In April 2018, the Philippine government ordered a six-month closure of Boracay, one of the country’s top tourist destinations located more than 300 kilometers south of Manila. Known for its powdery white beaches, the island, located in the central Western Visayas region, had turned into what President Rodrigo Duterte called a “cesspool,” and needed cleanup and rehabilitation.

Typical of events that capture public attention, the Boracay closure provided online disinformation creators a convenient peg for their ‘stories’.

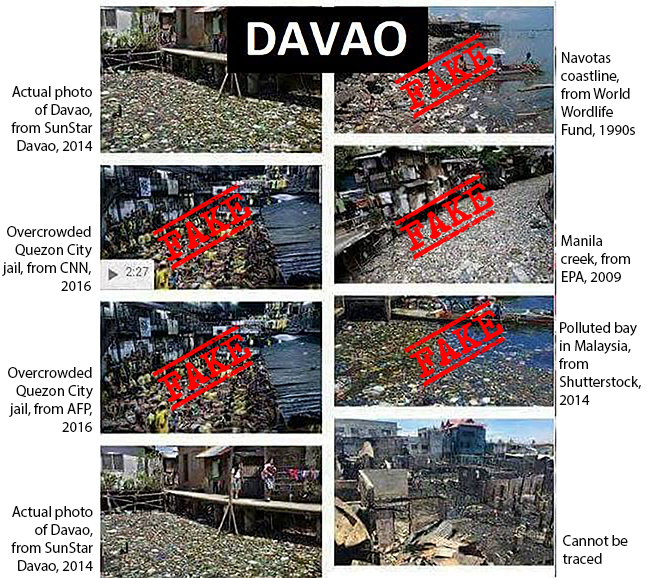

A Facebook page called Awaken Philippines deceived its readers by posting a collage using fake photos to portray southern Davao City, Duterte’s hometown of which he was mayor for more than two decades before being elected president in 2016, as being more polluted than Boracay.

The Awaken Philippines post, unlike most of the online disinformation debunked by VERA Files Fact Check, publishes content critical of the Duterte administration.

Yet it shares similar deception strategies, notably the scheming use of photos, which diligent users could discover as fakes or tampered with using a fairly easy online check: reverse image search.

Reverse-searching an image through Google Images or TinEye shows all the pages on the web where that image appears.

The idea is simple, but the technology allows online users to inspect, among others, if an image is indeed an accurate representation of an event and is not drawn from an unrelated incident or place.

Doing a reverse image search on the Awaken Philippines collage reveals that among the images purporting to be “Davao,” only the one on the top left is a real photo of the southern city, sourced from a 2014 newspaper report on pollution by ‘SunStar Philippines’.

The rest of the photos are:

- an overcrowded jail in Quezon City, used as a thumbnail of a 2016 CNN report

- a photo of the same jail, by Agence France Presse

- coastline shot of Navotas, shot by World Wildlife Fund photographer Jürgen Freund in the 1990s

- a creek in Manila taken in 2009, from the European Press Agency

- a polluted bay in Malaysia taken in 2014 by Shutterstock photographer Rich Carey

The bottom right photo could not be traced, but by then it becomes clear the Awaken Philippines post is fake.

“Fake news” creators also use videos – in fact more than photos or text – and being able to verify the authenticity of videos is an important, if not necessary, skill for social media users.

Many deceptive online content rely on clickbait headlines that claim to have video proof of an invented event. Checking if the story contains a video (many times, they don’t) or if the accompanying video bears the claim out (many times, they don’t) usually does the trick.

Some videos are trickier.

In September, a misleading two-and-a-half minute video supposedly featuring the country’s “first diesel-electric-submarine” made the rounds of social media – among the ‘information products’ online aimed at earning political points for the Duterte administration.

In this case, using a plugin called InVid allows users to analyze the video frame-by-frame, and then search where else across the web the corresponding frames can be found.

It turns out the supposed “first diesel-electric-submarine” video is not what is claims to be, but contains spliced clips of:

- a November 2015 Videoblocks clip of the missile submarine USS Ohio in Malaysia

- a November 2015 Shutterstock clip of the same ship; and

- an October 2017 video of the United States Navy’s nuclear-powered Virginia-class submarine, posted by Youtube channel US Defense News.

(This story was produced under the Southeast Asian Press Alliance 2018 Journalism Fellowship Program, supported by a grant from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights [OHCHR]. The views expressed herein can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of OHCHR.)