National Artist for Literature Frankie Sionil Jose enjoying his favorite boiled, greaseless peanuts in a Chinese restaurant in Ermita in the vicinity of La Solidaridad, the iconic bookstore he owned.

He came at the right moments in my life, saving me from myself and my impulse towards self-destruction. On my last year in college, I paid him a visit in his cubicle on the top floor of Solidaridad Bookshop in Ermita. I handed him a copy of a collegiate magazine where I had written an essay chronicling my bout of depression that led to a suicide attempt, and how I survived the episode.

F. Sionil Jose asked me to take a seat beside his desk while he read the article. Then he said he had a confession to make—that back in his own college days, when he flunked a major science subject (he enrolled as a premed student at the University of Santo Tomas, with the ambition of becoming the top neurosurgeon in the country and thereby becoming a millionaire), he got disqualified from his course. He went to the railroad tracks with the intention of meeting an oncoming train, but before he did that, he met with his English professor (I’ve forgotten the name) who encouraged him to shift to a writing course. He did, and the rest makes for a significant part of the history of Philippine literature in English.

I was soothed that even a man like Frankie who, for the longest time, I never addressed with an honorific like Kuya, Manong or even a familiar Tito, also went through the dark night of the soul.

But being a diagnosed bipolar and taking my meds religiously have not spared me from further depressive episodes. In March 2015, I was hit so hard by another emotional downturn that I contemplated jumping off the balcony of a 22nd-story office where I had just finished interviewing a musician. Something pulled me back (a higher force, maybe?), and I wiped away my tears and went home. When I opened my laptop, I found an email from the bookshop in Frankie’s stationery and handwriting.

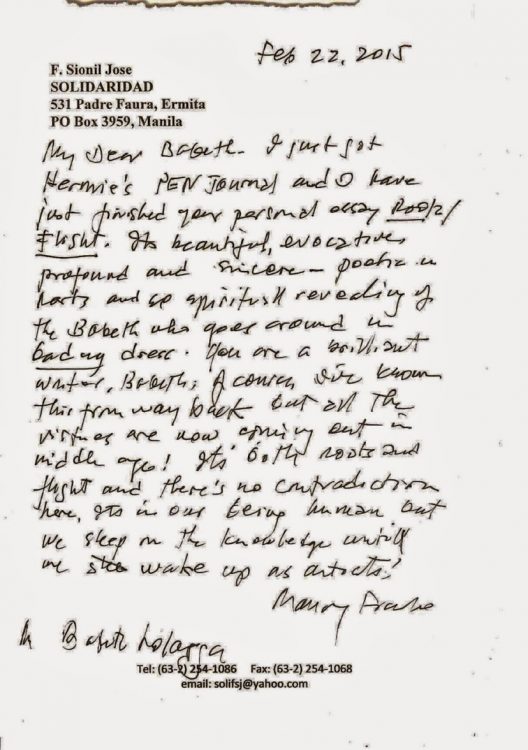

The letter read: “My dear Babeth, I just got Hermie (Beltran’s) PEN Journal and I have just finished your personal essay Roots/Flights. It’s a beautiful, evocative, profound and sincere—poetic in parts and so spiritually revealing of the Babeth who goes around in baduy dress. You are a brilliant writer, Babeth. Of course, I’ve known this from way back but all the virtues are now coming out in middle age! It’s both roots and flight and there’s no contradiction here. It’s in our being human, but we sleep in the knowledge until we wake up as artists! Manong Frankie”

I broke down weeping, thankful for his words which seemed to be the grace that was awaiting me and pulling me from another limbo to the light. I exaggerate, but at that point in my life, that was the effect of Frankie’s little note.

The author with Sionil Jose at the CCP lobby on his 90th birthday celebration.

Between 1977 and 2015, our friendship was punctuated by visits to his office and walking (when he was stronger) to Za’s Café, also known as Hizon’s Bakery, where he taught me to have my giant ensaymada toasted by the kitchen and to dunk it in hot chocolate. He would quiz me on the books I was reading or what manuscript I was working on. He advised me to get out of journalism and go full-time into writing poems and fiction (that was back when I tried my hand at short story writing). But I couldn’t find something substantial enough that would financially support such a decision. I told him, “I don’t have a Tessie Jose in my life,” a reference to his wife who ran the business side of the bookshop while he made the book selections.”

In a typewritten letter from Hawaii in the 1980s when he was on a fellowship, he wrote that one could be a slave to a job or a barkada that propped one’s ego and natural urge to have a sense of belonging. He thought that was my reason for liking too much and getting too comfortable in my then job at the Population Center Foundation’s publications group.

I also attended, although not faithfully, the Philippine Center of International PEN (Poets, Playwrights, Essayists, Novelists) conferences, usually held at the Cultural Center of the Philippines Main Gallery. Under Frankie’s watch and influence, the lunches and dinners were always lavish affairs with poetry readings serving as dessert, which prompted poet Virginia R. Moreno to complain, “Why make us sing for our supper?”

