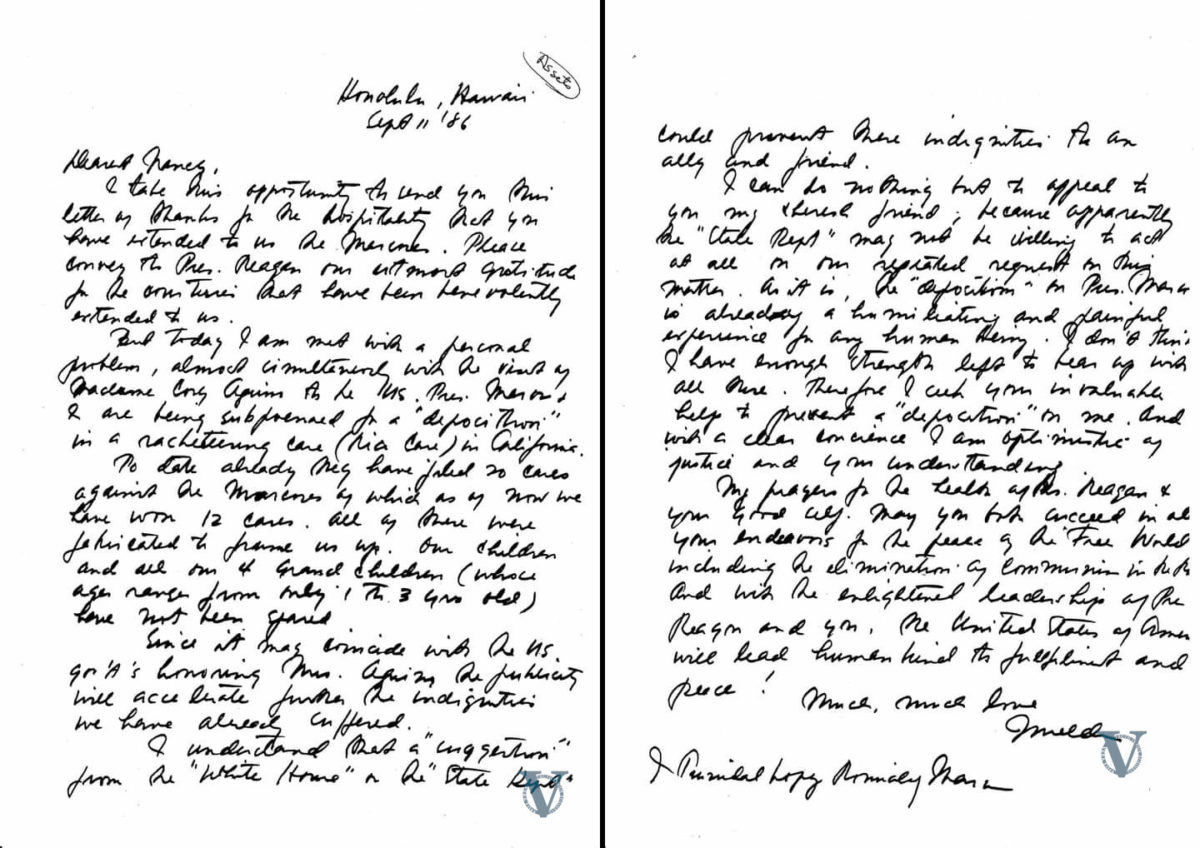

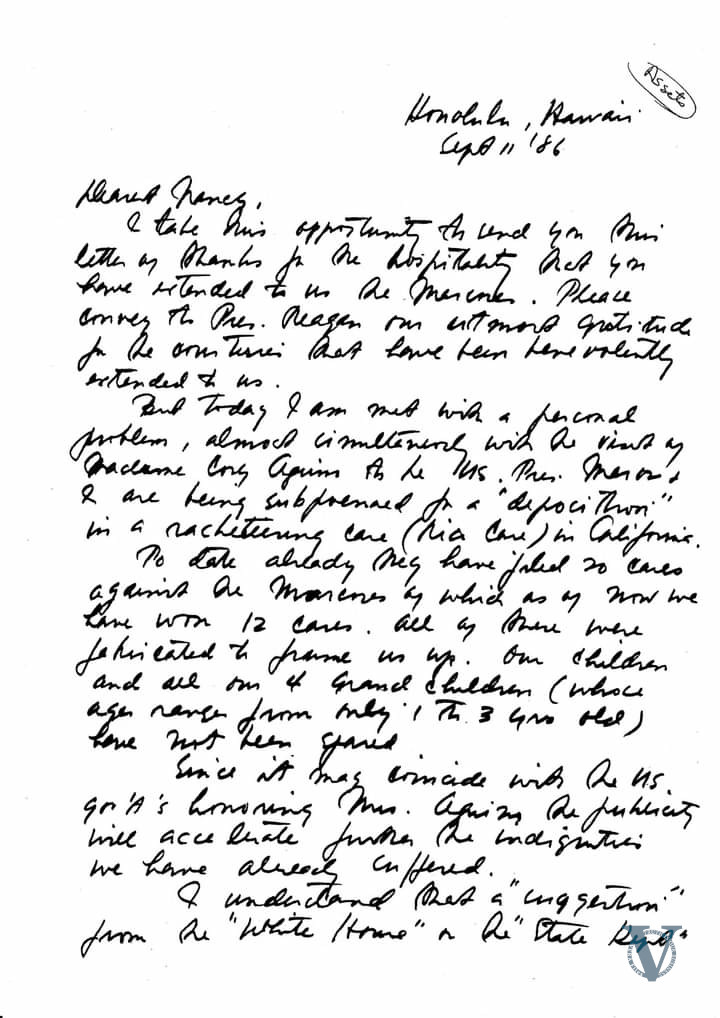

Imelda’s “Dearest Nancy” handwritten letter, in her typical tearful fashion, was written two years earlier on September 11, 1986. After thanking the Reagans for their hospitality, she begins her lamentation: “But today I am met with a personal problem, almost simultaneously with the visit of Madame Cory Aquino to the US.”

Notice that she does not refer to Aquino as president. They must have watched Cory Aquino on television addressing the Joint Session of the U.S. Congress, a first-time privilege accorded to a Philippine president by the Capitol. Imelda must have seen how many of the senators and congressmen wore yellow Cory dolls on their lapels. How she could have wished those were Imelda dolls.

Imelda narrates that already (as early as 1986), 20 cases had been filed against them (“all fabricated to frame us up”), not sparing their four grandchildren whose ages ranged from only 1 to 3 years old.

And then she invokes the now-familiar line they continue to invoke today – the damage to their family name: “Since it may coincide with the U.S. govt’s honoring Mrs. Aquino, the publicity will accelerate further the indignation we have already suffered.”

So she tells Nancy Reagan what she desires: “I understand that a ‘suggestion’ from the ‘White House’ or the ‘State Dept’ could prevent these indignation to an ally and friend.”

Prevent — how scared she was of bad publicity.

