From Australia to Zambia, OFWs have become part of the global landscape. Imelda Cajipe Endaya’s exhibition, Kahapon Muli Bukas revisits the Filipino woman as Domestic Helper, neglected, marginalized, and made invisible. It runs at Silverlens Manila until 14 February 2026.

Modern slaves abroad

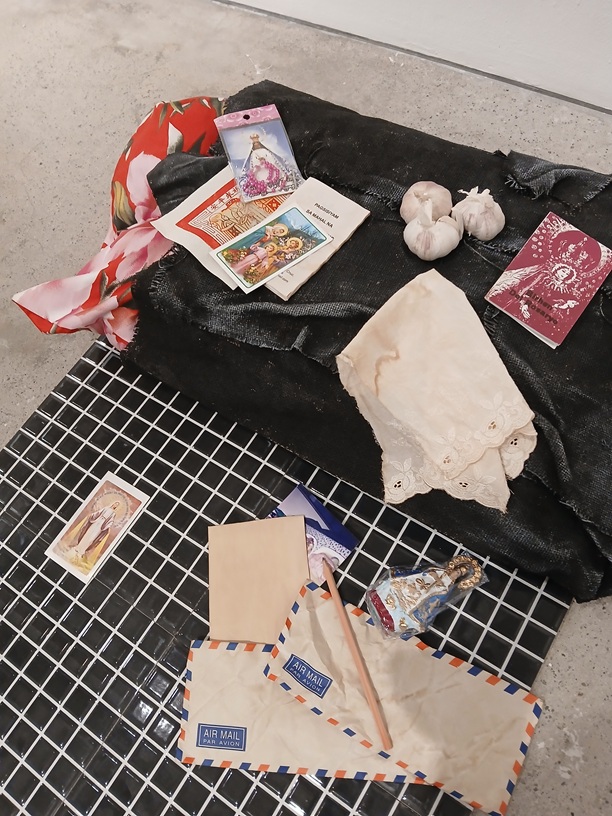

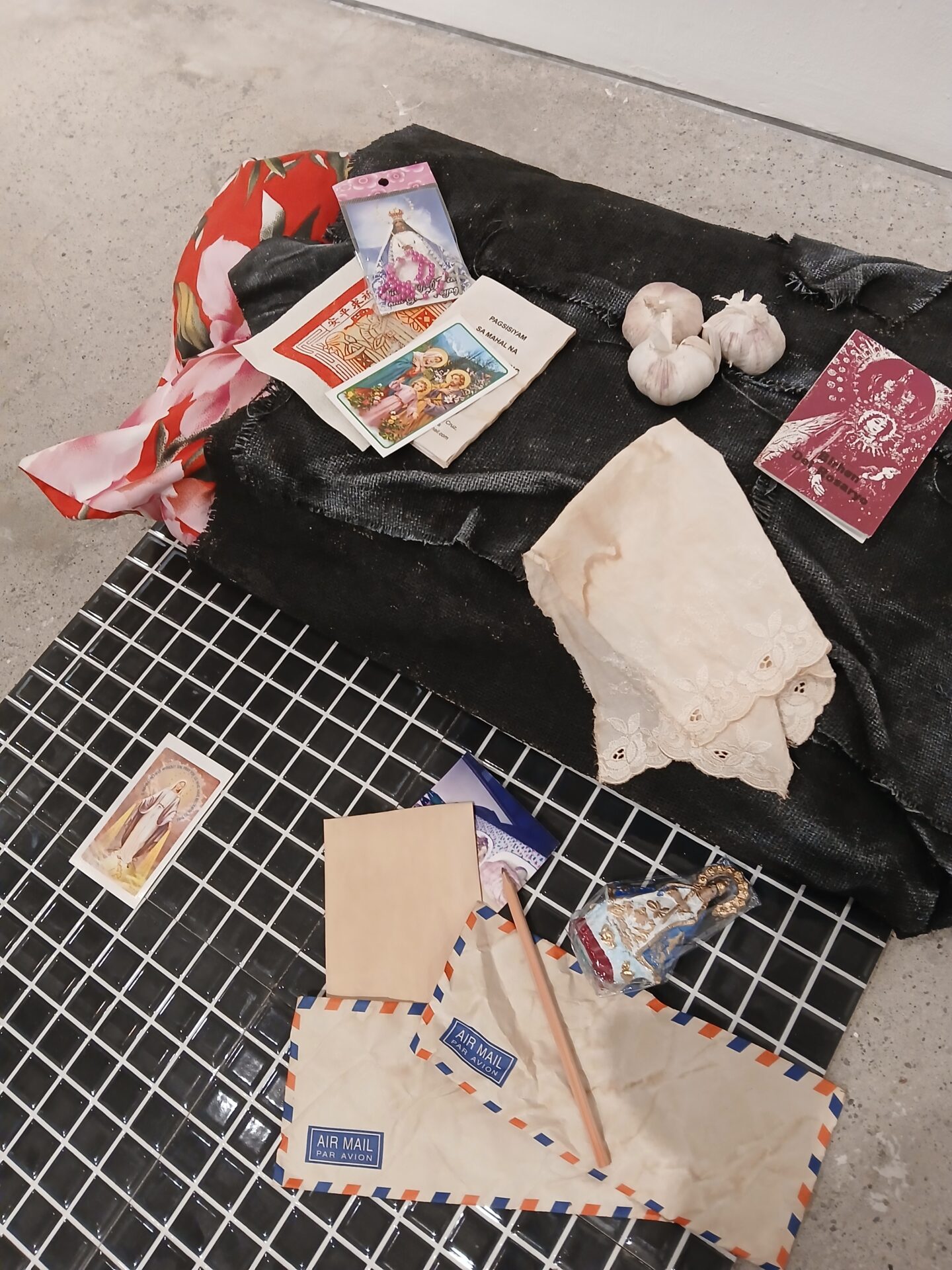

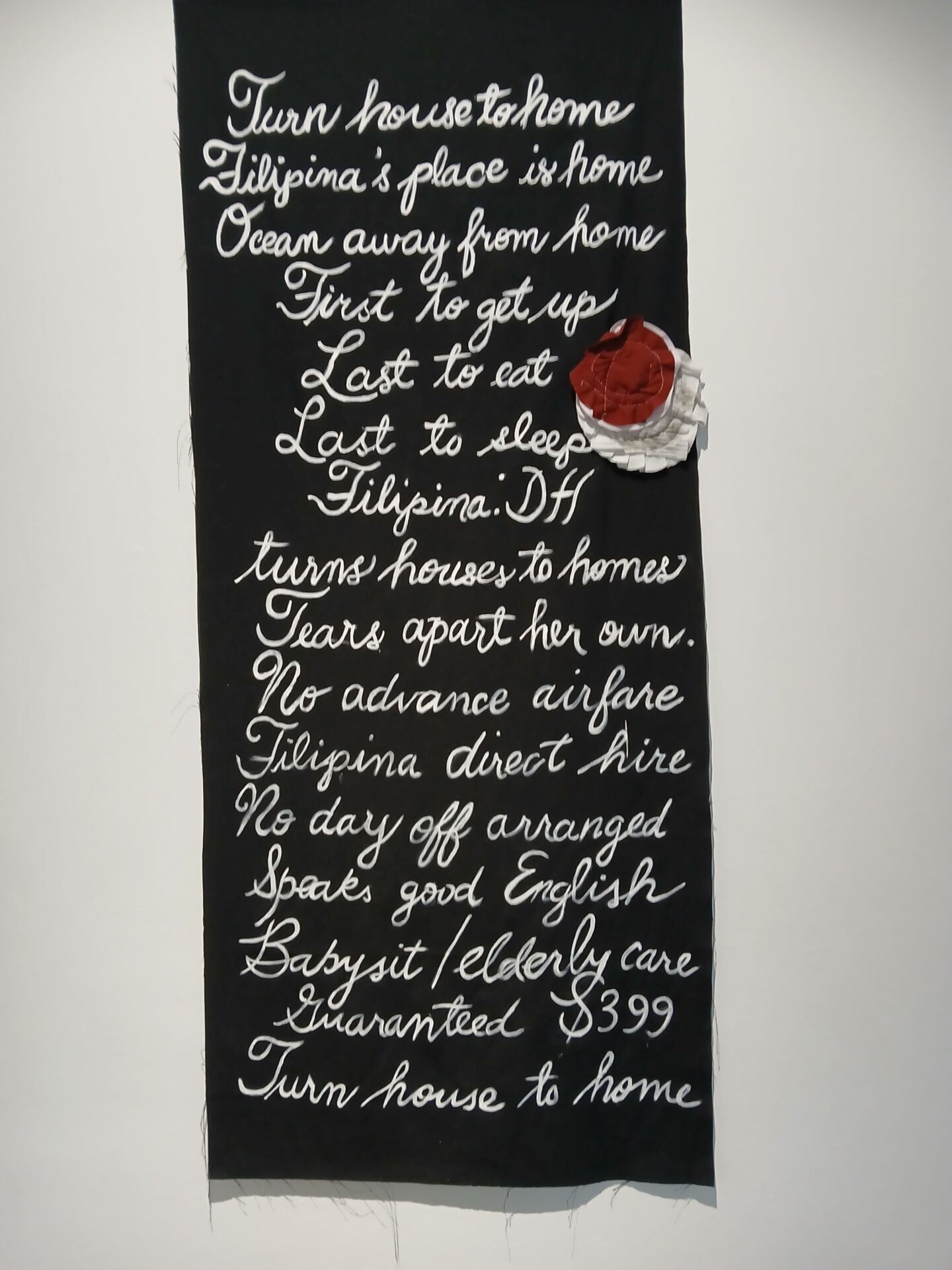

Endaya’s installation Filipina DH is composed of several pieces: A black blouse with the word “Dignidad” and a black apron with a pocket full of wooden clothes pegs. Cleaning tools taped and wrapped in black plastic: a mop, a broom, a dustpan, an ironing board emblazoned with the golden rays of the Sorrowful Mother. A wall of black cloth with Tagalog text lists a litany of issues: widespread poverty, high prices, government corruption, no jobs in one’s own country, migrants who sell their land, jewelry, and carabao as placement fee, and the proliferation of job scams. In short, how to become a slave abroad.

In the late 1990s, the work travelled from New York to Mumbai to Perth as part of Asia Society’s exhibition Contemporary Art in Asia:Traditions/Tensions.

After 30 years, Filipina DH is back in Manila; in its 2026 iteration, used suitcases and duffel bags are lined diagonally in front of the installation, lent by members of Kasibulan, a collective of women artists cofounded by Endaya in 1987.

