The COVID-19 pandemic forced the government to borrow at the historic level of P3.2 trillion to manage the unprecedented health and economic crises that included providing stimulus packages for small businesses, unemployment benefits, incentives and financial assistance for health and other essential workers.

The national debt in 2021, a year after the pandemic hit, reached P11.72 trillion which was over half (60.4%) of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) or the total amount of products and services produced domestically over a particular period.

At the start of 2023, an international debt watcher reported that the Philippines is among the few countries that will see a decline in their debt stock “by several percentage points” based on projected high nominal GDP growth.

“But their debt burdens will still hover far above pre-pandemic levels,” Moody’s Investors Service, an integrated financial risk assessment firm based in the United States (U.S.), said on Jan. 9.

How much is the Philippines’ outstanding debt? Is it still manageable? What is the government doing to ease the debt burden? VERA Files Fact Check spoke with economists to break down the status of the country’s debt obligations:

1. How much is the Philippines’ debt?

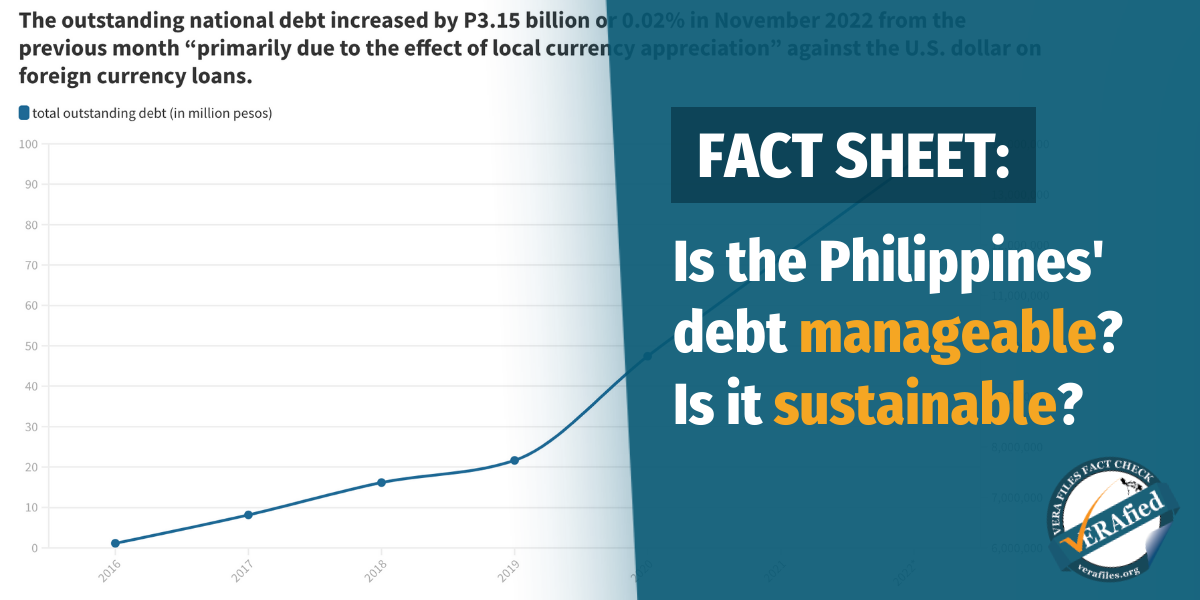

Because of the government’s pandemic-induced borrowing, the country’s total debt ballooned to a record high of P13.64 trillion from both domestic and foreign lenders as of November 2022, according to the Bureau of Treasury (BTr). This was up P3.15 billion or 0.02% from the previous month “primarily due to the effect of local currency appreciation” against the U.S. dollar on foreign currency loans. The peso fell by as much as 16.7% to an all-time low of P59 to $1 in October.

View this infographic that illustrates the Philippines’ debt profile:

With President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. enacting a P5.26-trillion budget for 2023, the government must borrow P2.207 trillion more to cover the projected budget deficit. This is broken down to P1.65 trillion from domestic sources and P553.5 billion from external sources.

2. Is the current debt manageable? Is it sustainable?

In December 2022, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) said that the country’s “debt burden remains manageable” compared with other countries like Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, Peru, and Mexico.

Data from the BTr show that the debt to GDP ratio of 63.7% last November was the highest in 17 years and is above the international threshold for debt sustainability of 60%.

Nicholas Mapa, senior economist at ING Bank, warned that the longer the debt-to-GDP ratio stays above this level, the more “susceptible” the Philippines will be to a credit rating downgrade “by at least one of the ratings agencies.”

A downgrade translates to higher borrowing costs and this could potentially have a “negative impact” on Filipino taxpayers as the government “may need to increase taxes to cover the increase in borrowing [f]or more expensive financing,” he explained.

Higher borrowing costs could also mean that debt levels “may be larger” or “government funding and support for its programs would be smaller” as money is diverted to pay for the interest on these loans. (See VERA FILES FACT CHECK: Marcos contradicts Diokno on giving ‘ayuda’ amid COVID-19 crisis)

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission defines credit rating as “an assessment of an entity’s ability to pay its financial obligations.” The BSP noted that the Philippines has a “strong credit profile” from at least three credit rating agencies: Moody’s, S&P Global, and Fitch Ratings.

3. What is the government doing to ease the debt burden?

Based on the enacted 2023 budget program, the government will pay P582.32 billion for interest payments and P28.7 billion for net lending.

This does not include the P1.01 trillion for principal amortization “as an expense item under any accounting standard” since it is “the settlement of debt obligations incurred from expenses already recorded in the past,” according to Finance Secretary Benjamin Diokno.

Apart from the automatic allocation for debt servicing in the budget, the Marcos economic team said it will prioritize boosting economic growth by 6.5% to 8% and target bringing down the debt-to-GDP ratio to 50% by 2028. The projection assumes a 2% to 4% inflation rate and foreign exchange rates at between P51 and P55.

“As long as the country stays united and its political leaders and policymakers remain focused on economic growth, the Philippines’ future remains bright,” Diokno wrote in a Dec. 28 statement declaring that the “worst is over” for the country and “better years are expected.”

Peña-Reyes stressed, however, that economic growth has to “outgrow debt” and “outpace inflation,” which reached a 14-year peak of 8.1% at the end of 2022. In reopening the economy, he said the government must consider the endemicity of COVID-19, the reopening of China, and potential peace between Russia and Ukraine which the National Economic Development Authority admitted were “headwinds” threatening the country’s economic growth.

“It’s a delicate balancing act. You cannot just really go rushing to pay off debts… If you allocate a huge chunk of your budget to debt servicing, what about the other services? You take away from those,” Reyes said.

Rene Ofreneo, president of Freedom from Debt Coalition, also noted “major, major problems in the economy, which can subvert the optimistic economic forecasts of the technocrats.” He cited “the terrible weaknesses in the efficiency of government operations as illustrated by the breakdown of the circuit breakers at the NAIA airport,” “the instability/disunity” within the military and the national police, and “the never-ending food/agricultural crisis as reflected in the onion crisis, salt crisis, sugar crisis, corn crisis, rice crisis and so on.”

“The whole point is that debt sustainability depends on the overall success in growing the economy. The government’s handling of the food-agricultural crisis does not inspire confidence that the country is on track to meet the 6-8% annual growth rate amidst a volatile and uncertain world economic order,” he said.