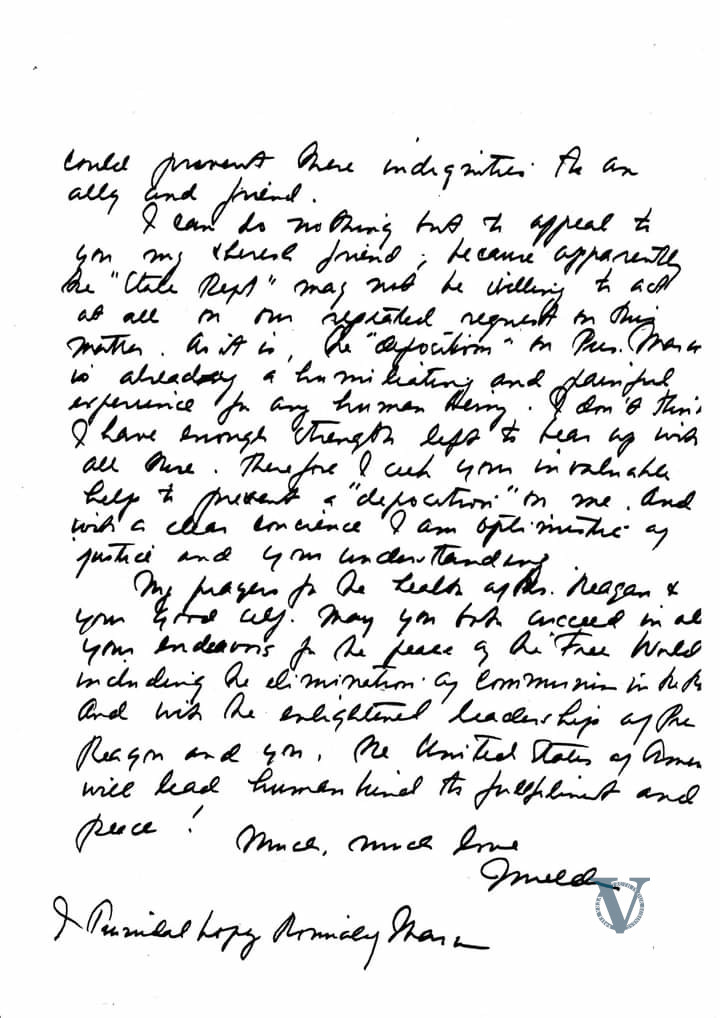

She continues with her plea: “I can do nothing but to appeal to you my dearest friend. As it is, the ‘deposition’ on Pres. Marcos is already a humiliating and painful experience for any human being. I don’t think I have enough strength left to hear up with all these. Therefore I seek your invaluable help to prevent a ‘deposition’ on me.”

In that last line, Imelda was more forthright and less diplomatic: she did not want to be investigated.

And before she ended: “My prayers for the good health of Pres. Reagan and your good self. May you both succeed in all your endeavors for the peace of the Free World including the elimination of communism” (so no references to her Mao visit she claims today when her charm supposedly impressed the Chinese leader so much). “Much, much love, Imelda.”

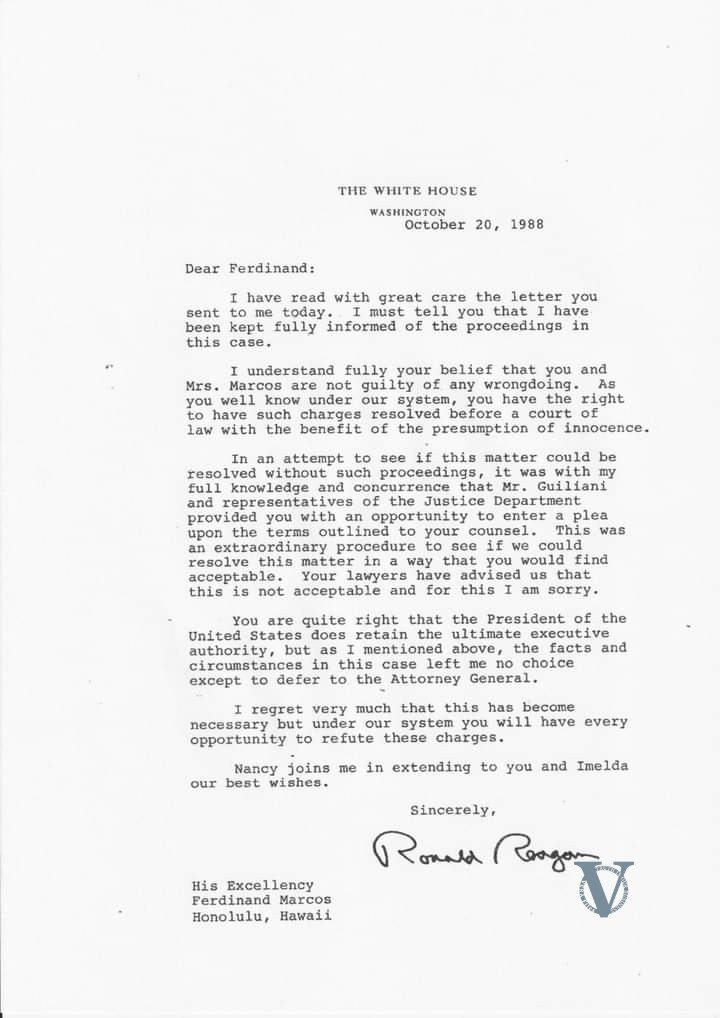

Now the Reagan responses. On White House stationery, Reagan responded with an icy no.