Filipina DH was first exhibited in 1995 at the NCCA Gallery, when harsh and oppressive conditions and the lack of legal protection faced Filipino women as overseas workers. In that year, Singapore executed by hanging Flor Contemplacion and United Arab Emirates convicted 16-year-old Sarah Balabagan of killing her employer who tried to rape her.

Cases of abuse and maltreatment, sexual violence and rape, murder, and deaths in suspicious circumstances of OFW women have continued: Joanna Demafelis, 2018; Jeanelyn Villavende, 2019; Jullebee Ranara, 2023; and Jenny Alvarado, 2025.

Near the gallery entrance, white frilly aprons hang on a wall, projecting images of Filipino women workers with their faces covered: a respite from their work, posing in front of a verdant park, enjoying the warm summer air, or building a snowman.

Exporting labor

Using its people as export commodity has become part of Philippine government policy since the early 1970s. Filipino women comprise more than 50 percent of Overseas Filipino Workers (OFW), dubbed as “modern heroes.” In 2025, Filipino women accounted for over 57 percent of OFWs; a large portion of women works in unskilled occupations, mostly care work.

Filipinos abroad sent US$32.11 billion in remittances from January-November 2025, a 3.3 percent increase from the same 11-month period in 2024, says the Central Bank of the Philippines.

Dismay and satisfaction

Endaya notes that nothing has really changed, “the situation repeats itself…” Her satisfaction lies in fact that Filipina DH, made 30 years ago, is “still relevant today for sad reasons.” While technology has changed from prerecorded messages in cassette tapes to today’s instantaneous text messages and video calls through smartphones, the materialism continues, Endaya notes. OFWs shower their children with expensive goods like Nike shoes to make up for their absence; the children have lost affection and nurturance.

Other works

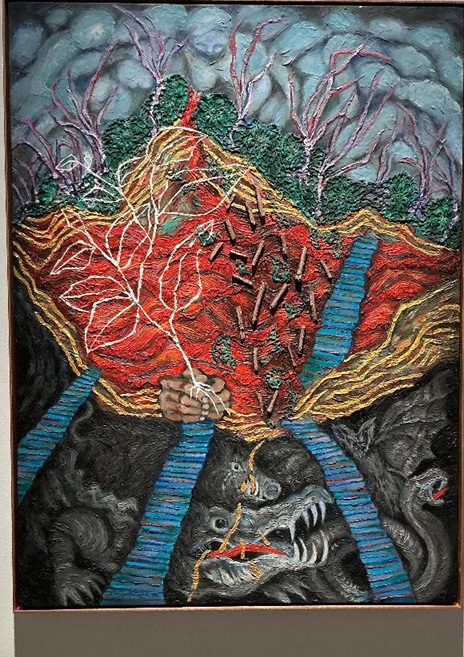

Other mixed media works in the exhibit include Delubyo (2023), Padugo 1521 (2021), and Bay-I sa Ika-5-Dantaon (2021-2022) address issues of social justice, religious oppression, and the existential consequences of climate change and environmental destruction. The ever-present crocodiles in her works represent man’s rapacious greed and corruption.

Endaya states that she “cannot end the canvas without saying something valuable.” Common themes in her work include social justice, women empowerment, and the nation.

