The 1986 political campaign of Cory Aquino was propelled by widespread indignation at the assassination of her husband, Ninoy, and the belief that a clique within the Marcos government had planned it.

Even the choice of yellow for the campaign was politically-rooted in Ninoy who never saw the ribbons in that bright color tied to trees when he returned to the country on August 21,1983 — the day he was brutally murdered in broad daylight before he could even step on Philippine soil.

This was the birth of the rain of yellow confetti along Ayala Avenue.

Cory’s campaign was the first of a wildly popular candidate waging a direct juggernaut against what was then an invincible dictator. Ferdinand Marcos Sr. had previously staged sham presidential elections in which paper opponents were paid to run against him in a charade.

In the February 1986 snap election he called, it was a coy widow who took up the challenge. That was not the dictator’s expectation.

A people robbed of their freedom was invigorated by the Ninoy prose that the Filipino was worth dying for. It became conventional consciousness. The Cory campaign was the first time a nationwide awareness emerged that it was very probable to vanquish the immense Marcos dictatorial might through the power of the ballot.

Images of public school teachers embracing ballot boxes with their bodies and tabulators of the Commission on Elections walking out of a publicly-recorded vote canvassing became political responses to a dictatorship that had all the cheating machinery in its hands.

The Leni Robredo-Kiko Pangilinan campaign is not just political but personal as well.

Last Wednesday, Leni returned to Negros Occidental to hold another rally. On her departure ride to the Talisay-Silay airport, her van took the route of the diversion road to the airport. A stationary caravan occupied the road’s shoulder for miles. Her van had to either slow down or stop several times to acknowledge the generous crowd who did not want to let her go.

Men and women shouted at the sight of her, some running to catch up with her van. “We love you, Mam,” “God bless you, Mam,” they called out. Some came with their entire families. Others brought their elderlies.

Leni’s van stopped to acknowledge one elderly woman in a wheelchair. A young man climbed a fence to catch a glimpse of her. A good number brought their pets. There were those who prepared send-off gifts to her. It was a family affair. This kind of very personal reaction seemed very unsettling because it had never happened before in Philippine electoral history.

What explains remote islanders from Agutaya, Palawan travelling 15 hours by boat just to see Leni in her Puerto Princesa rally? They wanted to thank her for introducing solar electricity, livelihood programs, and a feeding program for the public school children with stunted growth for lack of nutrition. But to do that by way of a 15-hour boat travel on rough seas?

How many Filipinos in the most remote villages and islands of our archipelago have ever cared that much for a presidential election that had always been decided by elite traditional politicians?

What explains realtor Gemma Pabayo Velasco of Cagayan de Oro allowing the use of her commercial building which she had painted totally pink and emblazoned with the name Balay ni Leni-Kiko? On the ground floor she assembled photos and artifacts to open a Leni-Kiko Museum for the public.

There were homemade placards too during the Cory rallies of 1986, but none so widespread and creative as this campaign. It was usually the political parties that had placards made for their candidates. Leni did not spend a single centavo for those that were displayed in her rallies. Many of the young, first-time voters immersed in social media, made the placards and composed the messages based on their fancy for hugot lines (hugot: to draw out emotions).

That Bacolod scene on the diversion road to the airport was replicated several times around the country when the people were tipped off about the route of Leni’s van. In another city, one man chased her ride, shouting in a hoarse voice through his face mask, “Mam, salamat sa pagmamahal mo sa bayan” (Thank you for your love of country). Still in another place, one man in tears held a tarpaulin and approached her van, saying to her “Ikaw na lang ang pag-asa naming” (You are our only hope).

Why are people taking this personally?

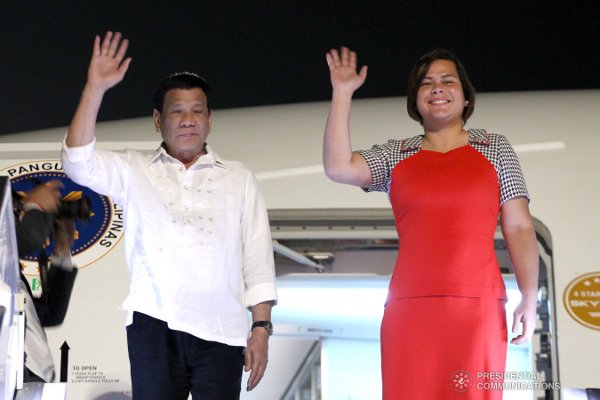

We elected Rodrigo Duterte in 2016 as a social experiment. We were made to believe that a petty provincial tyrant could change this country’s dirty politics. We did not see through the troll logic.

Duterte is as dirty as a trapo, as opportunistic as an oligarch, as false as his long litany of failed promises. He leaves us with trillions of pesos in debt. The country has become a colonial outpost of China. His cronies have been served with choice Comelec and telecommunications contracts. Classmates, Davao compatriots, and fraternity brothers got choice appointments in government.

And thousands lay dead in pauper’s graves from a drug war that Duterte never got to wipe out as he promised because it was simply designed to create the same terror he spread to silence the people of Davao City.

After six years, voters saw how the Duterte dynasty has been fattened with public lard. His children who have no scruples about hitting their critics even on public television only showed how they have inherited the canal-water mouth of their father (an angry friend invented that term).

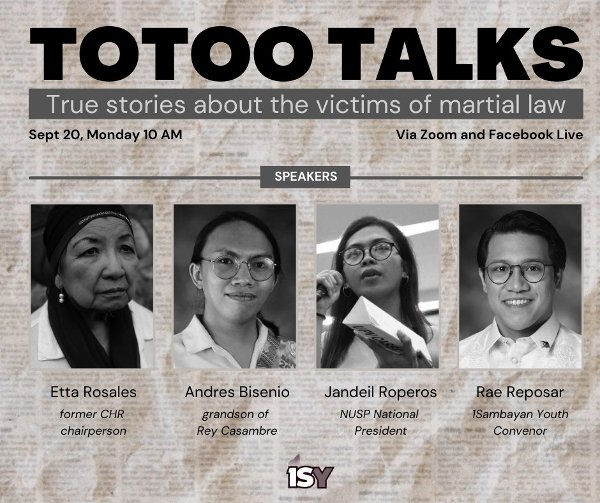

That is why vice presidential candidate Walden Bello, who had bluntly challenged Duterte’s daughter to a debate which she had evaded, was truly a bright highlight in this campaign. A non-trapo like Luke Espiritu rising for his boldness in cutting down to size Duterte-Marcos attack dog Larry Gadon was widely cheered.

A cousin decided to see for himself the Leni-Kiko rally on Macapagal Boulevard. He was floored by the zeal of volunteerism he saw. The people were happy, the mood festive. Food and friendships were readily offered. Showbiz stars came gratis et amore. By the time he left late that evening, my cousin was surprised even more: people continued to stream in droves and they were not bussed in or paid to attend.

That we are being inspired by Leni Robredo and taking to heart her advice to give radical love to those in the forgotten fringes of society; that we are seeing now the possibility that honest governance can be real; that it is achievable for public servants to serve without stealing from government, then we have raised the maturity of the Filipino voter, win or lose.

This has never happened before in history and it might never come our way again.

And lest we forget, this campaign has convinced many of us that the Marcoses stole big time, that martial law was never our golden years, that lying and faking and trolling are not the way to public service. We take this personally because we have become exhausted with politics of prevarication.

Leni Robredo and Kiko Pangilinan are Filipinos worth voting for.