At one Southeast Asian Writers Conference in a hotel in Baguio City (since then flattened by the 1990 earthquake), Tessie took me aside and invited me to lunch at their nest. I call it a “nest” because it is the honeymoon cottage which the Jose couple rented out from the Mitra family in the latter’s compound. It wasn’t too far from Burnham Park, but it was still and quiet, perfect for visits from the Muse. She said that was where Frankie took his writing breaks, scrawling or typing on the table in the breakfast nook that featured a large picture window that looked out to the main house’s driveway and manicured garden. I was so honored to be let inside their private world.

Another similar occasion was a dinner Frankie hosted for Filipinos who had returned from Hawaii from their official fellowships, among them my colleagues at PCF, Marissa Camacho Reyes and Alejandrino Vicente. Venue was his home in Project 6, Quezon City, a two-story affair which was chock-full of arts and crafts from Southeast Asia. It seems Frankie or Tessie had a liking for all things batik, as the tablecloth and placemats were of that fabric.

He had a fully stocked bar, a feature of PEN meetings at Soli. Everyone had wine; he even brought out absinthe. Then with a straight face, he turned to me, saying, “For Babeth, give her a Shirley Temple.”

I was in my late 20s but still an initiate into the world of alcohol. Which may be why in his eyes, I would be forever a young writer. In my copy of his book To the Young Writer and Other Essays, he signed, “For Babeth Lolarga—A young writer always.”

Sionil Jose’s note to the author

It was my first time to sample Korean food prepared by one of his daughters—it may have been Jette on one of her trips home from the US. Jette died early in December last year. I think this may have contributed to her father’s weakening and demise, for she was known as his editor and right-hand person.

When the group dispersed to go their separate ways home, Frankie asked me to stay behind, for he would take me to a writers’ party, a Phase 2 to the evening. There would be drinks, he said, maybe some poetry read. But when we reached the house in Greenhills, the people were making ready to leave, except for Virgilio Almario, future National Artist, who was flushed from his nth beer. We chatted for a bit, then Frankie announced he would drive me home, a little out of the way from Project 6, but he was still strong and could manage to drive his sedan at a late hour while humming and singing along to a tape (or was his radio tuned in to DZFE?) of The King and I.

I can’t count the times Frankie took me home after an evening at Soli or dinner out in Malate. He and Tessie shushed my attempts to say I could make my way home safely by cab. My address on Sta. Clara street, Kapitolyo, Pasig, became a little familiar to him through my letters, that he used it as a location for one of his stories.

Marissa had a similar experience. She and Frankie once took a boat ride in Hawaii, originally to go sightseeing, but instead it became an occasion for her to unburden the life of her grandmother. Before she knew it, he wrote a short story molded after the narrative she shared.

Sometime during my marriage, husband Rolly Fernandez and I went on a Sionil Jose reading marathon. As I narrated in my blog brooksidebaby.blogspot.com, “It reached a point where we’d try to discuss what we had read and ended up mixing the characters and plots. Rolly counted how many times Frankie used the word ‘sybarite’ in a novel. That sounds like my husband all right. You can keep the editor at home but not the editor from NOT working.”

Frankie and Gilda Cordero Fernando in 2009 at Cafe Juanita.

Frankie wasn’t just an author. He was also an aesthete—his Solidaridad Galleries gave Onib Olmedo, Mario de Rivera, among many, their first exposure. He said that whenever an abstract artist would apply for an exhibit, he would pose for the artist first or show his fist to ensure that said artist knew his/her human figure.

Another pleasure to watch was his interaction with his confreres like the younger Gilda Cordero Fernando, who used to have her own Filipiniana corner in Frankie’s late lamented gallery and fellow nonagenarian Elmer Ordoñez, the literary critic. Because of the latter’s hearing problem, their animated discussions would turn into shouting matches. But they remained dear friends.

As the writer and wellness coach Mariel Francisco recalled, “Frankie and Gilda had this wonderful friendship in which Tessie was a vital third element, and later (at Frankie’s request)

I became the fourth. Sometimes at Gilda’s, other times at Frankie’s, they would outdo each other’s meriendas. They had the most vociferous arguments, for Gilda openly disagreed with Frankie on almost everything. And Gilda lost no opportunity to tell Frankie to his face that without Tessie he could do nothing.But beyond it all they remained close and affectionate friends!”

I remember Gilda embracing Frankie at their every encounter and saying out loud that her arms could not encompass his body because of his growing girth.

I think the secret to earning Frankie’s trust was to agree to disagree, walang personalan. It’s too late in the day to wish that the young turks of literature would have been kinder to a man who in his heart was the embodiment of kindness, a sturdy pillar of support and wisdom for us to lean on.

This article first appeared in TheDiarist.Ph