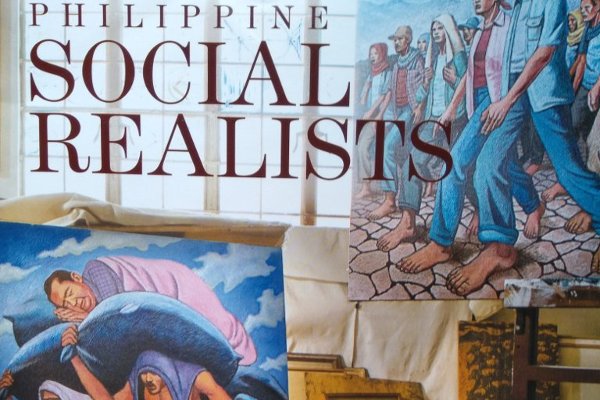

Philippine Social Realists

by Amadís Ma. Guerrero

Erehwon Artworld Corporation, 2019

The book profiles ten Filipino artists who have been doing work that reflect their critical responses and views on the sociopolitical realities of Philippine society. It focuses on their inner lives and the influences that led them to who they are today and what they do as artists.

Mostly in their 60s and 70s now, they are Nunelucio Alvarado (b. 1950), Demetrio dela Cruz (b. 1971), Antipas Delotavo (b. 1954), Pablo Baen Santos (b.1943), Edgar Talusan Fernandez (b. 1955), Renato Habulan (b. 1953), Leonilo Doloricon (b. 1957), Imelda Cajipe-Endaya (b. 1949), Karen Ocampo Flores (b. 1966), and Jose Tence Ruiz (b. 1956).

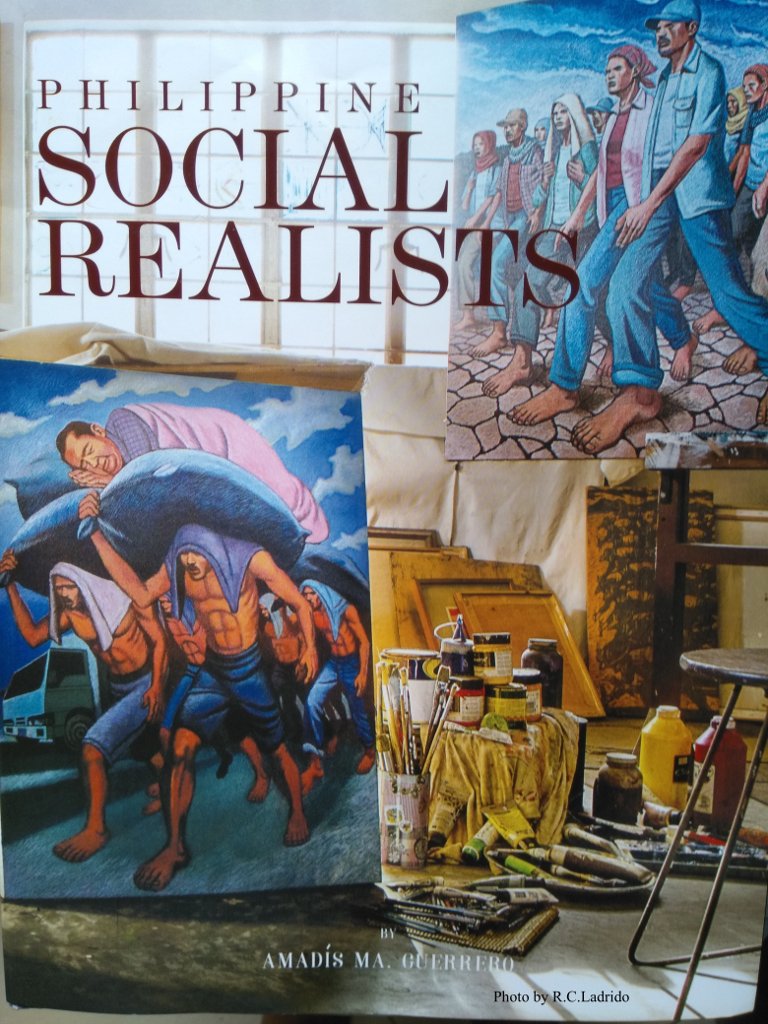

Antipas Delotavo, Diaspora, 2007. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Commonalities

Some common threads weave through the lives of these artists.