The summary points out: that the Marcoses could avail themselves of due process under the American justice system; that it was under his concurrence as president of the United States that the Marcoses plead guilty to the charges; that as president, he had deferred to this proposal from the U.S. Attorney General. And then Reagan’s valediction, which was probably hurting to Marcos: “I regret very much that this has become necessary but under our system you will have every opportunity to refute these charges.”

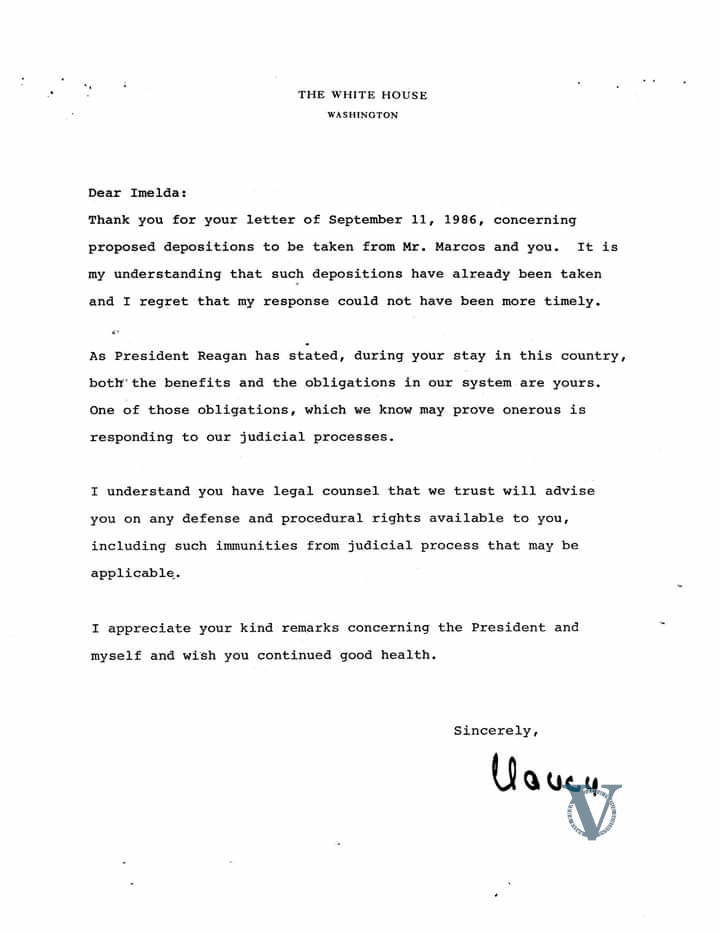

“Friend” Nancy’s response was en echo of her husband’s: “As President Reagan has stated, during your stay in this country, both the benefits and the obligations in our system are yours. One of those obligations, which we know may prove onerous is responding to our judicial processes.”

The Marcoses had never been tried in court at that point. On the contrary, they used the easily manipulated Philippine courts as weapons against their political enemies. The privilege they asked from the U.S. president was never given to the freedom-loving citizens of the Philippines. The U.S. depositions were extremely painful to their egos. From these letters alone, one can probably understand why today, Imelda wants a restoration of her family’s power after 36 years of insignificance.

Here is the ultimate lesson: of course, the Marcoses can have all the trappings of power back, but none of these can change their history as thieves of public money acquired through illegal means.

These letters are available to the public at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in Simi Valley, California. Credit goes to the Filipino artist Pio Abad who lives in the United Kingdom and has made it his signature to produce art based on the narrative of the Marcos loot.

Abad’s works are featured in his exhibits around the world. These caught the attention of a Filipino scholar at the University of Washington. Vince Rafael is a professor of history and Southeast Asian studies and author of a recent popular tome on Rodrigo Duterte, “The Sovereign Trickster: Death and Laughter in the Age of Duterte” (Duke University Press, Ateneo de Manila University Press).

As you can see, chismis had no place at all in these Marcos and Reagan letters.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.