Former President

Gloria Macapagal Arroyo has dismissed concerns about the Philippines’

mounting loans from China, saying they are not a “debt trap.”

Speaking at the

Belt and Road China-Philippines Forum on People-to-People Exchange &

Economic Cooperation on July 26 at the Sofitel Hotel, Arroyo said,

“As long as we can serve the interests, it’s not a debt trap.”

Arroyo’s views

are similar to what Chinese embassy’s deputy chief of mission Tan

Qingsheng said in a speech at the same forum. “All the cooperation

projects are not ‘imposed on anyone’ or designed to ‘frame’

any other country. The so called ‘China debt trap’ is completely

groundless. The BRI (Belt and Road Initiative) is a ‘pie’ for

everyone to share, not a ‘pitfall’ that hinders development,”

he said.

Arroyo asked:

“How come when we borrow from America and from Japan, they don’t

call it a debt trap? The most important thing is the ratio of our

debt to our GDP (Gross Domestic Product).”

Under her

presidency (20 January 2001 – 30 June 2010), Arroyo was able to

service 9.6 per cent of the country’s debt. Debt service,

according to the Philippine Statistics Authority, is the sum of loan

repayments, interest payments, commitment fees, and other charges on

foreign and domestic borrowings.

According to the

latest figures from the Department of Finance, the country’s

debt-to-GDP ratio increased from 42.6 percent in March 2018 to P44

percent in end-March 2019. The debt-to-GDP ratio is an indicator of

the ability of a country to pay its debts; the lower the figure, the

better.

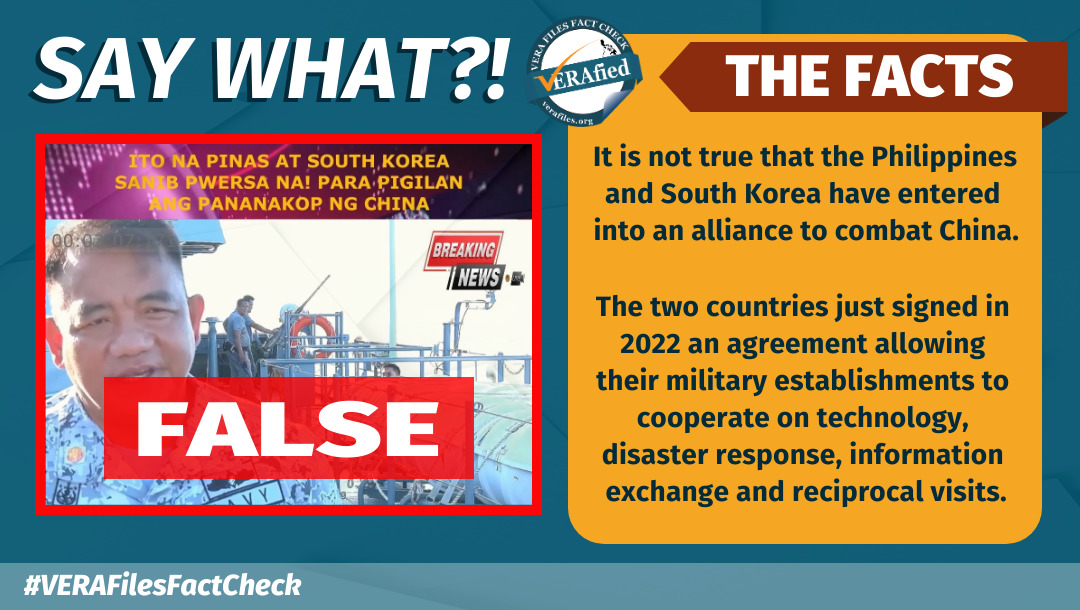

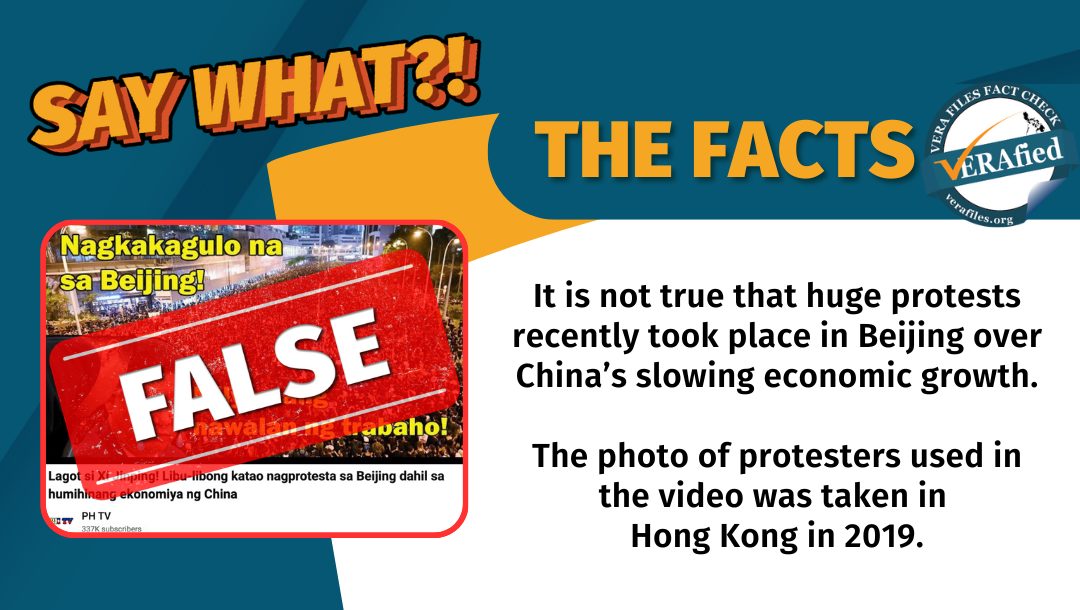

China has been

criticized for engaging in debt trap diplomacy, in which a country

extends excessive credit to another country with the intention of

extracting economic or political concessions when the latter becomes

unable to honor debt obligations.

Unveiled in 2013,

China’s BRI is an ambitious global development strategy involving

infrastructure development and investments in 152 countries and

international organizations in Asia, Europe, Africa, the Middle East,

and the Americas.

Tan said the BRI

is not a geopolitical tool, but a “peaceful development platform.”

In March, Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez III gave assurances that

the country will not fall into a debt trap. The Philippines, as of

end of 2018, has nearly $980 million worth of loans from China. He

said that no government projects funded through Official Development

Assistance allow the takeover or appropriation of domestic assets.

Critics have

questioned some projects under the BRI. Members of the Makabayan Bloc

urged the Supreme Court to stop the implementation of the

US$62-million Chico River Pump Irrigation Project loan from the

Export-Import Bank of China for being “onerous.” The government

defended the project, saying it has gone through a lot of reviews and

is not violative of the Constitution.

In recent years,

China’s BRI, which includes investments in infrastructures, has

faced scrutiny. In 2017, it was reported that the Sri Lankan

government agreed to lease its Hambantota Port to a Chinese firm

after it failed to pay its debts to China.

According to the

Center for Strategic and International Studies, China’s BRI-related

credit has a high impact on the debt-to-GDP ratio of countries

availing of its loans. CSIS said countries such as Djibouti,

Kyrgyzstan, Laos, the Maldives, Mongolia, Montenegro, Pakistan, and

Tajikistan are “at a high risk of debt distress” due to their BRI

obligations.