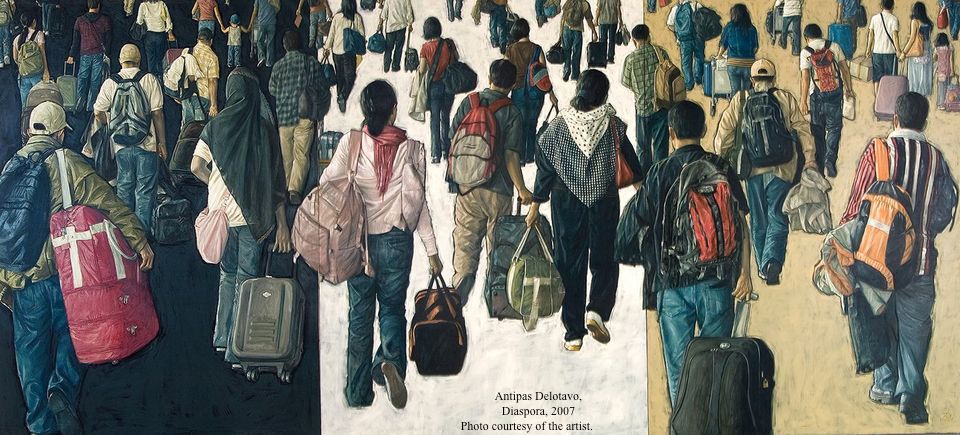

Being poor: Having a working class background, the father may be a sign painter, a janitor or street sweeper, and the mother, a market vendor. Renato Habulan, born in Sunog Apog, Tondo quips, “I was born into reality.” At a young age, Nune Alvarado has felt life’s disparity as part of the have-nots, of being dejado. For him, it was a challenge to rise above it and triumph.

The kindness of strangers: Some kind intervention made going to college possible for some of them. Gil Lopez Kabayao, the famous violinist, happened to see an early work of Nune Alvarado and made an appeal to the public to help a promising artist. Pura Kalaw Ledesma, the founder of the Art Association of the Philippines, responded and got him a one-year fine arts scholarship in UP Diliman. For Ato Habulan, his angel was Rep. Paco Reyes, a progressive legislator, who sponsored him to study fine arts at the University of the East in 1976.

Influences: Neil Doloricon immersed himself after college, in the labor movement and labor federations with a nationalist orientation. It would provide him with authentic source materials in his future artmaking. Biboy Delotavo recalls their small farm in Iloilo where he spent summers and learned how to plant rice and plow the fields with farmers. His images of ordinary Filipinos looking for a better life came from those farmers. And for Bogie Tence Ruiz, his step-grandfather showered him with art books at the age of five, introducing him to Caravaggio, Picasso, and Modigliani. He also looked up to the works of his much older cousin, Virgilio Aviado, a printmaker.

Renato Habulan, Kagampan, 1982

Martial law period: The imposition of martial law in 1972 and the Marcos regime’s grip on power led to countless protest actions and demonstrations until the overthrow of the Marcoses in 1986. It was a time of turmoil, military repression, imprisonment, torture, and killings. It was also a period of awakening and for many artists, a time of taking a stand.

And stand they did through Kaisahan (Solidarity) an art group formed in 1975. In fact, six of the artists in this book are its founding members, namely Baen Santos, Delotavo, Doloricon, Fernandez, Habulan, and Tence Ruiz.

![]()

Neil Doloricon, Lockdown, 2020

The Spirit of Our Times

In his introduction, Cid Reyes, art critic, underscored that Filipino artists have remained “as unflinching as ever in their pursuit of the truth” of the conditions of the country.

Amadís Ma. Guerrero dedicates the book to Alice G. Guillermo (1938-2018), an art historian, art critic, and academic of the University of the Philippines, Diliman, who wrote a seminal book on Philippine art, Social Realism in the Philippines (1987).

Guillermo coined the term “social realism,” an art movement that refers to works done by Kaisahan. Its paintings, murals, banners, and other works were directed against the Marcos regime and the rule of martial law. Much later, she used the term Protest/Revolutionary Art to include a wider spectrum of similar artistic practices.

Kaisahan circulated a manifesto that stated that they will develop an art that “reflects the true conditions and problems in our society” as part of its search for national identity. The manifesto was made public during their exhibit, “Truth, Relevance, Contemporary” at the Ayala Museum in December 1976.

For the 10 artists, their works that exude political intensity have certainly endured and the spirit of their times have lived on to this day. It has provided the continuing impetus for younger generations of Filipino artists to take up their own stand through visual art.

It is said that to understand art, one needs context. For social realism, Philippine society today is its own context. As Bogie Tence Ruiz aptly puts it: “If you live in a country like this, how can you not make art like this? ”