By VERA FILES

(Conclusion)

Two decades after its creation by the Constitution, the Judicial and Bar Council remains an institution critics say is riddled with “systemic deficiencies” and even defects, and is badly in need of reforms.

While some of the reforms being proposed by lawyers, judges and civil society would require amendments to the 1987 Constitution, others can be implemented with simple policy issuances, especially by the President.

Some of proposed reforms involve altering the composition of the JBC, while others have to do with improving its processes. Still others stress the need to rethink the question who could best appoint the country’s justices and judges in a transparent and competent manner and to ensure their independence.

Changing the composition

One proposal repeatedly being made is the call to limit congressional interference by returning to the practice of allotting Congress only one vote in the JBC, in keeping with the provisions of the Constitution.

In his writings, former Supreme Court Chief Justice Artemio Panganiban said, however, a proposal during his time to terminate the arrangement of having two legislators in the council, each with one vote, was eventually abandoned because of what could have become an “adversarial proceeding.”

To further depoliticize the JBC, Panganiban even proposed that the President be entitled to two representatives in the council (the justice secretary and private sector appointee); Congress also to two (a senator and a congressman); and the Supreme Court to four (the Chief Justice and the three others named by the court).

Retired Supreme Court Associate and now JBC executive committee chairman Justice Regino Hermosisima, who counts among the longest-serving regular members, once suggested further expanding the membership of the council to 12 to accommodate more representatives from the Judiciary.

Indeed, larger judicial councils have been the trend in some countries, according to a study by Judge Sandra Oxner of the Commonwealth Judicial Institute of Canada. Another study, by the International Foundation for Electoral Reforms (IFES), meanwhile, reported an emerging international consensus on a broad-based membership for the councils, to include a majority of judges elected by their peers.

But the most successful models of judicial councils, according to the IFES study, are those with representation from a combination of State and civil society actors who are given substantial powers.

Former 1986 Constitutional Commission (ConCom) member and now Elections Commissioner Rene Sarmiento suggests at least two more JBC members, to be drawn from public interest and human rights groups.

Sarmiento recalled that shortly after the EDSA People Power revolution in 1986 when the country was under a revolutionary government, members of the judiciary were recommended by a select committee, of which he was a member representing civil society. Sarmiento said the committee was successful because of active civil society members.

Regular members

The selection, appointment and reappointment of the four regular members of the JBC—representing the retired Supreme Court justices, Integrated Bar of the Philippines, private sector and legal academe—have been long-running issues because these are perceived to have made them as vulnerable to politics as members of the judiciary.

Presidential intervention in the appointment of the regular members, as well the absence of consultation, grates on the very sectors from which the regular members are drawn. Calls have been made to clip the president’s power to appoint the regular members.

The dominant question is whether to retain the setup where the president appoints their representatives or give them a free hand to make their own choices to ensure that the regular members are “truly representative” of their sector. One analyst describes it as a matter of “respecting the demarcations.”

But even proponents acknowledge this is easier said than done, and may boil down to a “slugfest” even for the most organized sector, the IBP, which they said has been wracked by infighting.

In the case of legal academe, law schools have different ways of listing faculty members, and taking a vote on who should represent the sector might end up being lopsided in favor of schools with bloated faculty rosters.

As for the private sector, reaching a consensus on who should represent it may be a complicated process, given the associations that abound.

But proponents are also quick to say that a mechanism on how to choose their representative must and can certainly be worked out by each sector, even if this would take time.

Panganiban, however, feels the President should be stripped entirely of his power to appoint the representatives of the retired justices, IBP and legal academe to strengthen “the anti-political shield of the judiciary.” The three, he said, should instead be appointed by the Supreme Court. His proposal would leave only the representative of the private sector for the President to appoint.

Altering the practice on appointments of representatives to the JBC falls within the powers and prerogative of the President. He or she may simply adopt a policy to appoint only regular members who have been named by their sector.

CA hand in JBC

Panganiban also wants an end to the practice of having all four regular members undergo confirmation by the Commission on Appointments (CA). “(T)he present system has shielded justices and judges from direct congressional interference, but not the four regular JBC members who need CA confirmation,” he said.

