There is very little to celebrate as we observe our 123rd Independence Day.

In fact, there is more horror and irony in our contemporary life than we care to admit.

A former supreme court justice is fighting for our rights in the West Philippine Sea while a sitting president speaks of the countless benefits of remaining friends with the People’s Republic of China.

This even as scores of Filipino fishermen were rendered jobless by Chinese intrusion into Philippine seas.

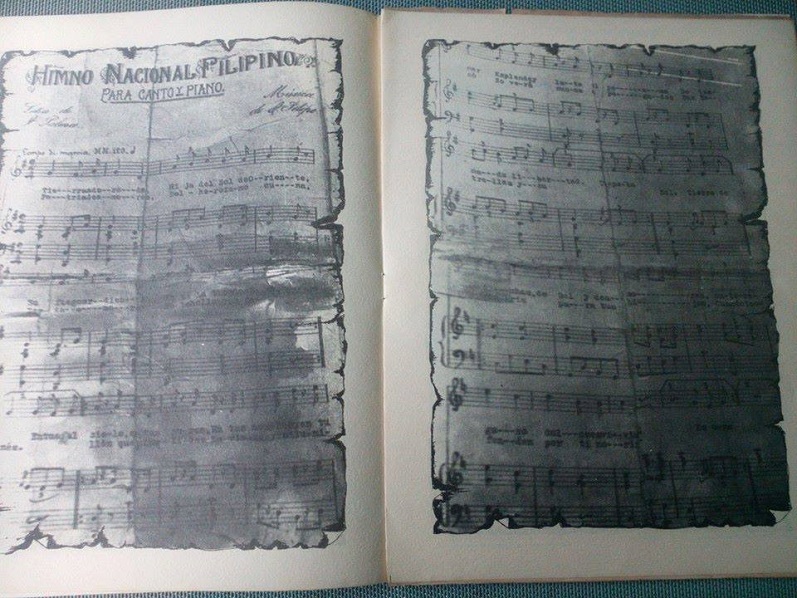

The height of treason was when Palace spokesperson Harry Roque declared Julian Felipe Reef as part of Chinese territory. He didn’t pause to ask himself why it was named after the composer of national anthem, Julian Felipe.

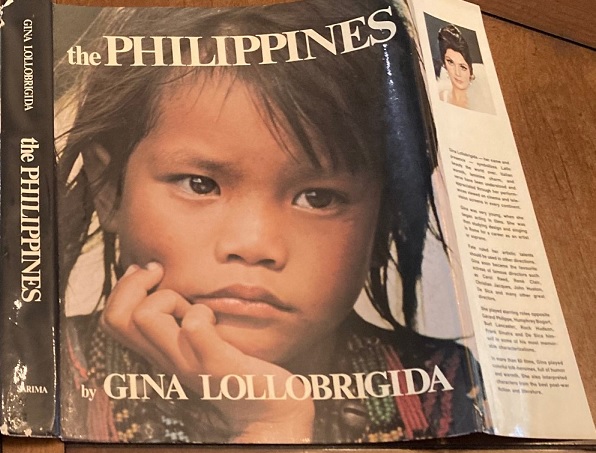

Julian Felipe Reef is named after the composer of the Philippine National Anthem

Other scenarios in our contemporary life speak of blind idolatry.

A National Artist for Literature came in defense of a living tyrant who rendered more than 11,000 people jobless during the pandemic.

It may be recalled that National Artists get P100,000 monthly stipends from people’s taxes. There must be a way of recalling awards for people who rightly deserve to be called National Artist for Perdition.

And here comes another update from the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) which is supposed to protect national heritage sites.

While no one was looking, the 89-year Manila Metropolitan Theater has been renamed the NCCA Metropolitan Theater without official statement from the National Historical Commission why it has to carry a new name which has nothing to do with history.

For one, Section 22 of Republic Act No. 10066 prohibits renaming of national cultural treasures or important cultural property by local or national legislation without the approval of the National Historical Commission.

It applies to the Manila Metropolitan Theater as it was declared a national cultural treasure (NCT) since 2010.

That’s tantamount to ignoring its past history in favor of a government agency who oversaw its renovation.

In the light of recent developments, observance of the 123rd Independence Day — with flag-raising, speeches, and virtual parades – will all come to nothing.

If at all, you see National Artist as villains and government agencies as defilers of national landmarks.

In this light, we take note of a special tribute to composer Julio Nakpil whose 154th birth anniversary was observed with a performance of his works at the Casa San Miguel in San Antonio, Zambales.

Clearly, Nakpil epitomizes the artist as hero.

