On a Tuesday morning, the world woke up to the news that the Italian actress Gina Lollobrigida died in a clinic in Rome, Monday, January 16.

She was 95.

Also described as “the most beautiful woman in the world,” she is associated with such films as Beat the Devil, the Hunchback of Notre Dame and Crossed Swords.

Her leading men included such Hollywood icons as Humphrey Bogart, Frank Sinatra, Rock Hudson and Errol Flynn, among others.

Known the world over as La Lollo, she was one of the last icons of the Hollywood glory days of film.

Bogart was quoted to have said Lollobrigida “made Marilyn Monroe look like Shirley Temple.”

Her supposed rival, the great Sophia Loren, was “shocked and saddened” by her demise.

Italy’s Culture Minister Gennaro Sangiuliano wrote on Twitter: “Farewell to a diva of the silver screen, protagonist of more than half a century of Italian cinema history. Her charm will remain eternal.”

She appeared with Rock Hudson in the film Come September where she was nominated for the Golden Globe awards.

Her appearance in The World’s Most Beautiful Woman (also known as Beautiful But Dangerous, 1955) got her the first David di Donatello for Best Actress award. In this 1955 film, she interpreted Italian soprano Lina Cavalieri, singing some arias from Tosca reportedly with her own voice.

In her autumn years, her liaisons with younger men surfaced.

She was quoted to have said, “”A woman at 20 is like ice. At 30 she is warm. At 40 she is hot. We are going up as men are going down.”

Her last major film was in 1972 opposite David Niven in King, Queen, Knave. As showbiz accounts went,“there were tantrums on set and the production was halted three times for mysterious ‘eye problems’”.

Pursued by business tycoons, nominated in three Golden Globe awards and a Bafta (for Come September) but never made it, La Lollo was the star of the 50s and gradually faded into the late 60s.

In the 70s, she metamorphosed into a photojournalist and a sculptor.

She was a late bloomer politician who sought seats in the European parliament.

In the mid-70s while jetsetting with Cristina Ford and Van Cliburn, La Lollo met the most famous politician of them all, Imelda Romualdez Marcos.

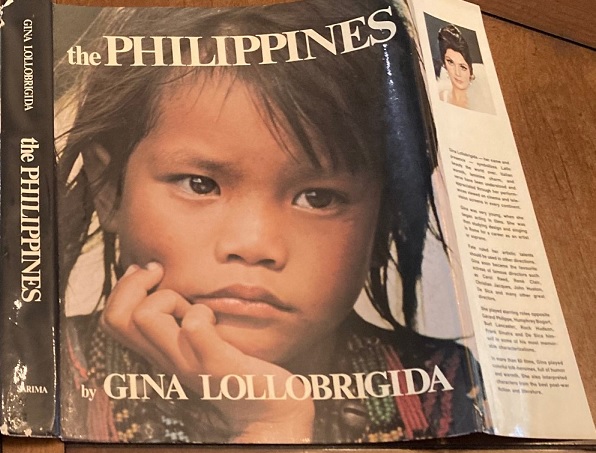

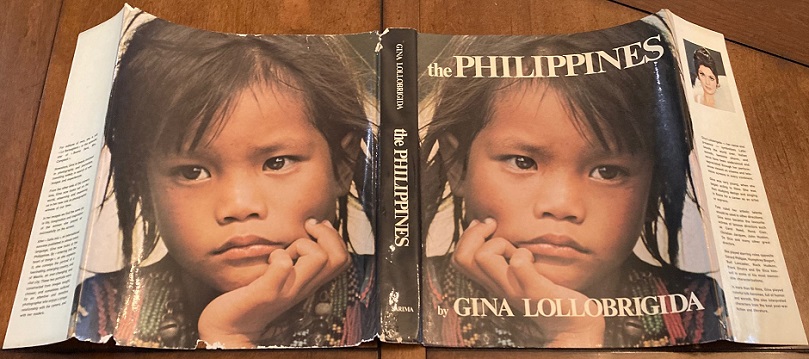

The former first lady got the Department of Tourism to commission the celebrated photographer to write two coffee table books – one on the Philippines and another one on Manila.

(It turned out the international sex symbol turned photojournalist was more interested in shooting the Tasadays as descendants of the Filipino race. They were falsely identified as “forest dwellers” and was supposed to have been discovered in the early 70s. It came too late in the day that the entire Tasaday story turned out to be pure hoax.)

In this episode called La Lollo in Manila in 1975, writer Carmen Guerrero Nakpil was assigned to do the book introduction.

