Public office has long become a family business in many parts of the Philippines. Powerful clans play a major role in electoral exercises, from the national down to the barangay level, either as candidates or financial backers.

While there are indeed good and bad political dynasties, it is in the hands of the people to keep the good ones and give others a chance to prove their worth as their next leaders.

Participation in the elections, no matter how “dirty” the campaign may be, is an exercise of responsible citizenship. Casting a vote is a right guaranteed under the Constitution, so we better use it well by choosing the best among the candidates.

Three instruments embody the right of suffrage: the 1987 Constitution, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

These documents do not limit the right to vote to national positions only. These do not impose literacy or property requirements.

In Article V of the Constitution, all citizens of the Philippines not otherwise disqualified by law, who are at least 18 years old and have resided in the country for at least one year or in the place where they propose to vote for at least six months immediately preceding election day, have the right to vote.

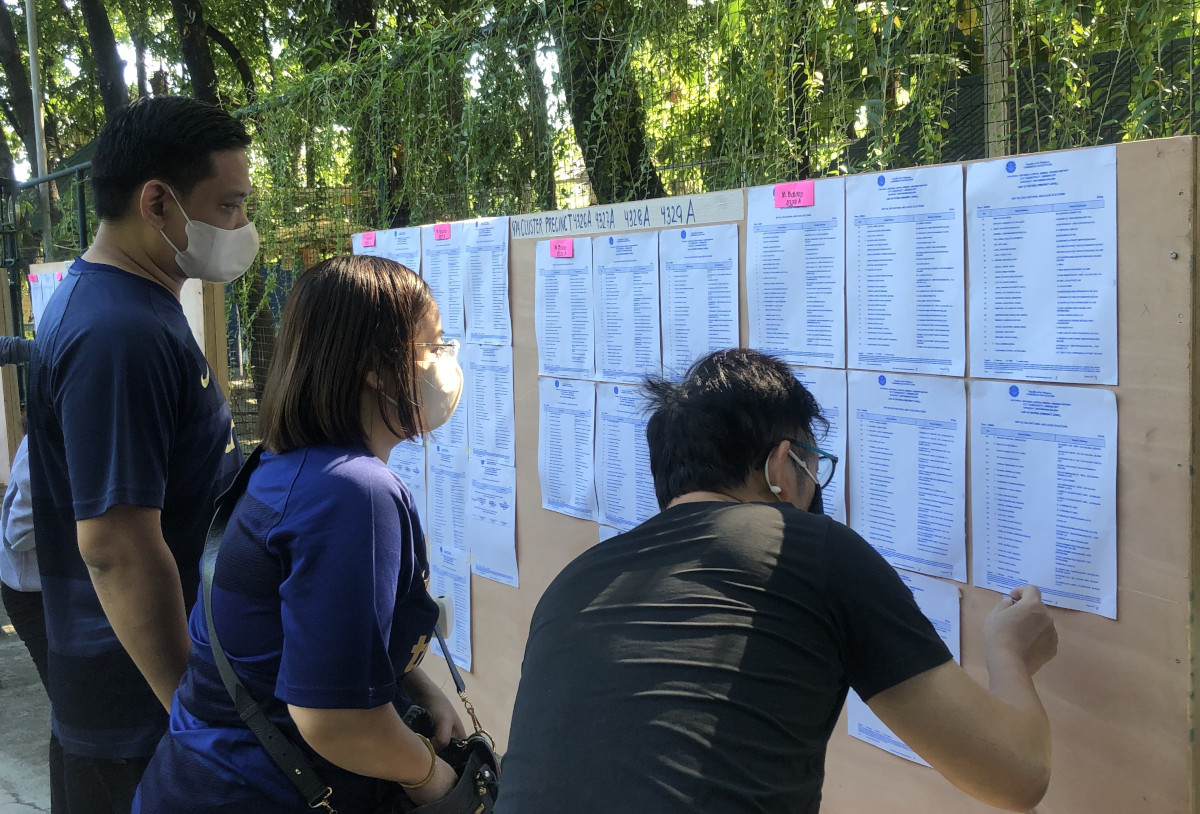

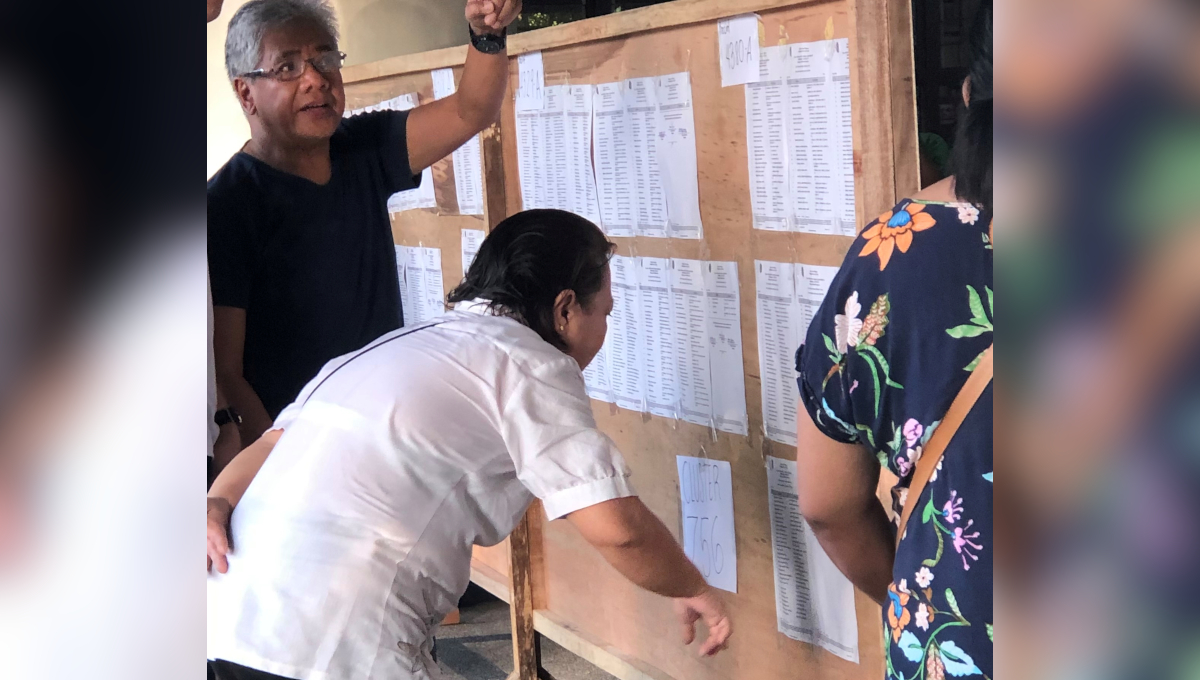

The upcoming Barangay and Sangguniang Kabataan Elections (BSKE) present yet another opportunity for voters to choose their leaders in the country’s smallest unit of government.

The BSKE is supposed to be non-partisan. SK candidates are not supposed to have any parent, grandparent, sibling, or spouse occupying an elected position.

Section 10 of Republic Act 10742, or the “Sangguniang Kabataan Act of 2015,” mandates that SK candidates “must not be related within the second civil degree of consanguinity or affinity to any incumbent elected national official or to any incumbent elected regional, provincial, city, municipal or barangay official, in the locality where he or she seeks to be elected.”

This was one of the electoral reforms intended to insulate the SK system from political dynasties as intended under Section 26 of the Constitution.

In past elections, we have seen political clans fielding younger members of their families as SK candidates even before finishing their studies, grooming them early for higher positions.

So as not to defeat the intent of the SK reform law and the non-partisan nature of the upcoming elections, we should be wary of candidates enjoying clandestine support from politicians and political parties.