Restored through the 1987 Constitution, the Commission on Appointment confirms or rejects nominations submitted to it by the President and acts as a restraint on his or her vast appointing power. Although members of the Senate and the House of Representatives make up the 25-member body, the CA is theoretically independent of Congress because it derives its powers directly from the Constitution. In practice, though, the majority of CA members may belong to the political party of the President.

Other court observers do not share Panganiban’s view. They say what is needed is for the CA to play a more focal role and rigorously screen nominations to the JBC, beyond the perfunctory and cursory look. And what is needed on the part of judicial watchdogs, especially those from civil society, is to monitor CA proceedings on the nominations of the council’s regular members as closely as they watch nominations to the High Court.

Back in 1986, Fr. Joaquin Bernas had explained to fellow ConCom members the reasons for making regular JBC members go through the CA wringer: “The requirement of confirmation by the Commission on Appointments, which I understand is provided in the proposal for the legislature, will have the effect of a check on the discretion of the President in the appointments of the Council. “

Term limits for regular members

While there is disagreement over who should be named to the JBC and how they should be picked and screened, members and monitors of the judiciary alike agree on one thing: the need to impose a term limit on the regular members. The Constitution imposes no limit on how many times a regular member can be given a four-year term.

Immediately upon their appointment or reappointment, some JBC members are said to begin lobbying hard with the Palace, politicians and other stakeholders to ensure they clinch another term. They end up owing the President and those who helped him a debt of gratitude and, at times, are forced to do their bidding. Other reappointees, according to a JBC member, develop “bad habits,” like socializing with applicants.

Sarmiento acknowledges that the framers of the Constitution were so focused on restricting the terms for politicians, they overlooked term limits for the JBC members. “We were of the belief that since JBC regular members would not be politicians, there would be no need for term limits,” he said.

Sarmiento and many in and out of the judiciary and the legal profession believe a single four-year term for JBC regular members is enough for members to learn the ropes and guarantee their independence and accountability.

The IFES study also recommends an additional measure: The term of council members should not coincide with that of the appointing authority.

As for the “bad habits” that some regular members reportedly develop while in office, Panganiban said the regular members should also strictly observe the judicial code of ethics. “As the full-time vanguards of the judiciary—(they) should, like judges, perform their work with same standard of ‘proven competence, integrity, probity and independence,’” he said.

Limiting the terms of regular members can be done through only a policy issuance discontinuing the practice of reappointments. The Commission on Appointments, on the other hand, can agree as a matter of policy not to confirm reappointments.

Policy issuances are, of course, subject to changes of leadership in both the executive and legislative branches. But they could set precedents that may lead to something more permanent, including legislation and even changes in the Constitution.

JBC processes

As a vetting agency, the JBC plays a crucial role in preventing the unqualified from getting appointed to the bench. It is thus imperative for the council to adopt and implement rules that ensure applicants for vacancies in the court meet the criteria stipulated in the Constitution and by the Supreme Court.

Having closely observed the judicial appointment process and engaged the JBC over the years, members of civil society groups like Bantay Katarungan and SCAW are in a good position to identify areas of reform in the way the council operates. Officially, SCAW has written the JBC to propose the following:

Use of a score sheet. Instead of the current system where the JBC votes for and ranks candidates, the score sheet would evaluate candidates on the constitutionally mandated criteria and the rules of the JBC to ensure that only those who meet a predetermined minimum score would be shortlisted.

Live media coverage. Allowing live media coverage would widen the audience for the JBC’s public interviews. It would not only “demystify” the JBC process but also contribute to raising the level of public discussion on the appointment process.

Access to information. SCAW has batted for a policy that favors access to information, and clearly and narrowly defines the exceptions to access. “With such a policy in place, the JBC can unburden itself of dealing with mundane and routine information requests, and thus make more efficient use of its time,” it said.

Predictability and regularity in setting key dates in the selection process. Saying the retirement dates of justices of the Supreme Court and of the Ombudsman are, like the constellations, known in advance, the consortium has proposed a uniform timetable for the screening process, such as outlining the number of days before a scheduled retirement that nominations would open.

Minimizing the influence of the Supreme Court. SCAW has asked JBC to delete Rule 8, Section 1 that gives “due weight and regard” to recommendees of the Supreme Court. The rule requires the JBC to submit to the Supreme Court a list of the candidates for any vacancy in the court with an executive summary of its evaluation and assessment of each of them and relevant records concerning the candidates “from whom the court may base the selection of its recommendees.”