In her book, Legends & Adventures, Nakpil wrote that the international sex symbol was able to wangle a “whale of a contract befitting her stature as the ‘sexiest woman alive.’”

The book contract was between the Italian sex symbol and the PNB represented by its president Panfilo Domingo.

Nakpil recounted her role was to provide the text and then travel to Italy to supervise the printing in Florence.

Nakpil recalled her first project meeting with Lollobrigida: “She had clearly seen better days, but she was still magnificently attractive, with huge, long-lashed eyes, a head of dark curls, the famous bosom and small waist.”

The writer noted the Filipino men present in the meeting were on the verge of a major crush.

As Nakpil showed her the text for the volumes on the Philippines and Manila, the Italian Hollywood star complained: the text did not seem to match her photos.

The writer gave the movie star a piece of her mind. “Your photos are all about a Stone Age tribe in the jungles of Mindanao, about half a dozen aborigines, and this book is supposed to be about 45 million Filipinos who don’t live in trees.”

The actress said her book has a different market and that Europeans are not interested in Filipinos living in high rise buildings and driving European cars on superhighways.

The writer insisted the book has to be truthfully told that Filipinos don’t live in caves.

The writer couldn’t hide her irritation on the project. “My irritation was aggravated by the dark freckles on Gina’s décolletage, the four sets of eyelashes she wore above and under each eye, and the wormy varicose veins on her legs visible only when she raised her long skirts. I refused to change a word of my text, ands it was not so much feminine envy as patriotic indignation. I was the librettist, the one who would supply the words for the operatic arias of her art photographs and that made us natural enemies. She had the imperiousness and arrogance of a Hollywood film star who expected adulation and subservience with one blink of her fantastic eyes and a pushy delivery that antagonized me with its comical Italian accent. I annoyed her because I remained unimpressed and was critical and argumentative, suspicious of her manipulative strategies.”

The writer and the celebrity photographer fought every time they met.

Indeed, the stage was set for a cultural battle commencing in Manila and ending in Florence where the books would have its final printing.

Nakpil’s concern: why was there too many photos of the Tasadays than for the ordinary Filipinos living outside the forest?

Observed Nakpil: “There was preponderance of people who were naked, with not even a G-string or a loincloth between them and the camera lens.”

Nakpil recounted the Italian pressmen suffered from cultural shock while insisting that the writer must have Spanish origin and insisting that real Filipinos have heights the equivalent of pygmies. The writer lost her patience and yelled at the Italian printers: “Who are you calling a pygmy?” looking down her nose. She knew it that the bias came from Lollobrigida’s photos of the Tasaday.

Meanwhile, the books on Manila and the Philippines carried the author’s unexpurgated text which dealt with the history, geography, economy and the character of the diverse Philippine population.

Lollobrigida got around to writing her own epilogue at the rear of the book.

Despite the lack of official approval, 60,000 copies of the books were copyrighted at Liechtenstein and printed by Zincografia Fiorentina in Italy in 1976.

Project overseer Marita Manuel also disapproved rushes for the proposed film project that would go with the books.

PNB withheld payment for Lollobrigida. PNB president Domingo argued that the books were not representative of the Philippines as stipulated in the contract.

As a counter action, Lollobrigida sued Mrs. Marcos who approved the book contract.

Domingo negotiated during the court hearing and the actress only got one tenth ($400,000) of the $4 million contract.

Books were delivered to Malacañang but never distributed. Mr. Domingo kept ten copies for his friends. Nakpil got a copy of her version “The Philippines” with front and back covers of the T’boli maiden in her hand-woven, beaded costume and a copy of “Manila” with Mrs. Marcos at the CCP entrance.

Lollobrigida’s Philippine photographic excursion using fake “forest dwellers” was the subject of a 2014 London exhibit of artist Pio Abad (nephew of another acclaimed visual artist Pacita Abad) called My Dear, There Are Always People Who Are Just A Little Faster, More Brilliant and More Aggressive.

The description of the exhibit says it all: “Abad uses the confluence of characters in this bizarre episode to reflect on the attempts of Imelda to create an image of civility during the onset of Martial law with the Tasaday and Lollobrigida fully encapsulating the absurd spectrum of characters made complicit in the weaving of this narrative. By transposing this narrative onto a silk scarf, Abad reconfigures this grand vision into a domestic one as he attempts to create what he calls ‘ergonomic representations’ of the complex network of political and artistic alliances, fraudulent ideologies and intimate, often petty, histories that have shaped our notion of Philippine modernity.”