In Endaya’s artistic landscape, the Filipino Woman takes center stage as an ancient priestess, healer, nurturer, comforter, and the eternal mother across generations, as she is in the past, the present, and the future.

A triptych, Bay-I sa Ika -5-Dantaon (2021-2022) depicts the past, the present, and the future collide amidst a lone indigenous woman with many arms, naked and standing tall, and covered by a golden lingling-o, a symbol of fertility and prosperity, amidst a raging sea. Her feet crushes some sea monsters below.

On her right, a woman with a toddler at her back takes a smartphone photo; on her left, a grandmother in traditional attire carries a plate of fish. Symbols across the centuries float in the background: a galleon ship, a satellite, the names of the disputed isles and shoals in the West Philippine Sea. The young child’s gaze meets the viewers: her bewildered eyes mirror an uncertain and turbulent future.

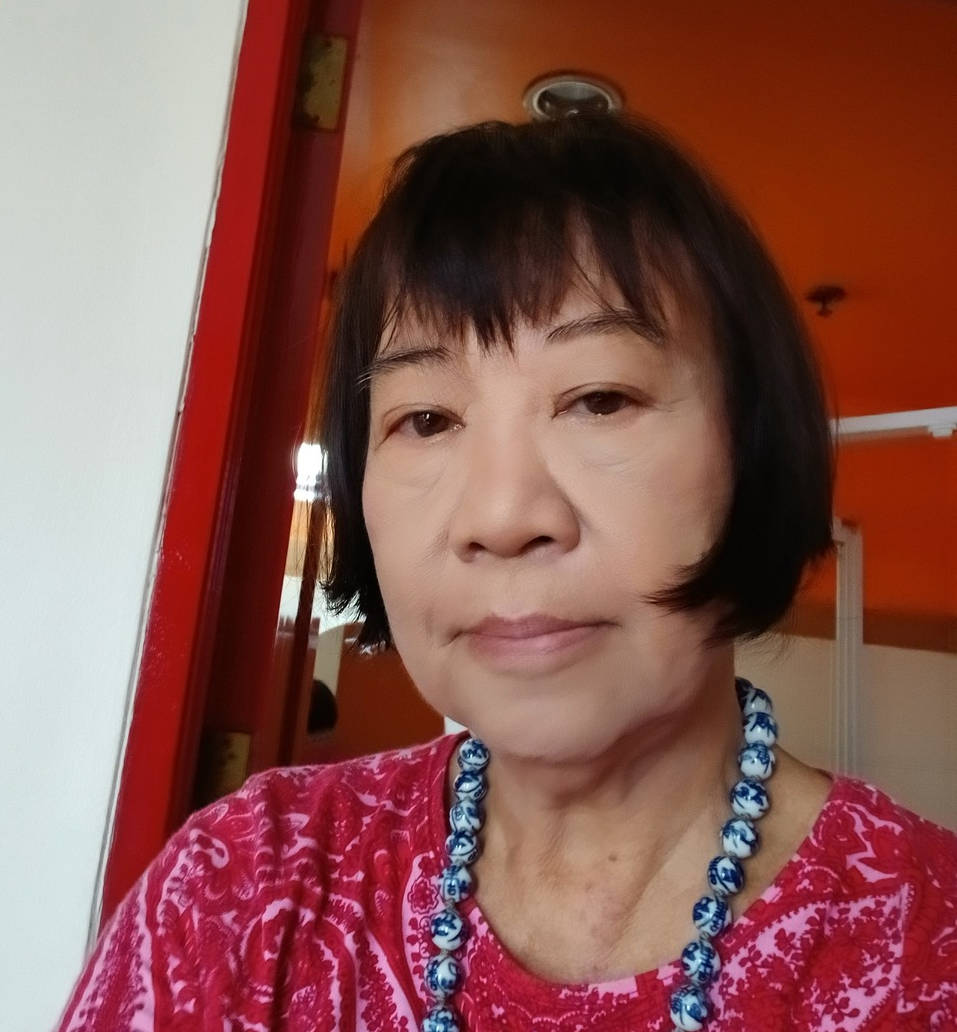

Imelda Cajipe Endaya (b. 1949, Manila)

Endaya is one of the artists in focus in Art Fair Philippines 2026 (6-8 February 2026) with Imelda Cajipe Endaya: A Votary’s Art that shows a selection of her prints and printmaking practice from her inventory of almost 300 prints.

As part of the Singapore Art Week 2026, the National Gallery Singapore presents Fear No Power: Women Imagining Otherwise, an exhibition of five contemporary female artists from the region that includes Imelda Cajipe Endaya, Philippines and artists from Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, and Thailand. Running until 15 November 2026, it honors their multifaceted roles, not only as artists but also as educators, writers, or community organizers.