The JBC has also been asked to actively search for nominees, instead of limiting itself to those who apply as it does at present, a task it can do in collaboration with civil society. But an even better process, according to the 2008/2009 Philippine Human Development Report, is for the JBC to do away completely with recommendations it gets from politicians and other interest groups, and instead rely on an independent and diligent search mechanism for qualified candidates.

The Bantay Korte Suprema (BKS), a coalition of individuals and groups that monitored Arroyo’s appointments to the High Court, had previously suggested that the council seek the help of the Civil Service Commission in checking the background of applicants. It found the investigations done by the National of Bureau Investigation inadequate.

Just as importantly, the BKS had asked JBC members to explain their votes to the public to generate discussion on the candidates and make known the reasons behind the appointments.

And to assert its independence, the JBC has been urged to spurn Malacanang’s request to submit a second shortlist should the President’s nominee not appear on the first list transmitted to the Palace.

The appointing power

Court observers say other options should be explored to guarantee the independence of the court, especially from the executive branch.

Bernas has argued for a return to the 1935 system that requires appointees to pass through the CA, at least for candidates to the Supreme Court and the Court of Appeals. He agrees with the late former senator and fellow ConCom member Francisco Rodrigo who favored the CA choosing pre-martial justices. Bernas recalls how Rodrigo “valiantly” fought, but failed, to restore the 1935 constitutional provision.

“From President Quezon on to Osmeña, Roxas, Quirino, Magsaysay, Garcia, Macapagal and even Marcos before he declared martial law, the appointments to the Judiciary, especially to the Supreme Court and to the Court of Appeals, were high-class, so much so that we had the highest, the utmost respect for the Judiciary,” Rodrigo had said. “Before the declaration of martial law, we regarded the Supreme Court, up to the Concepcion Court, with awe and respect. And so why should we change this now, merely because of what happened during martial law?”

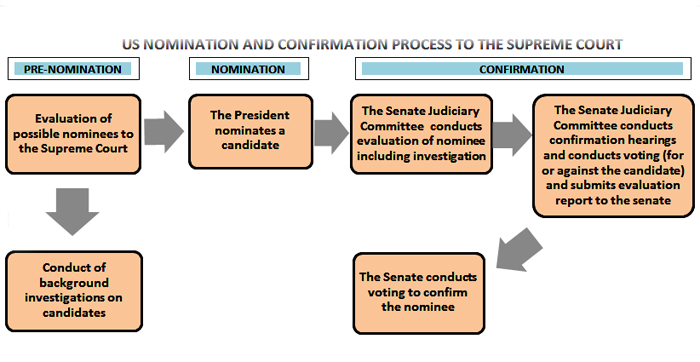

In the end, the Commission on Appointments’ greater openness in conducting public hearings and disclosing information and documents is said to be a more transparent process than the JBC. It would be just like the US Senate Justice Committee which confirms appointments made by the American president to its Supreme Court, court observers say.

But political pundits say the U.S. system works because of a strong two-party system that provides checks and balances. Post-martial law politics in the Philippines, on the other hand, has been characterized by a weak party system.

Other proposals on the appointments of judges and justices range from retaining the President’s appointive power but with modifications, to transferring the power entirely to the Supreme Court. Some of the proposals that modify the President’s power to appoint include:

- Enacting a law transferring the President’s power to appoint members of the lower courts to the Supreme Court, but let the President continue appointing justices to the Court of Appeals and Supreme Court.

- Amending the constitution to empower the JBC to confirm and veto the appointments, so that it takes on a role akin to the CA in the pre-martial years. This is expected to depoliticize appointments as the JBC is, unlike the CA, supposed to be a nonpolitical body.

- Amending the constitution to require the JBC to submit only one name to the President like what the select committee did during the revolutionary government days in 1986, since the President can always give back the list.

A radical proposal would transfer the President’s power to appoint members of the judiciary to the Supreme Court sitting en banc.

There is no telling how far the proposed changes to the JBC will go, but there is one thing almost certain about calls to reduce the President’s appointing power. No Philippine President would easily give up the powers that make him one of the most powerful presidents in the world.

(This series is adapted from VERA Files’ study on the post-Marcos judicial appointment process. VERA Files is put out by veteran journalists taking a deeper look at current issues. Vera is Latin for “true.”)