By NORMAN SISON

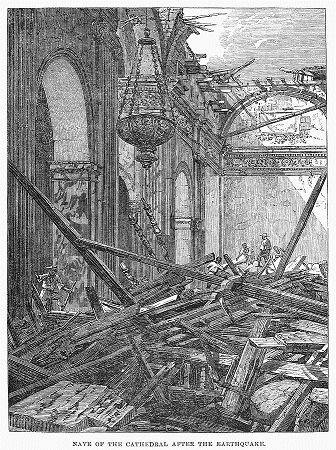

ON the second day of his memorable visit to the Philippines, Pope Francis celebrated mass for the local clergy at the Manila Cathedral. In his welcome remarks after the ceremony, Cardinal Luis Antonio Tagle, the Archbishop of Manila, related to the Pope how the cathedral was repeatedly destroyed by fire, earthquakes and one war throughout its 440-year history.

Most Filipinos know that the church was gutted in World War II, when American troops rooted out the Japanese in the 1945 Battle of Manila. But almost buried in the history was a Catholic priest, Pedro Pelaez, who was among those who perished when the church collapsed during a strong earthquake in 1863.

Among the Philippines’ pantheon of heroes and historical figures, Pelaez is nearly a footnote to Filipinos. But his place in Philippine history is no less significant.

The story of Pelaez, whose efforts marked the beginning of the Filipino nationalist consciousness, provides an ironic backdrop to Pope Francis’s visit who is seeking reforms within the Roman Catholic Church.

Pelaez was born in Pagsanjan, Laguna Province, on June 29, 1812, to a Spanish official, Jose Pelaez, and to Josefa Sebastian. Pelaez took up studies at Colegio de San Juan de Letran, earning a degree in Bachelor of Arts. He then went to the University of Santo Tomas to study for the priesthood.

Pelaez was ordained in 1833 and served at the Manila Cathedral. A brilliant theologian, he rose to the rank of vicar capitular or ecclesiastical governor of the Manila Archdiocese.

Pelaez protested the decrees that barred native-born clergymen from serving as parish priests and limited them to assisting Spanish curates. He argued that it contradicted the Christian principle of equality under God.

To the Spanish colonial authorities, the reforms sought by Pelaez were already considered earth-shaking. Mexican and other Latin American clergymen played an active role in the independence movements against Spanish colonial rule.

Fearing a repeat in the Philippines, in 1826, Spanish king Ferdinand VII removed the Filipino priests from their parishes. The colonial authorities reasoned that Filipinos — as Spaniards born in the Philippines were called — might be of divided loyalties and, therefore, could not be trusted.

The Filipinos protested the discrimination — and that crystallized the nationalist consciousness.

“Many Spanish clergymen born in the Philippines shared this faint nationalist feeling — just as Englishmen born in the American colonies began to regard themselves as Americans in reaction against British oppression — and they initially directed the struggle against the monastic orders,” wrote the late American journalist Stanley Karnow, in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book, In Our Image: America’s Empire in the Philippines.

At about 7 p.m. on June 3, 1863, while worshippers were singing their vespers celebrating Corpus Christi, a massive earthquake demolished the Manila Cathedral. Pelaez and several worshippers were killed.

The Spanish friars attributed his death to an act of divine providence. But that would not be the end of it.

Pelaez had worked with another dissident cleric at the cathedral, Mariano Gomez. That sentiment would send Gomez to his death by garrote nine years later along with two other clergymen, Jose Burgos and Jacinto Zamora. Their deaths are commemorated by Filipinos today in an acronym — Gomburza.

However, it was Burgos who caught the attention of the authorities for his liberal views.

Burgos was born in Vigan, Ilocos Sur Province, on February 9, 1837 to a Spanish army officer. On the eve of his ordination in 1864, Burgos denounced the friars for labelling the native-born clergymen as unfit for the priesthood. He argued that “preeminence stems from education rather than any innate superiority” and blamed the friars for keeping the natives in “ignorance and rusticity.”

Burgos was charged with sedition along with Gomez and Zamora for allegedly instigating a mutiny of Philippine-born Spanish troops. After a railroaded trial, they were executed at the Luneta promenade — present-day Rizal Park — on February 17, 1872.

Among the crowd who witnessed the executions was Paciano Rizal, a friend of Burgos. Paciano had brought with him his younger brother, the future national hero Jose Rizal, then aged 10. The executions, Rizal wrote, “awakened my imagination, and I vowed to devote myself to avenge such victims some day.”

In 1891, Rizal dedicated his second of two nationalist novels, El Filibusterismo, to the memory of the three priests. Five years later, on December 30, 1896, Rizal was executed at the Luneta for allegedly masterminding the Philippine Revolution, which had broken out earlier that year. The revolt took its inspiration from Rizal and the Gomburza martyrs, among others.

The issues facing the Catholic Church have changed since Pelaez’s death — all except one, however — that of the church finding itself needing to keep in step with the times.