While he was into music, he was also aware of what’s happening to his country.

When the Philippine Revolution started in August 1896, Nakpil heeded the call of duty to free his countrymen from the Spanish colonizers.

Under the alias J. Giliw, he served as secretary of command under Andres Bonifacio. Together with Isidro Francisco, he commanded the revolutionaries north of Manila when Bonifacio left for Cavite in December 1896.

After hostilities ceased, Nakpil fell in love and married Gregoria de Jesus, Bonifacio’s widow with whom he has eight children.

Nakpil epitomized the artist who loves his country to the core.

(Writer Carmen Guerrero Nakpil was married to architect and city planner Angel Nakpil, cousin of composer and patriot Juan Nakpil who is the son of Gregoria de Jesus, formerly married to Andres Bonifacio.)

Writer Carmen Guerrero Nakpil with President Ramon Magsaysay

In this light, the book of Mrs. Nakpil – “Heroes and Villains” — gives us a ringside view of history totally dissociated from the point of view of the colonizers.

Did Magellan actually discover the Philippines?

Nakpil delivers the cold, hard facts: “It was the people of our archipelago who discovered Magellan and the Europeans in 1521, not the other way around, as most Filipinos were taught by our grade school textbooks.”

The Philippines got its name from Spain’s King Philips II. What was he like and what was his place in history?

“In his youth, he was described as ‘slender, elegant and good-looking.’ After all, he was the grandson of the smashingly handsome Philip I, a.k.a. Felipe El Hermoso, who was so gorgeous that when he died suddenly at age 28, the besotted Queen, Juana, went out of her mind and was forever called ‘Juana la Loca.’ Historians like to say that she refused to have his cadaver taken from her bedside and kept him there unburied ‘for years.’ A side story to this royal insanity says that when Magellan baptized Humabon’s wife in Cebu in 1521,he gave the ‘Queen of Cebu’ the name ‘Juana’ in honor of the unfortunate grandmother of Philip II, Juana La Loca, a.k.a. in English history as Joanna the Mad. Fortunately, the Cebuanos did not know that little detail of their brief alliance with Magellan, or they might have planned the massacre earlier,” Nakpil wrote.

The secret delight of this book is that history is told in the context of present-day Filipinos still misled by the official chroniclers of history.

After reading the book, you begin to see who are the real heroes of history and those who can be rightfully called the villains.

Further, the book allows us to take a serious look at our mentors (the Spaniards, the Americans and the Japanese) for what they are.

She adds details of Spain’s little known past: “It had a small nobility of peasants, usurers, mercantilists and a huge mass of beggars, vagabonds, bandits and slaves. In Madrid civil servants, captains without companies, soldiers of fortune, adventurers fleeing creditors, all sought passage to the newly charted “Indies” (including Filipinas) hoping to attain, wealth, respectability and a rich wife. (See Braudel, The Mediterranean and the Age of Philip II.) These were the worthies who came to this archipelago to lord it over us.”

The author’s coup de grace: “Our ancestors were not pygmies, the naked savages with frizzy hair, as many of us were carefully taught in our foreign-guided schoolrooms by our brainwashed elders. We were one people, of the Malay race, recognized by India, China, Japan and later Arabia as their ancient chronicles attest, possessors of this land for many centuries. They had come between 200 B.C. and 300 A.D. from the vast mainland of Central Asia, from places like Nepal and Johore, in their own boats for they were excellent seafarers. They lived in organized communities, fiefdoms and villages called barangay (the name for their boats and still that of our smallest municipal unit). They were warriors, farmers, craftsmen, traders, exporters (Mindoro exported cotton to Malacca in the 10th century), investors in Moluccan enterprises. (H. de la Costa, Readings in Philippine History, and W.H. Scott, Barangay.) When Magellan landed in Homonhon in 1521,in the company of his starving, smelly, bearded white crew who had emerged from their tiny creaking, wooden caravelles, they were quickly offered jars of palm wine, welcomed to bamboo palaces and fed roast pork and gravy, rice and coconuts, amid gong music and maidens wearing shiny silk gowns and makeup and attendants wearing heavy gold necklaces, bracelets and anklets. Magellan had to warn his men against showing too much awe of the wealth, the beauty and the generosity of those early Filipinos. It’s important to remember this scene (from Pigafetta, Magellan’s publicist) because that’s where we’re from.”

There is a lot to enjoy in Nakpil’s book and readers will find out why as they go through its 118-page sojourn into history.

It is an enjoyable mirror on which we can see the ironies of our chaotic national life and the tragedy of one national artist celebrating a national villain.