The Commission on Elections reported a “blockbuster” turnout of aspirants who filed their certificates of candidacy for the Oct. 30 BSKE. From Aug. 28 to Sept. 2, the poll body recorded more than 1.4 million hopefuls (nearly 97,000 for barangay chairman and over 730,000 for barangay council, 92,000 for SK chairman, and 493,000 for SK council) to fill in 672,016 positions in the country’s 42,001 barangay.

Big names in politics may not be running as candidates for the barangay elections, but they do invest in community leaders who can mobilize grassroots support for their future electoral adventures. There is no anti-dynastic prohibition for candidates for barangay chairman and council members who belong to political families.

As of Aug. 28, the Legal Network for Truthful Elections (Lente) said it had monitored abuse of state resources in some areas across the country, such as incidences of distribution of social services in one of the cities in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, with incumbent barangay officials seeking reelection providing temporary shelters to their constituents.

In other areas, student-beneficiaries of scholarship grants were required to present their voter’s ID. Barangay-based projects such as Oplan Libreng Tuli, free X-ray and HIV testing were spearheaded by LGUs, highlighting their supported candidates for the upcoming BSKE. Lente said these may constitute unlawful intervention, if not a violation of civil service rules, on the part of the local government officials who are not supposed to engage in any partisan political activities.

Candidates benefiting from these unwarranted and potentially unlawful activities must be rejected.

In casting our vote, we should bear in mind that barangay leaders are supposed to represent the people to bring about much-needed changes in grassroots communities, not as extensions of political clans, especially in areas where political patronage and corruption thrive.

An Ateneo School of Government study published four years ago noted that from 1988 to 2019, political dynasties grew by about 1% or 170 positions per election period.

“Fat” political dynasties — where members simultaneously hold elective posts — now occupy 29% of local posts, up from only 19% in 1988. They hold 80% of the country’s gubernatorial posts, compared to only 57% in 2004. In Congress, they control 67% of seats from 48% in 2004, it said.

Political dynasties not only limit political competition. Often, they exacerbate corruption, poverty and abuse of power.

If you want to reform the country’s political system and promote good governance, the barangay would be a good place to start. Vote wisely on Oct. 30. Let’s vote for candidates not because they are relatives or friends. Choose those who can be responsible leaders for everybody.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.

This column also appeared in The Manila Times.