By YVONNE T. CHUA

WHEN classes open on Monday, the country is finally giving up the distinction of being the only country in Asia that has a pre-university education of just 10 years.

The Department of Education is rolling out in all 45,619 public elementary and high schools the “K to 12 curriculum,” beginning with Grades and 1 and 7, also called the “new high school.” The 13,295 private schools have been given time to make the transition.

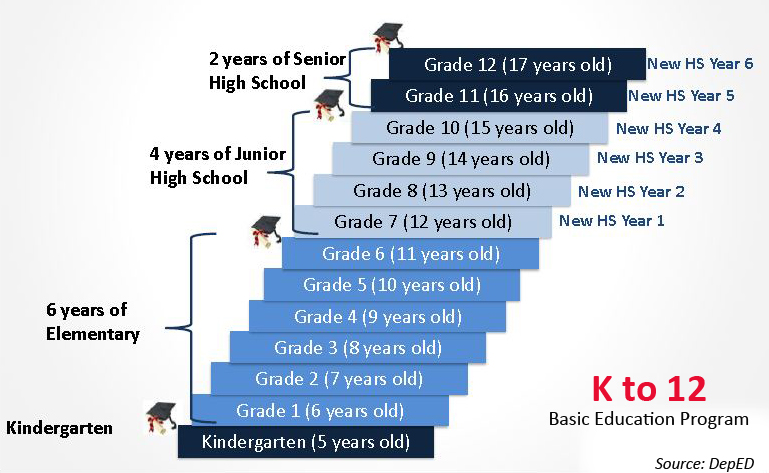

The new curriculum, now aligned with the global 12-year standard for basic education, consists of kindergarten for 5-year-olds, six elementary grades (from 6 to 11 years old), four years of junior high school (from 12 to 15 years old) and two years of senior high (from 16 to 17 years old) in what has been fashioned as a blended career and college preparatory program.

It puts an end to the six-year elementary and four-year high school education that has been in existence since after the second world war. The shortest cycle in basic education in the region, this system has been found to work against high school graduates looking for work or going to college.

The K to 12 curriculum also fulfils President Benigno Aquino III’s campaign promise to put in place a 12-year basic education in the public school system under his watch. He once said, “Those who can afford pay up to 14 years of schooling before university. Thus, their children are getting into the best universities and the best jobs after graduation. I want at least 12 years for our public school children to give them an even chance at succeeding.”

Education Secretary Armin Luistro said the enhanced curriculum will help the country “catch up with the rest of the world.”

He cited studies that ranked the Philippines fifth in overall quality of education, and eighth in quality of science and math education and capacity for innovation among the 10 countries of Southeast Asia. The country placed a poor 75th in the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report for 2011.

The lackluster performance of the country’s 22 million elementary and high school students compared to their counterparts elsewhere in the world has been blamed in part on a short pre-university education that has resulted in a congested curriculum, especially in mathematics, languages and sciences at the elementary level.

Educators acknowledge the disadvantages of students who finish high school at a young age—15 or 16 under the old curriculum. Those who opt not to go to college are too young to enter the labor force or, if they do, can end up being exploited at work. They are also too young to legally enter into contracts and start their own businesses.

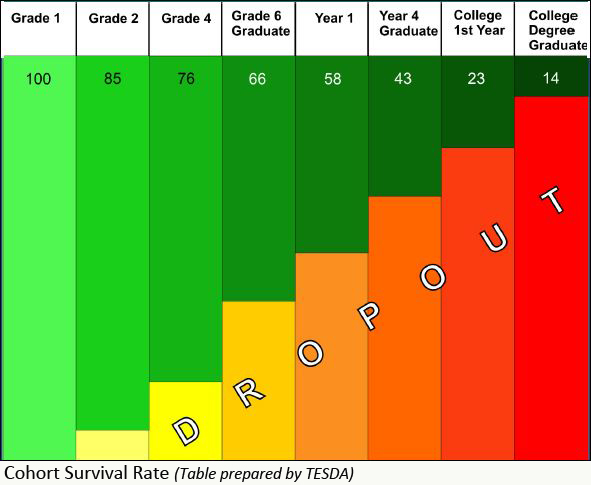

The number of school leavers after high school in the country has been high. Of those who enter Grade 1, only 23 percent enter colleges and universities and 10 percent vocational-technical institutes a decade later.

But because they haven’t mastered the basics, a number of them have had to take remedial and high school level classes in colleges and universities, according to the Commission on Higher Education. Only 14 percent get to finish college.

Today, one of the country’s biggest concerns is that those who finish college but had only 10 years in basic education may not be recognized as professionals abroad.

The Washington Accord, an international accreditation agreement for professional engineering academic degrees, prescribes 12 years of basic education as entry to recognition of engineering professionals. The Bologna Accord, meanwhile, requires 12 years of basic education for university admission and practice of profession in European countries.

Under the K to 12 curriculum, the elementary grades will focus on the core learning areas—languages, math, science and social studies.

Science will be introduced as a subject only starting Grade 3, but will be integrated in other learning areas in the earlier grades. The subject Edukasyong Pantahanan at Pangkabuhayan will be taught starting Grade 4.

One of the highlights of the K to 12 curriculum is the use of eight major languages in the country to teach pupils kindergarten to Grade 3 starting this schoolyear. DepEd adopted the “Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education” after pilot tests showed students learn better when the language used at home is also used in the classroom.

The eight languages: Tagalog, Kapampangan, Pangasinense, Iloko, Bikol, Cebuano, Hiligaynon, Waray, Tausug, Maguindanaoan, Maranao and Chabacano.

The new junior high school curriculum, which begins with Grade 7, will give students a chance to choose from the Technology and Livelihood Education (TLE) subjects–Agri-Fishery, Industrial Arts, Home Economics, and Information and Communication Technology–to be offered on top of the required subjects in the core learning areas.

By Schoolyear 2016-2017, when the current batch of seventh graders reach Grade 11 or the first of the two-year senior high school, they will focus on science, math, English and contemporary issues, plus choose their area of specialization: academics, vocational-technical or sports and arts.

The education department has identified K to 12 model schools in every region where senior high school, including the specialization tracks, will be introduced ahead of the nationwide implementation.

When the first batch of high school students under the new curriculum graduates by 2018, they should be not only functionally literate but also equipped with what DepEd calls “21st century core skills”–digital age literacy, inventive thinking, effective communication and high productivity). These, it said, would make them ready for both career, either employment or entrepreneurship, and for higher education, either in vocational-technical institutes or in colleges and universities.

To be sure, the K to 12 curriculum has other implications on colleges and universities. Only a handful will be enrolling in tertiary education in Schoolyears 2016-17 and 2017-2018 because 16- and 17-year-olds will be in senior high school instead of graduating from high school. The enrollment gap will affect finances of colleges and universities.

At present, CHEd is developing college readiness standards and revising the General Education curriculum in keeping with the new basic education curriculum. It will soon be revising the curricula in the various programs and foresees the need to shorten them.

But government is banking on the longer basic education to eventually contribute to economic growth.

Studies show that an additional year of schooling increases earnings by 7.5 percent. They also show that improvements in the quality of education will increase the gross domestic product by as much as 2 percent.